Amy Strauss HOW IT WORKS

science and society health basic science golden fleece award golden goose award

Uncharted Intellectual Territory: Science Isn’t Linear

Science, by definition, is rooted in the idea of venturing beyond the limits of our knowledge into uncharted intellectual territory – asking questions without knowing the answers and making new discoveries through impartial observation and experimentation. Inherent in the nature of science is the unknown – it’s impossible for scientists to anticipate what new information will be uncovered through their work, or what future applications those discoveries might bring to human society. If scientists always anticipated the outcomes of their research and knew what they were going to find and how it might be used, the scientific process itself would be impaired.

Science has provided, and will continue to provide, the intellectual foundation for impactful technological, medical, industrial, environmental, and agricultural advances that fuel our nation’s progress and success. However, the path from initial scientific curiosity to impactful application in society is almost never a straight line. Such success often grows out of various ‘failed’ experiments, and almost always requires the synthesis of different independent research programs that may or may not have been working towards goals relevant to that particular outcome. If we trace back some of the modern tools and technologies that we rely on today (such as antibiotics, GPS, and Velcro), we can identify the numerous scientific discoveries that underlie these tools [8] – but predicting that connection in the opposite direction is often impossible.

Support for basic science research – research performed for the sake of improving our understanding of natural phenomena without a known application – is critical, because from countless examples, we see that innovation emerges in unexpected places [1]. For instance, the structural properties of mantis shrimp appendages have informed improvements in personal armor for the U.S. Military, and the soft hairs on gecko toepads that allow them to walk upside-down have inspired a reusable, glue-free adhesive used in manufacturing [2]. Unfortunately, basic research is not always heralded as a priority for government spending because of the indirect line from research to application. In fact, U.S. politicians have often ridiculed basic science research (i.e. hitting shrimp exoskeletons or looking at gecko toes) as an absurd waste of taxpayer dollars. As both a scientist and as a citizen, I find this concerning – but at the same time, I understand this view, particularly when public education around the scientific process is deficient. Taking a gamble on studies without direct, tangible utility, that may or may not spur societal progress, might not always seem prudent.

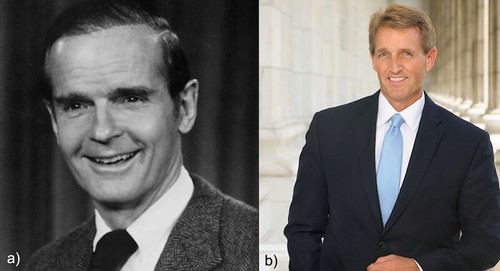

In the ’70s and ‘80s, Senator William Proxmire (Fig. 1a) was so infuriated by funding spent on research without an obvious application, he regularly targeted such studies in his ‘Golden Fleece Awards’, given to call out fiscally wasteful public officials. Included in the attacked scientific studies were many research projects using animal models, such as studies investigating jaw-clenching behavior and physiology in mammals or looking into the connections between alcohol and aggression in fish and rats [7]. Additional targets included an initiative to develop a six-legged robot, and funding to scan outer space for signs of extraterrestrial life [7]. Today, Senator Jeff Flake (Fig. 1b) similarly picks active, government-funded science studies to include in his ‘Wastebook’ to draw attention to their purported frivolousness. When attacking scientific studies, both senators have purposefully highlighted specific methodologies that seem bizarre out of context, without providing the bigger picture [1].

Fig. 1 – a) Senator William Proxmire (D) granted ‘Golden Fleece Awards’ in the 1970’s and 1980’s to highlight what he considered wasteful government spending, which often included federally-funded science research. (source: United States Senate Historical Office via Wikimedia Commons); b) Senator Jeff Flake (R) often attacks basic science research in his annual ‘Wastebook’, where he exposes examples of allegedly wasteful government spending. (source: United States Congress via Wikimedia Commons)

In 2016, Flake’s ‘Wastebook’ listed twenty federally-funded scientific research efforts he considered useless, and he gave them goofy-sounding nicknames such as, “Which has more hairs, a squirrel or a bumblebee?”, and “What makes goldfish feel sexy?” [5]. In response, the National Science Foundation (NSF) – the agency that funded these studies – provided clear, written explanations of: 1) their rigorous funding review process, 2) the broader context of each study, 3) any misconstrued/incorrect information from the ‘Wastebook,’ and 4) the scientific value (or intellectual merit, as the NSF calls it) of each study [9]. For the bumblebee example above (Fig. 2), they explain that there are tiny hairs around a bumblebee’s eyes that keep their eyes clean while foraging actively among flowers and collecting large amounts of pollen – understanding how these hairs work mechanistically may inform engineering applications such as keeping dust from lenses, sensors, and solar panels. For the goldfish study (Fig. 3), the NSF response explains that hormones such as testosterone can influence social behavior in animals. Goldfish were used as a model system to look at how behavior is influenced by steroid hormones in the brain, and findings from this study can be applied to humans due to the shared biology across species [9].

Fig. 2 – Bumblebees spend their time flying between flowers, collecting relatively large amounts of pollen all over their bodies – but their big eyes stay remarkably clean. How are bees able to avoid getting pollen in their eyes? (source: Beatriz Moisset via Wikimedia Commons)

Fig. 3 – Like other highly social vertebrates including humans, goldfish social behavior is mediated by steroid hormones acting in the brain. What mechanisms underlie hormone-driven behavior changes in goldfish, and what can that tell us about human behavior? (source: AlyssaChanPC via Wikimedia Commons)

In the early 2000s, Congressional Representative Jim Cooper (Fig. 4) was worried about how Proxmire’s fundamental misunderstanding and ridicule of science would influence the general public’s perception of science. He had the idea for an award to highlight federally-funded science research that contributed substantially to society and the economy. In 2012, the Golden Goose Awards were founded, celebrating unexpected major breakthroughs in medicine, technology, and other fields with important human applications. Awardees include: a wood chemist who developed a non-toxic wood glue inspired by ocean mussels that bind to wet, rugged surfaces [10], and two entomologists who used their knowledge of screwworm sexual behavior to develop ‘birth control for screwworms’ that successfully eradicated the very costly pest ravaging livestock nationwide [3].

Fig. 4 – Congressman Jim Cooper (D) inspired the Golden Goose Awards, which honor strange-sounding government-funded research that has led to unexpected breakthroughs benefitting society. (source: United States Congress via Wikimedia Commons)

Many unanticipated advances would be missed opportunities if we weren’t out there looking at the world around us. Of course, sometimes when looking, we don’t hit the scientific jackpot and we don’t uncover new insights. But those projects can help guide next steps, rule out possibilities, and generate ideas for new, creative research trajectories. And a critical component of this entire scientific endeavor is that we empower the general public with education around the process of science, to help US taxpayers understand the societal value of scientific exploration for the sake of scientific exploration.

As mechanical engineer and science communicator Dr. David Hu put it, “I hope my children can live in a world where scientists and the public are not at odds, but have a mutual understanding of the beauty and strangeness of nature, and how the pursuit of its oddities can lead to the benefit of all.” [6].

References

Brennan, P.L.R., Clark, R.W., and Mock, D.W. “Time to step up: defending basic science and animal behaviour.” *Animal Behaviour *94 (pp. 101-105), 28 Jun. 2014. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347214002334?via%3Dihub

Brennan, P.L.R., Irschick, D., Johnson, N., and Albertson, R.C. “Oddball Science: Why Studies of Unusual Evolutionary Phenomena Are Crucial.” Bioscience 64 (pp. 178-179), 1 Mar. 2014. https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/64/3/178/224831

Doucleff, M. “How the Screwworm’s Sex Life Saved Your Steaks.” NPR, 24 Jun. 2016. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2016/06/24/483259950/how-the-screwworms-sex-life-saved-your-steaks

Feder, E. and Minoff, A., hosts. “The Wastebook.” *Undiscovered, *WNYC, 13 Jun. 2017. https://www.wnycstudios.org/story/wastebook.

Flake, J. “Twenty Questions: government studies that will leave you scratching your head.” An Oversight Report, May 2016. https://www.flake.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2016/5/flake-releases-twenty-questions-government-studies-that-will-leave-you-scratching-your-head

Hu, David L. “Confessions of a Wasteful Scientist.” Scientific American, 25 May 2016. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/confessions-of-a-wasteful-scientist/

Irion, R. “What Proxmire’s Golden Fleece Did For – And To – Science.” The Scientist, 12 Dec. 1988. https://www.the-scientist.com/profession/what-proxmires-golden-fleece-did-for–and-to–science-62408

Jones, B. F. and Ahmadpoor, M. “Tracing the links between basic research and real-world applications.” The Conversation, 10 Aug. 2017. http://theconversation.com/tracing-the-links-between-basic-research-and-real-world-applications-82198

National Science Foundation. “Response to Senator Flake’s: “Twenty Questions: Government Studies that will Leave you Scratching your Head.” NSF Reports, 2016. https://www.nsf.gov/about/congress/reports/responsetosenflakestwentyquestions.pdf

Shivni, R. “How these 3 experiments went from goose egg to science gold.” PBS News Hour, 27 Sep. 2017. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/3-experiments-went-goose-egg-science-gold