Guest Writer EARTH'S ORGANISMS

nature conservation forest climate change apes frugivores

How Monkeys and Apes Fight Climate Change by Eating Fruit

by Stephanie Smith - Winner of the 2020 TLS Writing Contest

Frugivorous primates are keystone species that aid in forest regeneration through their role as seed dispersers.

Many primates are frugivorous, meaning their diet primarily consists of fruits. Though they aren’t aware of it, all of this fruit-eating can have a massive beneficial impact on their habitat! These frugivorous primates play crucial roles as seed dispersers for a broad range of trees, so much so that they are considered “keystone species” [9]. Keystone species are those that have large effects on their surrounding environment due to the vital role they play in the community; they positively influence the species diversity of an ecological community [1]. Seed dispersing frugivorous primates promote the growth of forest trees, which function as carbon sinks. Monkeys and apes disperse the highest quantity of seeds compared to other seed dispersers in the same habitat [6]. Therefore, primates play active roles in allowing the continuation of the carbon cycle and carbon sequestration against global climate change. Let’s explore this process in more detail!

Figure 1 Tropical forest squirrel monkey eating a fruit. Source: Tambako The Jaguar

What is seed dispersal? Why is it important?

Seed dispersal is an essential ecological process in which the seeds of a parent tree are taken to another area by an animal or the wind. With less competition, the seeds can flourish and grow. Seeds are then deposited in favorable areas for germination of various tree species. This important ecological process increases tree gene flow and spurs the restoration of tropical forests [9], allowing forests to grow. Monkeys and apes are seed dispersers, and as such are integral for maintaining a balanced ecosystem by influencing ecological forest regeneration.

Frugivorous primates consume fruits and disperse the seeds in one of two ways, depending on their dietary adaptations and ecological feeding behaviors. Typical fruits consumed by monkeys and apes are fleshy or have a thick outside rind, juicy pulp, and a single large seed [8]. The two ways in which primates can be successful seed dispersers are

eating the fruit and spitting out the seeds and

consuming the whole fruit and defecating the seeds [10].

Old World cercopithecine monkeys that have cheek pouches, such as baboons, mangabeys, and macaques, will store a lot of fruit in their cheek pouches and retreat to a secondary location to consume the fruit, then spit out the seeds. The fleshy fruit is stripped from the seed and eaten by the primates, while the seeds are either spat out or dropped [5]. However, other primates including spider monkeys, howler monkeys, and chimpanzees consume the fruit and defecate complete seeds. After stripping the pulp and swallowing the seeds whole, these primates transport the seeds in their gut and defecate complete seeds a great distance away from the parent tree, hours to days after eating the fruit [10]. Here the seeds experience little to no competition with the parent tree and have increased germination rates [5].

Not only do they disperse a greater diversity of seeds compared to other animals [6], but the seeds consumed and dispersed by primates have a higher germination success rate than those deposited close to the parent tree [5].

The most successful seed-dispersing primates are those who have a mainly frugivorous diet and have larger body sizes such as howler monkeys, spider monkeys, chimpanzees, and gibbons, since they consume a wide range of fruits in high quantities [6]. Larger-bodied frugivorous monkeys and apes are the main consumers of large seeded fruits in tropical rainforests compared to other, smaller-sized seed dispersing animals [6]. Their larger body size means they can eat fruits with large seeds that other small frugivorous animals can’t swallow.

Figure 2 Howler monkey biting into a fleshy fruit. Photo Credit: Ron Gallagher

Carbon sequestration

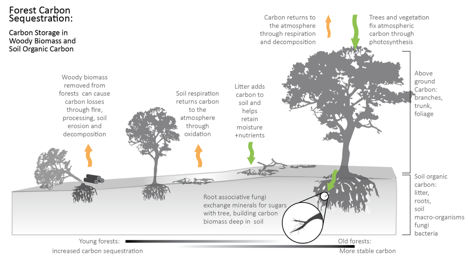

Large-bodied primates are the primary disperser for large-seeded tree species and hold an active role in the sequestration of carbon [11, 3]. Carbon storage is the process by which forests and trees absorb and regulate carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, which helps to mitigate the effects of global climate change [4].

Compared to trees with smaller seeds, large seeded tree species have higher carbon densities, meaning these species of trees are better at maintaining carbon storage and serve as an reservoir to diminish the effects of increased carbon emissions [11]. Tropical rainforests store large quantities of carbon with primates as the predominant animal dispersers for carbon-rich trees—those that store more carbon per unit volume—due to their higher wood density [2]. Therefore, preserving primate populations to allow the continuation of seed dispersal directly correlates with the sequestration of additional carbon in tropical rainforests and mitigation against climate change [2, 11].

Unfortunately, the rate of carbon absorption by trees is declining due to anthropogenic effects and increasingly altered ecosystems [7]. Research presented by Daniel E. Bunker, which studied the loss of over 200 tropical tree species in a 50-hectare plot in Panama, highlights a forest’s ability to sequester carbon and its risk due to the current changes in species composition. The researcher remarks that current anthropogenic influence in tropical rainforests and loss of biodiversity will result in future declines of carbon sequestration [4].

Figure 3. The process by which forests and trees sequester carbon dioxide (CO2). Trees and vegetation absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store the chemical for hundreds of years as a means to reduce the atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide. Source: Board of Water and Soil Agency

In tropical rainforests, the continued loss of primates has resulted in negative changes in the genetic diversity and distribution of tree species, which have cascading effects on trees and animal communities within the ecosystem [11]. Tree species that depend on primates for dispersal— those whose seeds are too large to be spread by other, smaller animals [2]—are declining [4]. These larger-seeded tree species have higher carbon densities compared to smaller-seeded tree species [11] and the loss of primates to facilitate seed dispersal results in the declining biodiversity of tropical rainforests, specifically the decrease in forest carbon storage of trees by approximately 5.8% on average [11, 2, 4]

Now more than ever, maintaining wildlife populations that encourage ecological processes is necessary and important when considering the conservation of habitat and ecosystem diversity [9]. Understanding these issues is the first step in making informed decisions and creating appropriate conservation methods that preserve and support not only primates species, but forest biodiversity in the long term.

References

[1] Bowman, W. D., Hacker, S. D., & Cain, M. L. (2017). Ecology. Sinauer Associates.

[2] Brodie, J. F. (2016). How Monkeys Sequester Carbon. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 31(6), 414-416. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2016.03.019

[3] Bufalo, F. S., Galetti, M., & Culot, L. (2016). Seed Dispersal by Primates and Implications for the Conservation of a Biodiversity Hotspot, the Atlantic Forest of South America. International Journal of Primatology, 37(3), 333-349. doi:10.1007/s10764-016-9903-3

[4] Bunker, D. E. (2005). Species Loss and Aboveground Carbon Storage in a Tropical Forest. Science, 310(5750), 1029-1031. doi:10.1126/science.1117682

[5] Chapman, C. A. (2005). Primate seed dispersal: Coevolution and conservation implications. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 4(3), 74-82. doi:10.1002/evan.1360040303

[6] Corlett, R. T. (2017). Frugivory and seed dispersal by vertebrates in tropical and subtropical Asia: An update. Global Ecology and Conservation, 11, 1-22. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2017.04.007

[7] Joyce, L. A. (n.d.). Menu. Retrieved from https://nca2014.globalchange.gov/node/5703

[8] Mcconkey, K. R. (2009). The Seed Dispersal Niche of Gibbons in Bornean Dipterocarp Forests. The Gibbons, 189-207. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-88604-6_10

[9] Sengupta, A., Mcconkey, K. R., & Radhakrishna, S. (2015). Primates, Provisioning and Plants: Impacts of Human Cultural Behaviours on Primate Ecological Functions. Plos One, 10(11). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0140961

[10] Traveset, Anna. (1998) Effect of seed passage through vertebrate frugivores’ guts on germination: a review. *Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics. *https://doi.org/10.1078/1433-8319-00057

[11] Wich, S. A., & Marshall, A. J. (2016). An introduction to primate conservation. An Introduction to Primate Conservation, 1-12. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198703389.003.0001

More From Thats Life [Science]

- Freshwater Mussels are Declining: Why Should You Care, and What Can You Do?

- The Story of Chestnuts in North America: How a Forest Giant Disappeared from American Forests and Culture

- Friendships, Betrayals, and Reputations in the Animal Kingdom

- Why Don't Apes Have Tails?

- Giant Bacteria, Giant Genomes

- More ›