Aaron Grade OUR ECOSYSTEMS

biodiversity conservation ecology human-wildlife interaction

Pleistocene Rewilding: A Controversial Idea in Conservation Biology

“You’re on a Land Cruiser full of tourists bumping along dirt roads across miles of rolling fields of tall grass. The brakes screech to a stop, and there’s a chaotic shuffle as everyone reaches for their cameras and leans out of the open windows. There they are! A herd of elephants and gazelles at a watering hole up ahead! And nearby in a patch of tall grass, a lioness stalks her prey…”

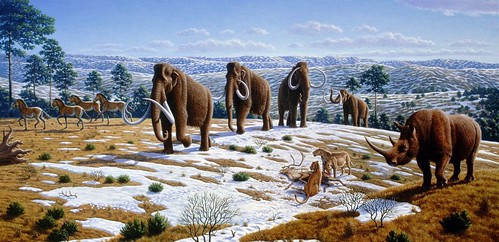

You are probably picturing this scene on the savannah of the Serengeti in Africa. Now what if I told you that a small community of conservationists want to transport this vision to the Great Plains of the U.S. [1]? Let’s dive into the controversial idea of Pleistocene rewilding and see what it could teach us about the field of conservation biology at large.

Fig. 1 - Imagine this same scene, but in Nebraska! (source:Wikimedia)

What is Pleistocene rewilding?

In conservation, rewilding is the act of restoring a location to its “original” ecological state by reintroducing the flora, fauna, and ultimately the ecosystem function that existed prior to human disturbance [1]. Rewilding advocates are especially interested in reintroducing megafauna, or large animals, that used to provide an important function to the ecosystem. For instance, large grazers allow for the persistence of grassland ecosystems since they browse on tree and shrub seedlings, not allowing them to get too large. A great example of rewilding is the restoration of bison and wolves to Yellowstone National Park. Bison and wolves were driven almost to extinction by overhunting. These species were deemed important for a healthy functioning ecosystem by managers of the park and were reintroduced back into Yellowstone [2].

Fig. 2 - Wolves and bison, both driven out of Yellowstone by humans, were reintroduced as an attempt to restore the ecosystem to its “natural” state. (source:Yellowstonegate.com)

A major philosophical question in rewilding is: How far back in history should we look for the “original” ecological state? In the case of Yellowstone, the park managers considered pre-western expansion (before 1800’s A.D.) as their time capsule; an era to aspire to. But clearly there were human influences on the environment way back into the Ice Age. In fact, it is widely believed by scientists that prehistoric peoples hunted much of the U.S. megafauna to extinction long before European colonists arrived. Back in the Pleistocene - also known as the Ice Age, which lasted from 2.6 million years ago to 12,000 years ago - animals that resembled modern day elephants, mammoths, cheetahs, giant sloths, lions, and even camels were a part of the “original” ecological state and performed important functions [3]. Take the Pronghorn; a species of antelope that currently roams the western U.S. The Pronghorn is capable of outrunning any living predator because it evolved to match the speed of the now extinct false-cheetah (Miracinonyx) [4]. Should “prior to 12,000 B.C.E.” be the era to aspire to? How to define the “original ecological state” remains a fiery debate in conservation biology.

Fig. 3 - False-cheetahs hunting pronghorns - A vision for bringing North America back to “the way it was” through rewilding. (source: Quora)

Pleistocene Park: Bringing them back from the dead?

Even if we agree that the original ecological state should resemble a pre-human ecosystem, restoring it may involve resurrecting extinct species such as the false-cheetah. De-extinction, or the ability to bring an extinct species back, is theoretically possible for some recently extinct species that have extant (living) close relatives. However, despite interesting advances in genetics, we are still not currently able to pull a “Jurassic Park” and bring long-lost species back from the dead. So for now it is safe to assume that de-extinctions at this scale are a distant dream.

The scientists that advocate for Pleistocene rewilding instead suggest the use of surrogate species, which are living species that are similar to extinct species. The thinking behind this is: (1) there is irrefutable evidence that we have disrupted Earth’s “natural state”, (2) large African megafauna populations are not doing too well anyway, (3) they resemble their long-lost American cousins close enough that releasing them into the wild in the U.S. could restore important ecosystem functions [5]. These released animals would, in effect, act as both surrogates of long lost species, and conservation breeding programs to restore populations of endangered African megafauna [1,5]. Imagine the benefits to the tourism industry in locations where these species would be released; it could be billed as a Pleistocene Park!

Fig. 4 Could we bring the mammoth and other species of extinct animals back from the dead? And should we? (source: Wikipedia)

Obviously, these ideas have been met with suspicion and even outrage from members of the public as well as members of the scientific community. There are huge implications to releasing what are basically invasive species, even in isolated areas. What if a lion eats a house pet, or worse? What would the economic impacts be when there are massive herds of grazers introduced to the Great Plains? Would the climate and habitats of the modern day support these species? All these challenges make this idea intriguing, but likely untenable.

Conservation biology as a values and mission-based science

The idea of Pleistocene Rewilding exists on the fringe of conservation biology, but the arguments surrounding it are a great example of how the field is different from most other fields of science. Conservation biology as a field must be values and mission-based. The very premise of conservation of nature requires that there is an agreed-upon target of which to “restore” an ecosystem. Is this target how the ecosystem used to function when we were children? When our grandparents were growing up? Before Western colonizers arrived? Before humans arrived? Since ecosystems are constantly changing regardless of human intervention, conservation biologists must weigh human values and competing goals. Is it important to have the original species in place, or is it fine to substitute surrogates that serve the same function, such as grazing? With a changing climate, is it even important to have the same ecosystem that was in place before, or is it more realistic to just have any functioning ecosystem that will provide “ecosystem services” to humans and animals alike? Most people would agree that humans have caused massive disturbances and extinctions, and that Earth’s biodiversity is valuable and must be protected. Moving forward, we all have a part in this debate. Do we want to get things back to the way they were? Would you advocate for a Pleistocene Park in the Great Plains of the U.S.?

Fig. 5 - Is this the future site of Pleistocene park? (source: USFWS via Flickr)

References

Josh Donlan, C., Joel Berger, Carl E. Bock, Jane H. Bock, David A. Burney, James A. Estes, Dave Foreman et al. “Pleistocene rewilding: an optimistic agenda for twenty-first century conservation.” The American Naturalist 168, no. 5 (2006): 660-681.

“Wolf Restoration.” National Parks Service. December 15, 2017. Accessed November 13, 2018. https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/wolf-restoration.htm.

Burdick, Alan. “Pleistocene Rewilding.” The New York Times Magazine. December 11, 2005. Accessed November 13, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/11/magazine/pleistocene-rewilding.html.

“Did False Cheetahs Give Pronghorn a Need for Speed?” National Geographic. January 08, 2013. Accessed November 13, 2018. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/phenomena/2013/01/08/did-false-cheetahs-give-pronghorn-a-need-for-speed/.

Donlan, Josh. “Re-wilding north America.” Nature 436, no. 7053 (2005): 913.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- La Belle et La Boeuf (NOT!) How do human meat preferences impact climate change?

- Artificial Selection: From Tiny Fish to Empty Dish

- A breath of fresh air: How the great oxygenation event changed life on Earth forever

- The Women Behind the Gun vs. The Women Behind the Bird

- How Community-based Conservation Helps Lemurs

- More ›