Lian Guo EARTH'S ORGANISMS

fish fishing barotrauma adaptation ocean

The Drama of Barotrauma: Blobfish, Rockfish, and More

Blobfish rose quickly to internet fame for its sad, saggy, mucousy looking face (Fig 1). It has made its way around the world in memes, stuffed animals, and even featured in Saturday Night Live. What you might not know is that blobfish, formally known as blob sculpin (Psychrolutes phrictus), does not look like a blobfish, at least not 9,200 feet (1.7 mi) below the surface of the ocean [1]. Have a look for yourself (Fig. 2)!

Figure 1. A blobfish at sea level is not so appetizing… (Source: kinskarije)

Figure 2. Footage from the E/V Nautilus of alive blob sculpins (aka blobfish), looking a little less like yesterday’s jello. (Source: E/V Nautilus)

So what happened to blobfish? Barotrauma! This term refers to physical trauma caused to an organism from rapidly changing environmental pressure levels. At sea level, earth’s atmosphere exerts 14.6 pounds of pressure per square inch (psi) of your body’s surface. This amount of pressure is called an atmosphere (atm). Every ~112 feet you descend into the ocean, there is one additional atm of pressure acting on your body. If you’ve ever swam to the bottom of a pool, you can already feel extra pressure on your head and ears. Now imagine what the pressure must be like seven miles below sea surface, at the bottom of the Mariana Trench; the pressure would be eight TONS psi [2]! This presents an incredible challenge to life in the ocean, because the deeper you go, the more pressure your body and all its parts (lungs, cells, proteins!) must withstand.

This incredible stressor has driven the evolution of adaptations in fishes and other deep-sea organisms. Deep in the ocean, a protein from a land animal would be deformed as water under high pressure is pushed to the center of the protein [2]. Proteins are often called the workhorses of the cell; these molecules have a particular shape which allows them to bind to and modify other molecules. If a protein cannot keep its shape or bind to its target, it cannot perform its function! One example of a deep-sea adaptation is the use of small organic molecules, like trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), to allow proteins to their job normally. TMAO works by binding to water molecules, preventing water from being forced into protein structures and providing more room in the cell for proteins to do their job. The utility of TMAO became clear when scientists found that the amount of TMAO in fish increases with depth!

However, it is thought that there is a biochemical limit for the use of adaptations like TMAO at ~5.1 mi deep [3]. At this depth, the amount of salt that naturally accumulates with TMAO in cells is similar to that of seawater; if any more TMAO and therefore salt enters fish cells, seawater will begin to rush into cells to balance the concentrations of salt. This is bad for cells. Imagine filling a water balloon - if you add water to it rapidly, it will reach a breaking point and burst. Burst cells are not good, at least if you want to stay alive! So far, this hypothesis of a biochemical limit in deep-sea fish still stands. The deepest fish ever found, a snailfish, was just over 5 miles deep in the Mariana Trench (Fig. 3) [3].

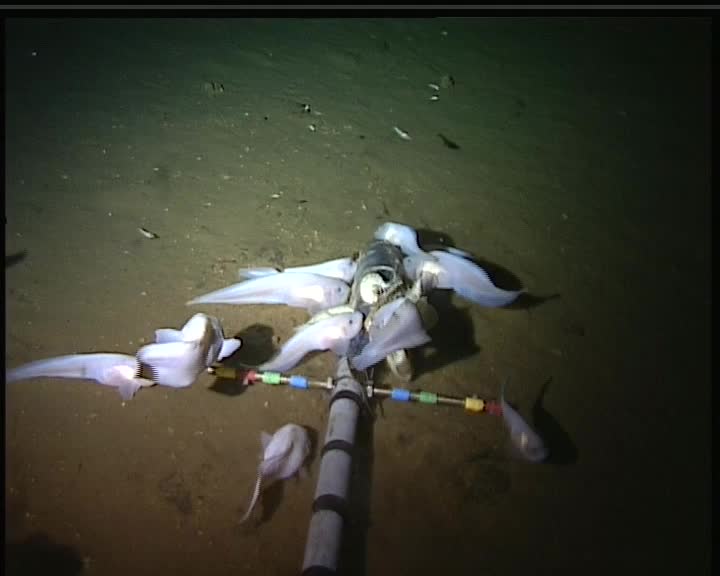

Figure 3. Footage of the (known) deepest-living fish in the world – snailfish from the Mariana Trench. (Source: SOI/HADES/University of Aberdeen, Dr. Alan Jamieson)

This is just one example of how fish have evolved to thrive under great water pressure. Now, when deepwater fish are brought rapidly to the surface, it causes their body parts, which are acclimated to high pressure, to expand. The most obvious example is in rockfish species. Rockfish live on or near the bottom of the ocean. When they are caught and brought rapidly to the surface, their stomach pops out of their mouth like a balloon and their eyes bulge out of their head (Fig. 4). It makes for a clownish appearance, but in fact this is a fish experiencing severe barotrauma! What is even more incredible is that these fish ARE NOT DEAD!

Figure 4. A yelloweye rockfish experiencing barotrauma, see bulging eyes and inverted esophagus. (Source: Oregon State University)

Many rockfish species are threatened and therefore fishers are not allowed to keep many of them. However, if the fish now have a balloon for an esophagus, upon being released they will not be able to swim to a depth that would allow them to recompress, at least not before a bird or other predator picks them off. This has led to high mortality rates for rockfish who are accidentally caught by fishers, even though many fishers tried to return the fish to the water. Initially, people would try to solve the “balloon” issue by pricking the inflated esophagus with a knife or needle. While this did deflate the esophagus, most fishers did not take the time to sterilize their pricking tools and fish would still die from infections. A solution that has been implemented with great success is to use a descender device (Fig. 5), which attaches to a fishing rod with a weight. The device allows you to drop the fish back down to depths where the fish can recompress and swim away. See the magic for yourself! Fish balloon -> fish!

Figure 5. Several ways to help rockfish with barotrauma descend to their deepwater homes, alive and safe! (Source: UCSC Rockfish Barotrauma Project)

The next time you see blobfish looking sad and grumpy, you now know why it looks that way. It’s just dealt with some serious baro-drama.

References:

[1] Keartes, Sarah. “Blobfish Might Be a Gooey Mess out of Water, but Check out a Living One! (VIDEO).” Earth Touch News Network, 25 Sept. 2019,

[2] Fox-Skelly, Jasmin. “What Does It Take to Live at the Bottom of the Ocean?” BBC, BBC, 29 Jan. 2015, www.bbc.com/earth/story/20150129-life-at-the-bottom-of-the-ocean.

[3] Yancey, Paul H., et al. “Marine fish may be biochemically constrained from inhabiting the deepest ocean depths.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111.12 (2014): 4461-4465.