Jake Barnett EARTH'S ORGANISMS

dna genomics sequencing

Who’s Got the Biggest Genome of Them All?

Genome sequencing is kind of a big deal. Every year more and more creatures get added to the list of fully sequenced genomes, and for as little as $600 [1] you can have your entire genome sequenced too! But what exactly is a genome? And how does the human genome stack up against the rest of Earth’s organisms?

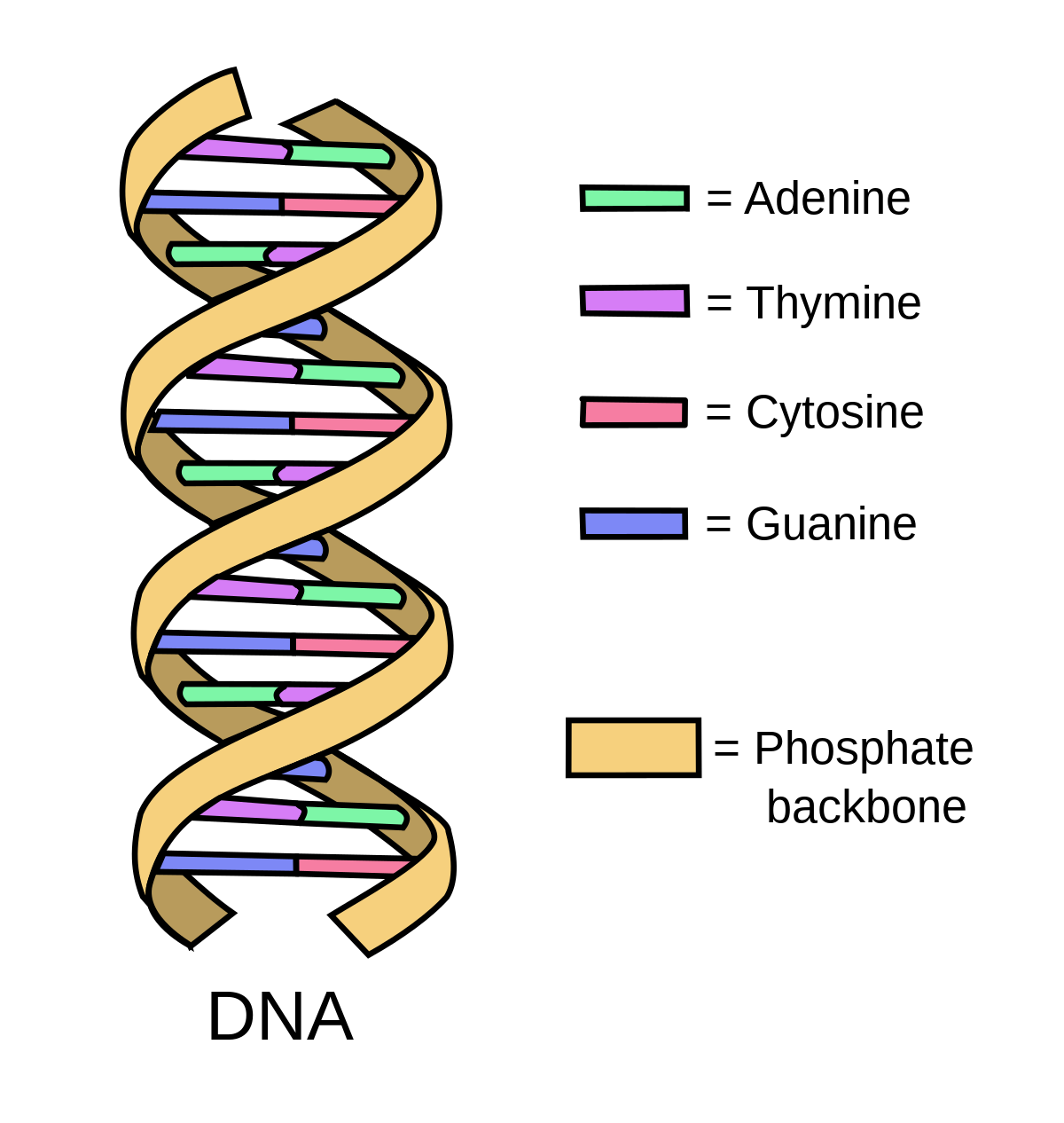

Inside the cells of every living thing we know about, you can find a remarkable chemical called DNA. This long, string-like molecule contains the instructions for how to build and control the organism. Believe it or not, only 4 chemical “letters”, or nucleotides, (A, T, C, and G) are used to spell out all this information in “words” of three letters each. An organism’s genome is simply a list of the exact order of every single letter in this DNA instruction code.

Figure 1. The “letters” of DNA. Photo source: Wikimedia commons by Forluvoft.

With only 4 different letters, this information this seems simple enough - until you realize that the human genome is about 3 billion letters long! That’s a lot of possible ways to arrange those 4 nucleotides. With the exception of identical twins, every human being has a slightly different order of letters in their genome. And just one single cell - a skin cell, let’s say - contains one copy of that entire genome.

3,000,000,000 is a lot of letters. If you consider that a typical 250 page book has about 500,000 letters, that means it would take 6,000 books to hold one person’s genome. But the human genome is nowhere close to the size of the biggest genome out there.

First, though, let’s zoom down to some of the smallest organisms we know - bacteria. A common and well studied bacterium, E. coli, has a genome of around 4,600,000 nucleotides [2] - only about 1/1,000th the length of the human genome. The smallest bacterium yet sequenced comes in at only 112,000 letters, and was discovered living inside of a tiny insect [3].

It makes sense that simple, microscopic life forms would have small genomes, but do genomes continue to get larger as creatures get bigger and more complex? Not necessarily - in fact the organism with the largest genome is probably not what you would expect. The record is currently held by a rare Japanese flower named Paris japonica, coming in at 149 billion nucleotides [4] - 50 times the size of the human genome!

Figure 2. Paris japonica, the rare Japanese flower that holds the current record for largest genome at 149 billion nucleotides. Photo source: Wikimedia commons.

How is it possible that a humble little flower can have so much DNA in one of its cells? There is more to a genome than just the total number of nucleotide letters. Not all of those letters actually give instructions to make something. In fact, only a fraction of a genome actually has the information for building the chemicals the cell needs. One “coding” region, known as a gene, holds the instructions for how to make one protein. Even though the human genome is 3 billion letters long, it only holds about 20,000 genes [5].

So in the case of the Japanese flower with the massive genome, much of that DNA is actually duplicate copies of the plant’s genes. More DNA does not necessarily mean more information - it’s sort of like having 100 copies of the same novel rather than having 100 different novels. These copies are not necessarily meaningless, however - gene duplication can lead to novelties and effects that scientists still working to understand.

Whether it is a tiny bacterium inside an insect or a towering spruce tree, every living thing we know of shares the same 4-letter instruction code. Humans fall in the middle of the pack in terms of genome size, but there is more to a genome than just the overall length. The part that actually gives unique instructions does not always match up with the total size.

While it is indeed a big deal, sequencing an entire genome is still just a first step. Figuring out what all those letters really mean is an even bigger task, and many discoveries have yet to be made inside the genomes of Earth’s organisms.

Table 1. Genome sizes of just a few of Earth’s organisms.

| Organism Type | Organism Name | Approximate Genome size, in number of nucleotides ("letters") | Number of protein-coding genes |

| Bacterium | Nasuia deltocephalinicola, a tiny bacterium that lives inside an insect [3] | 112,000 (0.112 million) * currently the smallest known bacterial genome | 137 |

| Bacterium | Escherichia coli [2] | 4,600,000 (4.6 million) | 5,000 |

| Plant | Arabidopsis thaliana | 135,000,000 (135 million) | 27,416 |

| Mammal | Homo sapiens, Humans | 3,000,000,000 (3 billion) | 20,000 [5] |

| Plant | Norway Spruce | 19,000,000,000 (19 billion) | 28,000 |

| Plant | Paris japonica, a rare Japanese flower [4] | 149,000,000,000 (149 billion) * currently the largest known genome | unknown |

References:

[3] Gordon M. Bennett, Nancy A. Moran. “Small, Smaller, Smallest: The Origins and Evolution of Ancient Dual Symbioses in a Phloem-Feeding Insect” Genome Biology and Evolution, Volume 5, Issue 9, 1 September 2013, Pages 1675–1688.

[4] Pennisi, Elizabeth. “ScienceShot: Biggest Genome Ever” Science, 7 October 2010.

[5] Ezkurdia, Iakes et al. “Multiple evidence strands suggest that there may be as few as 19,000 human protein-coding genes” Human molecular genetics vol. 23,22 (2014): 5866-78.

More about genomes and DNA from That’s Life [Science]:

Loder, Anthony. “DNA: Nature’s Hard Drive.” That’s Life [Science], January 16, 2017. http://thatslifesci.com/2017-01-16-DNA-Natures-Hard-Drive-ALoder/

More From Thats Life [Science]

- Freshwater Mussels are Declining: Why Should You Care, and What Can You Do?

- The Story of Chestnuts in North America: How a Forest Giant Disappeared from American Forests and Culture

- Friendships, Betrayals, and Reputations in the Animal Kingdom

- Why Don't Apes Have Tails?

- Giant Bacteria, Giant Genomes

- More ›