Rachel Bell EARTH'S ORGANISMS

virus microbiology ecosystem amoeba

What's the world's largest virus?

Viruses are a major component of earth’s ecosystems and exist in nearly every corner of the world. Though some—such as coronaviruses, lentiviruses, and rotaviruses—parasitize animal hosts, plenty of viruses exist in our ecosystems that cannot harm us. Some viruses specifically infect and replicate within bacteria, and are called bacteriophages. Others target single-celled organisms known broadly as amoebas. Extraordinarily, these amoeba-targeting viruses include the largest viruses in the world. Not only are these viruses remarkable for their size: their complexity has completely shifted how scientists think about the origin of viruses and life on Earth. But first things first, what are the biggest viruses in the world?

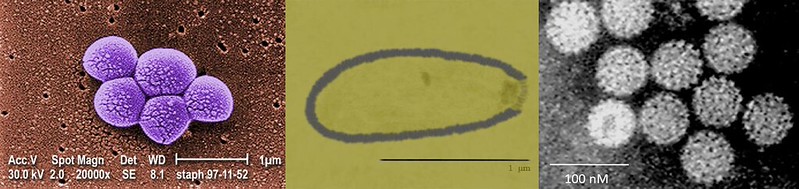

Figure 1. A reconstructed computer image of a rotavirus particle, which can infect humans and cause gastrointestinal distress. Its external structure allows it to attach to and infect cells. Image credits: Graham Colm via Wikimedia Commons

There are actually two different candidates for largest virus in the world, depending on how we define “giant!” The most straightforward definition is physical size. Most viruses are 20-400 nanometers in diameter [1]. The physically largest virus is Pithovirus sibericum, at 1.5 microns (or 1,500 nanometers) in length [2]. Though that might seem tiny, it is larger than some bacteria, and approximately half the width of a strand of spider web silk [3]. Pithovirus sibericum was discovered in 2014 in a sample of 30,000 year old Siberian permafrost, and was able to infect amoebas in laboratory settings despite its age [2]. Unlike typical viruses, these giant viruses are large enough to be seen using light microscopy—which is a way of looking at microscopic organisms that uses visible light wavelengths [4]. Most viruses are actually smaller than the shortest wavelength of light, meaning they cannot be observed with visible light no matter how much you magnify them [5]! Giant viruses are an exception.

Figure 2. A comparison of bacteria and viruses, all with scale bars. From left to right: MRSA bacteria with a scale bar of 1 micron; the largest known virus Pithovirus sibericum with a scale bar of 1 micron; HPV particles with a scale bar of 100 nanometers (equal to 0.1 microns!). This figure illustrates how Pithovirus is closer in size to many bacteria than it is to other typical viruses like HPV. Image credits (from left to right): Janice Haney Carr via the Public Health Image Library, Pavel Hrdlička via Wikimedia Commons, Dr. Graham Beards via Wikimedia Commons

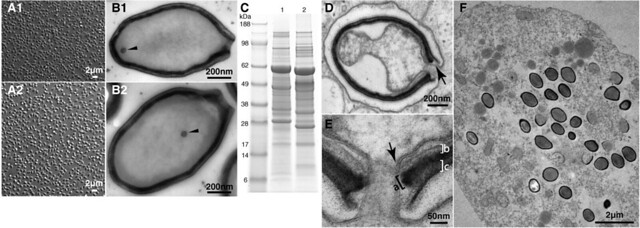

Another candidate for the world’s largest virus is the virus with the biggest genome (the entirety of its genetic material). For some context, one of the smallest viral genomes is around 5,000 base pairs in length [6]. Pandoravirus salinus is a giant virus with a genome approximately 2.5 million base pairs in length [7]. That is larger than many bacterial genomes and even bigger than the genome of a type of microscopic fungi [7,8]! Pandoravirus salinus was found in the marine sediment layer off the coast of Chile, and similarly parasitizes aquatic amoebas [7].

Figure 3. Pandoravirus salinus and Pandoravirus dulcis particles within host cells. Figure from Philippe et al. 2013

These are only a couple of the many giant viruses described over the past decade. Giant viruses are unlike any other organism or virus around today. They exist all over the world, from marine and freshwater ecosystems to permafrost to forest soils, and all generally parasitize amoebas [2,7,9,10]. Why exactly are these viruses so much bigger than others? Viruses are not considered living cells like bacteria or other microscopic organisms. Before we knew about super-giant viruses, the hypothesized ancestor of all viruses was miniscule [10]. More complex viruses were thought to have “stolen” genes and functions over time from the cells they parasitized [10]. Giant viruses poked a hole in this model: they resemble cells in genomic complexity and size, but most of their genes don’t resemble anything found in microscopic organisms [2,7], so it is unlikely they “stole” them. A new explanation for viral diversity had to be found.

The discovery of giant viruses strengthened the idea that viruses developed through the loss of genes and functions over time from a larger ancestor [10]. In fact, viruses may have originated from ancient protocell lineages that existed before the last universal common ancestor of all life on earth [10]. As these protocell lineages began to parasitize others, perhaps they did not need as many genes and functions to replicate as they began to rely more and more on the functions of the cells they infected [10]. These various lineages of parasitizing protocells may have given way to viruses. Though most viral lineages have lost many of their genes and functions over time, giant viruses lost comparatively fewer and may more closely resemble the ancient protocells from which they came [10]. There is still much to be learned about giant virus diversity, but the little we know about them has already provided new interpretations of viral origins and the development of life as we know it.

References:

[1] Virus Size and Shape. Encyclopædia Britannica. Accessed July 21 2020.

[2] Legendre, Matthieu, Julia Bartoli, Lyubov Shmakova, Sandra Jeudy, Karine Labadie, Annie Adrait, Magali Lescot et al. “Thirty-thousand-year-old distant relative of giant icosahedral DNA viruses with a pandoravirus morphology.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, no. 11 (2014): 4274-4279.

[3] Ramel, Gordon. Spider Silk 101: What’s It Made Of And How Strong Is It? Earth Life.

[4] Morelle, Rebecca. 30,000-year-old giant virus ‘comes back to life’. BBC News (2014).

[5] Pivarski, Jim. Viruses have no color. Coffeeshop Physics.

[6] Campillo-Balderas, José A., Antonio Lazcano, and Arturo Becerra. “Viral genome size distribution does not correlate with the antiquity of the host lineages.” Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 3 (2015): 143.

[7] Philippe, Nadège, Matthieu Legendre, Gabriel Doutre, Yohann Couté, Olivier Poirot, Magali Lescot, Defne Arslan et al. “Pandoraviruses: amoeba viruses with genomes up to 2.5 Mb reaching that of parasitic eukaryotes.” Science 341, no. 6143 (2013): 281-286.

[8] Corradi, Nicolas, Jean-François Pombert, Laurent Farinelli, Elizabeth S. Didier, and Patrick J. Keeling. “The complete sequence of the smallest known nuclear genome from the microsporidian Encephalitozoon intestinalis.” Nature Communications 1, no. 1 (2010): 1-7.

[9] Schulz, Frederik, Lauren Alteio, Danielle Goudeau, Elizabeth M. Ryan, B. Yu Feiqiao, Rex R. Malmstrom, Jeffrey Blanchard, and Tanja Woyke. “Hidden diversity of soil giant viruses.” Nature Communications 9, no. 1 (2018): 1-9.

[10] Abergel, Chantal, Matthieu Legendre, and Jean-Michel Claverie. “The rapidly expanding universe of giant viruses: Mimivirus, Pandoravirus, Pithovirus and Mollivirus.” FEMS Microbiology Reviews 39, no. 6 (2015): 779-796.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- Freshwater Mussels are Declining: Why Should You Care, and What Can You Do?

- The Story of Chestnuts in North America: How a Forest Giant Disappeared from American Forests and Culture

- Friendships, Betrayals, and Reputations in the Animal Kingdom

- Why Don't Apes Have Tails?

- Giant Bacteria, Giant Genomes

- More ›