“Kate Otter” EARTH'S ORGANISMS

salamander massachusetts niche aquatic ecology orange

The Eastern Spotted Newt: A Wandering Teenage Identity Crisis

Teenage years. Ugh. If you’re anything like me you went through many stages in which your style, taste and attitudes changed dramatically. Maybe you didn’t rapidly switch between a purple mohawk and long brown hair, but most of us have experienced this searching phase.

Turns out this experience of wandering about and changing your looks and behavior between childhood and adulthood is not exclusive to humans. The eastern spotted newt, Notophthalmus viridescens, has a similar (though presumably angst free) stage of life.

Their life is comprised of four distinct phases. They begin as an egg, and like all amphibians these eggs need to be submerged in water to survive. In about 3-5 weeks, the eggs, which are laid in a thick protective gel underwater (Fig 1 [Top]), hatch into aquatic larvae with external gills (Fig 2 [Bottom]). These larvae feed on aquatic invertebrates and stay in the water for about 2-3 weeks [1].

Fig 1. [Top] An Eastern Spotted Newt egg mass from the bottom of a pond in Wendell, MA from April 2019 (source: Kate Otter). [Bottom] A larval Eastern Spotted Newt from Jennings County, IN (source: Andrew Hoffman, Indiana Herp Atlas https://www.inherpatlas.org/species/notophthalmus_viridescens).

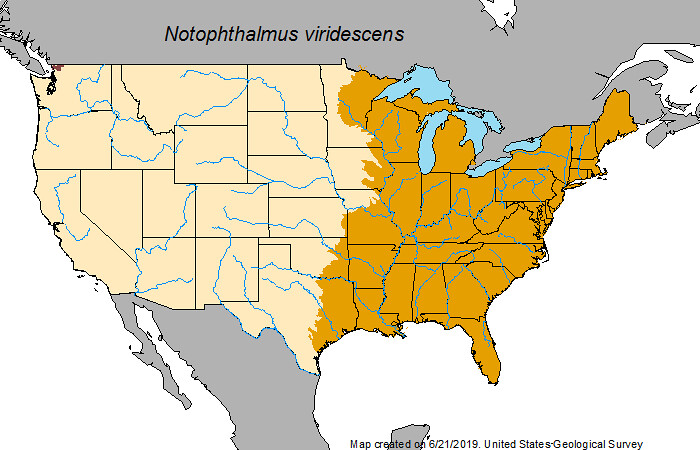

Now things get crazy. Whereas most amphibians would metamorphose into adults, these newts have an intermediate stage. Most of these newts will leave the water as a bright orange(see article on aposematism), toxic , terrestrial “eft” (Fig. 2)[1]. This eft- which is basically a “teenage” amphibian breathes with its lungs and develops a thick skin to avoid desiccation (drying out). These teenage newts roam up to 100m per day and eat terrestrial invertebrates [2]. Much like humans, it can take 3 to 7 years to grow out of this stage [2]. If you are anywhere in their home range (Fig. 3), you can see them traversing the forest floor after rains during the spring, summer, and fall.

Fig 2. Eastern spotted newt efts at the stage where you can see their bright orange coloration and rough skin, taken in May 2013 Harriman Park, NY (Source: Bruce Lucas via Wikimedia commons).

Fig 3. The dark orange on the map represents the range of *Notophthalmus viridescens *in the United States (Source: United States Geological Survey) [3].

After they have wandered to new bodies of water far from where they hatched, they will reinvent themselves and return to the water as sexually mature adults. Their skin dramatically changes color again, this time from a bright orange to an olive green with orange spots. Their tails widen and flatten, their skin becomes thinner, and they begin to hunt underwater as a keystone predator (predators that have a significant impact on their environment and in controlling prey populations) in many aquatic habitats [4].

Fig 4. An adult male Eastern Spotted Newt, where you can see the olive green delicate skin, orange spots, countershading (light belly and dark back) and wide flattened tail (Source: Brian Gratwicke via Wikimedia commons).

This life history is more complex than that of any other North American amphibian. Much like the varying environments of obligations and expectations that we humans must navigate as we grow into adults, these newts must be able to find food and survive in dramatically different environments. These metamorphic life events likely require changes in their brains and sensory systems as they need to be able to hunt in water, on land, and in water again. However, no one has studied the neuroscience of this double metamorphosis, and we likely have a lot more to learn about these curious creatures.

Exploring different niches (roles in an environment) can be a normal part of your life history. Choosing whether to blend in or stand out can be a natural part of life (Fig. 5). Hopefully as you meet life’s changes and have to redefine who you are, you’ll remember that you’re not alone. There are newts all over the United States trying to figure this out too.

Fig 5. (Left) An Eastern Spotted Newt eft on the forest floor in Gosham, MA where you can see that their orange coloration is not for camouflage but is a warning for predators that they are toxic, taken in September 2019 (source: Nikki Lee via personal communication). (Right) Two eastern spotted newts after mating in a pond, taken in April 2019 in Wendell, MA where you can see how their olive green coloration and countershading blends in with the pond (source: Kate Otter).

References

Gibbs, J. P. et al. Salamanders: Species Accounts. in The amphibians and reptiles of new york state : Identification, natural history, and conservation 49–106 (Oxford University Press, 2007).

Roe, A. W. & Grayson, K. L. Terrestrial Movements and Habitat Use of Juvenile and Emigrating Adult Eastern Red-Spotted Newts, Notophthalmus Viridescens. Journal of Herpetology 42, (2008): 22–30.

Procopio, Justin, 2019, Notophthalmus viridescens (Rafinesque, 1820): U.S. Geological Survey, Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL, https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?speciesID=3251, Revision Date: 8/15/2019, Access Date: 9/12/2019

Smith, K. G. Keystone predators (eastern newts, Notophthalmus viridescens) reduce the impacts of an aquatic invasive species. Oecologia 148, (2006): 342–349.