Aaron Grade OUR ECOSYSTEMS

conservation environmental conservation nature environment sloss

Single Large or Several Small? The Ongoing Debate in Nature Preserve Design

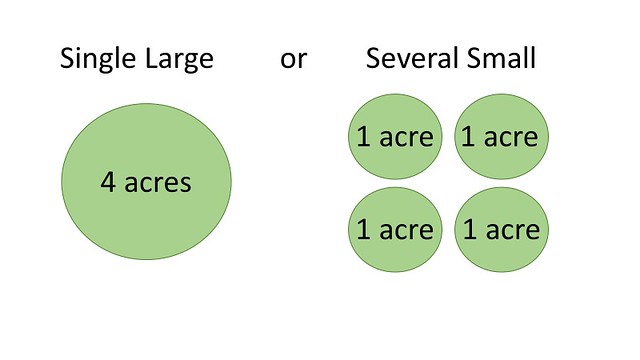

Imagine that you are a non-profit land trust manager tasked with preserving forests in and around town. You have come upon some money through a group of passionate donors who are interested in protecting the diverse species of forest birds in the area for future generations to enjoy. Where do you put these limited resources? Do you purchase one large tract of forest on the outskirts of town for a giant nature preserve? Or do you buy up a network of smaller patches of forest throughout town that add up to the same number of acres?

Fig. 1 Where would you prioritize your limited resources to best conserve town land such as this beautiful mountain forest in Amherst, Massachusetts. Image via Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mount_Norwottuck_in_Autumn.jpg

Conservation biologists have been struggling with this question since the founding of the discipline. Dubbed the “SLOSS” debate – for Single Large Or Several Small – this ongoing controversy has seen its fair share of passionate and persuasive arguments by both sides. I’ll present some of those arguments to you, an imaginary land manager, and I’ll let you decide what is best for your town:

Fig. 2 Which is better – Single large or several small?

Single Large

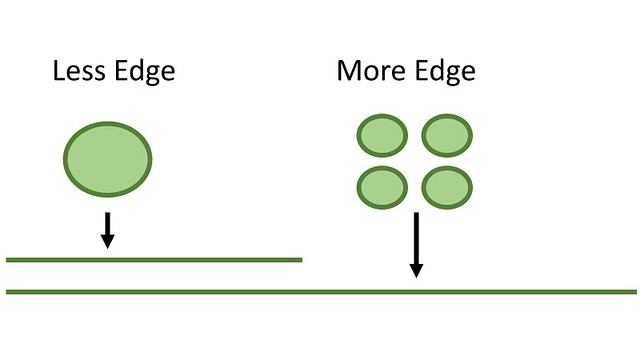

Clearly a single large nature preserve is always best! In simple mathematical terms, one large circle has less land exposed to the edge than four small ones of the same area.

Fig. 3 There is far more habitat exposed to “edge” with several small preserves.

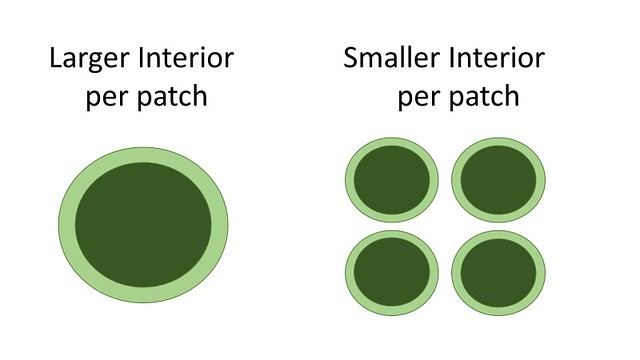

And, as I’ve written before, edge isn’t all that great for many species. Also, some species such as mountain lions need a large amount of space to persist. For other species, they prefer “interior” forested areas far from any edges. If you have small patches of forest, these species won’t even occupy the patch. To sum up, if you want to protect rare species, sensitive species, and apex predators such as mountain lions and wolves, you need a large preserve.

Fig. 4 Large preserves have more room for large animals to roam…although I’m pretty sure that Amherst doesn’t have mountain lions or wolves…

Several Small

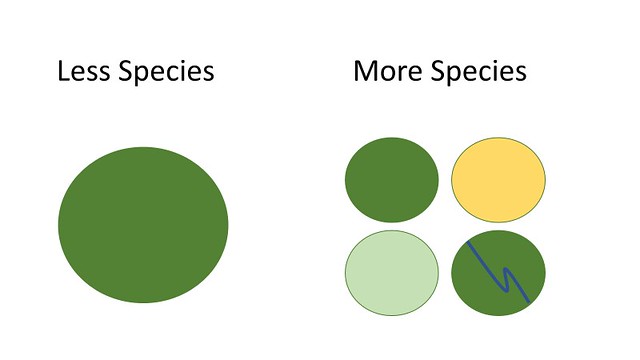

Not so fast, a single large nature preserve is NOT always best! Imagine the cost of buying a huge amount of land in Massachusetts. Is that acreage of land even available? There are some real benefits to having a network of small protected nature preserves. It may be easier to manage them. The land trust could use fencing around some sensitive properties, and designate others for walking trails. It’d be much harder to manage and protect a large tract of land. Also, if our goal is to maximize the number of species in town, several small preserves might be the way to go. If you preserve one giant tract of land, but it’s all the same kind of forest, you may have the same species throughout that one preserve. But if we buy up a variety of land, some meadows, some farms, some young forest, etc., we may end up getting more biodiversity overall.

Fig. 5 Large doesn’t always mean more species…check out this configuration with a diverse network or preserves of different land types.

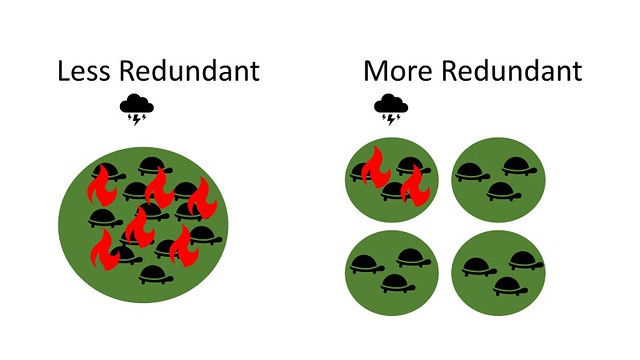

Some species may also be more protected from disturbances. Let’s pretend we have a population of a stick figure turtle species that we want to protect. If we put them all in one forest tract, a forest fire can wipe them all out! By spreading them between different patches of forest, they might be better protected from a disturbance like fire. The patches could also be strategically bought up to eventually connect to each other, creating a whole network of forest patches.

Fig. 6 No worries, let’s just put all the stick turtles right here in our preserve…Whoops.

Which would you choose?

These are real decisions that land managers must make every day. As you’ve probably gathered, there is no easy answer in this debate. In general, large nature preserves are always preferred over small ones, but it’s not always that simple. Some scientists also argue that if we prioritize large rural preserves over small urban ones, we isolate people from nature. When people are disconnected from nature and don’t experience it, they may not care as much about funding it. Having more green spaces in urban areas can lead to voters advocating for more environmentally friendly policies. That is the ultimate Catch 22 – isolate nature from people to protect it, just to end up with no political will in the future to protect it. Ongoing debates like SLOSS in conservation are ultimately useful ways for scientists and land managers to think through what is best for wildlife conservation, depending on the situation at hand.

Fig. 7 A more realistic Wood Turtle that we should protect from catching fire. Via Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WoodTurtle.jpg

References:

[1] Helmstedt, Kate J., Hugh P. Possingham, Karl EC Brennan, Jonathan R. Rhodes, and Michael Bode. “Cost‐efficient fenced reserves for conservation: single large or two small?.” Ecological Applications 24, no. 7 (2014): 1780-1792.

[2] Rösch, Verena, Teja Tscharntke, Christoph Scherber, and Péter Batáry. “Biodiversity conservation across taxa and landscapes requires many small as well as single large habitat fragments.” Oecologia 179, no. 1 (2015): 209-222.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- La Belle et La Boeuf (NOT!) How do human meat preferences impact climate change?

- Artificial Selection: From Tiny Fish to Empty Dish

- A breath of fresh air: How the great oxygenation event changed life on Earth forever

- The Women Behind the Gun vs. The Women Behind the Bird

- How Community-based Conservation Helps Lemurs

- More ›