Rachel Bell EARTH'S ORGANISMS

biodiversity mammals birds

Things That Glow Pink in the Night: Why do some animals have fluorescent coloration under ultraviolet light?

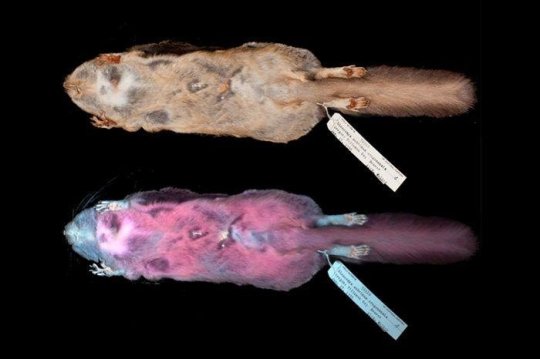

This past February, you might have seen articles pop up online about a startling new report in The Journal of Mammology: researchers found that when put under an ultraviolet light, multiple species of flying squirrels glow bright pink! Fluorescent pigment cells that glow bright and strange colors under ultraviolet light are actually pretty common in birds, who can see in the ultraviolet visual spectrum all the time [1]. However, this is the first recorded case of placental mammals having fluorescent coloration too [2]! After reading about these flying pink squirrels, I wanted to understand more about this natural phenomenon. So I dove into the bright pink, green, and yellow world of fluorescence.

Fig 1. The shockingly pink flying squirrels in question (Photo credit: Kohler et al. 2019).

The first thing I wanted to understand was the difference between the fluorescent coloration (or biofluorescence) we observe in birds, butterflies, and now flying squirrels, versus the bioluminescence seen in the hauntingly beautiful animals of the deep oceans. In the skin, scales, feathers, or fur of fluorescent animals, some pigment cells known as chromatophores contain fluorescent proteins. These fluorescent proteins are able to absorb light from the visible light spectrum, then immediately re-emit this light energy as wavelengths within the ultraviolet spectrum [3]. Interestingly, this is totally different from bioluminescent animals, who do not absorb and re-emit light but instead produce light within their cells via chemical reactions [4]! This difference also explains why we see biofluorescence in bright or low light conditions, whereas bioluminescence can happen in the pitch black darkness of deep oceans.

Fig 2. These animals are glowing through completely different biological mechanisms! The fish on the left (Photo credit: Sparks et al. 2014) are examples of biofluorescence, while the jelly on the right is an example of bioluminescence (Photo credit: uwe kils).

The second thing I wanted to know was why these animals from across the tree of life exhibit biofluorescence. Research on fluorescent pigmentation in birds shows that fluorescent patches or bands might be used to communicate with other birds. Specifically, these fluorescent colors seem to be frequently correlated with courtship displays and sexual signaling [5]. For example, the puffin’s fluorescent beak stripes are actually plates that form on the beak during breeding season [6]. These plates are shed afterward, suggesting they could be specifically linked to attracting mates [6]. Fluorescent colors might even be particularly adaptive for communication between birds because it stands out clearly from the background and may be invisible to most other non-avian predators [5]. In contrast, many species of spiders also fluoresce in bright colors visible to their insect prey and bird predators. Researchers think this might partially be because they background match with flowers that are also fluorescent [7]!

Fig 3. The amazing diversity of biofluorescent life! From left to right: A puffin specimen (Photo credit: Tony Diamond/British Trust for Ornithology); A scorpion, which is also an arachnid that exhibits fluorescent coloration (Photo credit: Jonbeebe); An ice plant with fluorescent flower buds (Photo credit: Craig P. Burrows).

When it comes to the bright pink flying squirrel, they are the first known case of fluorescence in placental mammals. The researchers who reported on their unusual coloration aren’t even sure yet if the flying squirrels are like birds and can see colors regularly in the ultraviolet spectrum. If the squirrels can see these colors, then the researchers posit the pink might be used in signaling and communication between squirrels! However, if squirrels (like most other mammals, including us) cannot regularly detect ultraviolet wavelengths, the scientists propose that this color may have emerged as a form of predator confusion: the owls who regularly hunt flying squirrels also glow pink under ultraviolet light, and might mistake the pink blur of a squirrel whooshing by for another owl [2]. No matter what the purpose of the squirrels’ pink fur is, this finding will hopefully make us scientists look for other mammals with biofluorescence that have yet gone undetected, hidden in plain sight.

References:

Giaimo, Cara. “Everything we know about birds that glow.” *Atlas Obscur*a (2018 April 11).

Kohler, Allison M., Erik R. Olson, Jonathan G. Martin, and Paula Spaeth Anich. “Ultraviolet fluorescence discovered in New World flying squirrels (Glaucomys).” *Journal of Mammalog*y 100, no. 1 (2019): 21-30.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- Freshwater Mussels are Declining: Why Should You Care, and What Can You Do?

- The Story of Chestnuts in North America: How a Forest Giant Disappeared from American Forests and Culture

- Friendships, Betrayals, and Reputations in the Animal Kingdom

- Why Don't Apes Have Tails?

- Giant Bacteria, Giant Genomes

- More ›