Grace Pold OUR ECOSYSTEMS

water soil ocean human fish environment conservation biodiversity agriculture

Mangroves: at your service

In a previous post, I mentioned that mangrove forests show a wide range of adaptations to the physically rough, salty, and low oxygen environment they inhabit. Despite this robustness, they are not immune to the kinds of extremes humans have caused.

Fifty years ago, mangrove forests covered 212,000 km2 [1]. Unfortunately, in the past 40 years mangroves have been lost at a rate of 1-8% per year [2], and 35% of all mangroves - an area equivalent to the whole of the Dominican Republic – was lost between 1980 and 2000 [3]. Development, aquaculture, and the lumber industry all have played a role in this.

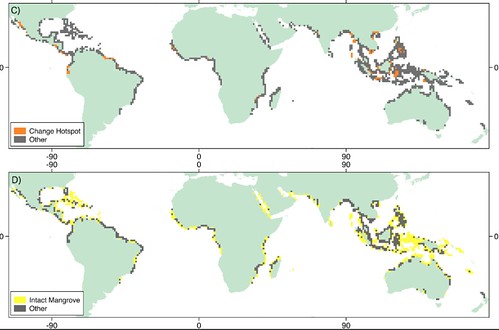

Figure 1: Global distribution of mangrove forests. Yellow areas in the bottom panel indicate intact mangrove ecosystems, while orange in the upper panel indicates areas where substantial changes in mangrove cover were detected by comparing satellite photos between 1996 and 2010. The remaining grey area indicates mangrove forests which have not undergone substantial losses over that same period. Modified from figure 2 in [5]

In places such as Florida, the desire to have a beautiful coastal view and ports large ships can pass into has fed the “draining and filling of the swamp” for decades now. Even by the 70’s, 20% or more of mangroves around cities had been lost [4,5]. While there has been some mangrove restoration in the southeastern US, efforts are patchy and mangroves and marshes continue to be illegally cut, pumped, dredged, and filled even as sea levels rise.

In contrast, the majority of mangrove losses in southeast Asia are driven by aquaculture, and in particular shrimp farming. Over the 9-year lifespan of a shrimp farm, a Vietnamese farmer can make $11,700/hectare profit, making it an attractive short-term option for indebted countries [5] but not for the environment.

Figure 2: Shrimp farming completely changes the landscape of the mangrove forests, converting them effectively into drainage ponds. Image from American Museum of Natural History.

However, this mangrove loss has devastating consequences for the health and wealth of humans and non-humans alike. Mangroves provide some of the best buffers between land and the ocean. Their maze of roots captures a lot of the sediment and high nutrient load from land, preventing it from reaching coral reefs which would otherwise be suffocated under it. The mangrove forest also works the other way too, dissipating the massive ocean forces before they reach the land. Indeed, loss of mangroves as a physical barrier was associated with a five-fold increase in economic losses and a 3-5% increase in human deaths following a cyclone [6]. Because of the confluence of nutrient capture and force dissipation, mangroves are also highly productive and serve as nurseries and spawning grounds for 10-75% of fish species [7]. Indeed, it is estimated that mangroves are worth $750-$16,750 per hectare to the fisheries industry [5].

Mangrove loss also has indirect effects on global health through their large carbon stocks. In converting mangroves into shrimp farms, 60% of the 600-1000 tons of carbon per acre is lost. This deforestation not only directly removes almost all the carbon as wood, it also prevents further removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and deposition as leaf litter and dead roots on and in the soil. Furthermore, the draw-down of water increases the amount of carbon loss from soil as both carbon dioxide and the 30-times more potent greenhouse gas methane [3]. All in all, this means that approximately half of the carbon footprint of your “surf-and-turf” dinner comes from the shrimp, with the same carbon footprint as driving halfway across the country [2]. Perhaps most devastatingly, the lifespan of a shrimp farm is rarely longer than 9 years because of disease and eutrophication, and by this point the soil is so degraded and the water patterns are so disrupted that the original, diverse mangrove you fell in love with will never be the same.

However, perhaps the most omnipresent influence of human activity is that of sea level rise. This is particularly noticeable in Florida, where a combination of highly regulated freshwater flows out from the Everglades, and large amounts of land only just above original sea level – have led to substantial inland retreat of these forests. As a part of the coastal colonization, large amounts of mangroves were removed and replaced with man-made sea walls, which the mangroves cannot retreat behind. It is thought that the mangroves stuck behind seawalls in southeast Florida will be completely drowned within 30 years [8]. This coincides with increased frequency and intensity of the very hurricanes these mangroves would otherwise protect humans from.

All is not lost, however. By helping mangroves move inland and ceding our current coastal territories to nature, we can increase the long-term ability of these beautiful, useful ecosystems to protect our inland investments elsewhere. Sometimes you just have to work with rather than against nature.

References:

Giri, Chandra, Edward Ochieng, Larry L. Tieszen, Zq Zhu, Ashbindu Singh, Tomas Loveland, Jeff Masek, and Norman Duke. “Status and distribution of mangrove forests of the world using earth observation satellite data.” Global Ecology and Biogeography 20, no. 1 (2011): 154-159.

Kauffman, J. Boone, Virni B. Arifanti, Humberto Hernández Trejo, Maria del Carmen Jesús García, Jennifer Norfolk, Miguel Cifuentes, Deddy Hadriyanto, and Daniel Murdiyarso. “The jumbo carbon footprint of a shrimp: carbon losses from mangrove deforestation.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 15, no. 4 (2017): 183-188.

Rosentreter, Judith A., Damien T. Maher, Dirk V. Erler, Rachel H. Murray, and Bradley D. Eyre. “Methane emissions partially offset “blue carbon” burial in mangroves.” Science advances 4, no. 6 (2018): eaao4985.

Teas, Howard J. “Ecology and restoration of mangrove shorelines in Florida.” Environmental Conservation 4, no. 1 (1977): 51-58.

Thomas, Nathan, Richard Lucas, Peter Bunting, Andrew Hardy, Ake Rosenqvist, and Marc Simard. “Distribution and drivers of global mangrove forest change, 1996–2010.” PloS one 12, no. 6 (2017): e0179302.

Barbier, Edward B. “Valuing the storm protection service of estuarine and coastal ecosystems.” Ecosystem Services 11 (2015): 32-38.

Sheaves, Marcus. “How many fish use mangroves? The 75% rule an ill‐defined and poorly validated concept.” Fish and Fisheries 18, no. 4 (2017): 778-789.

Meeder, John F., and W. Randall. Parkinson SE Saline Everglades Transgressive Sedimentation in Response to Historic Acceleration in Sea-Level Rise: A Viable Marker for the Base of the Anthropocene? Journal of Coastal Research 34, no 2 (2018):490 – 497.