GRAD SCHOOL DIARIES

human dimensions ethics science and society sexism

When does order matter when listing the sexes? Always

Post by kzarrellasmith

I am a PhD student studying the movements of marine organisms. Recently, I was preparing my first first-author publication when I stumbled upon a dilemma: do I list female crabs or male crabs first in a study comparing the two? Foundational works examining green crab behavior exclusively followed males [1] so it was important to recognize biological sex as a variable in our studies. The R coding program I was using lists variables in alphabetical order, so in this case, females appear before males. How was it though, that after decades of struggling against sexism and suffering its severe consequences, seeing “females and males” felt so unnatural compared to “males and females”? I thought to myself, “I will just change the ordering in my paper to match the R outputs. That would give me parallel structure in the presentation and discussion of the data. Alternatively, why would I specifically add code to establish males before females when we are most interested in what the females are doing?”

But shortly thereafter, doubt and fear crept in. I am an early-career cis woman (female) on the verge of submitting a manuscript with two other females on the author line, and none of us have PhDs. Reviewer comments from the papers that my peers have submitted whittled away at my resolve to list females first: “It would probably…be beneficial to find one or two male biologists to work with (or at least obtain internal peer review from, but better yet as active co-authors)” and “Perhaps it is not so surprising that on average male doctoral students co-author one more paper than female doctoral students, just as, on average, male doctoral students can probably run a mile a bit faster than female doctoral students,” says a PLOS ONE reviewer to two female evolutionary biologists in the singular review that accompanied their manuscript rejection [2].

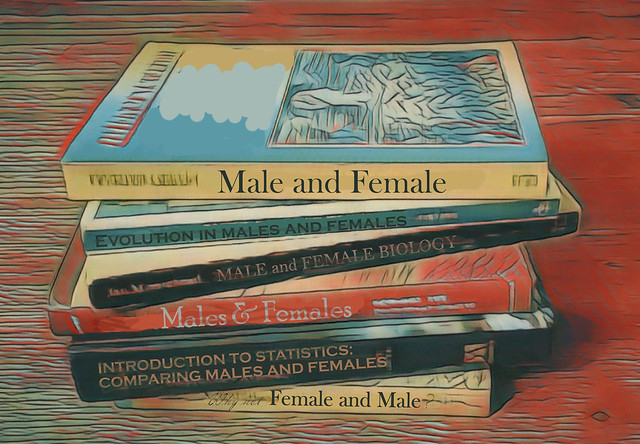

Unfortunately, there is further evidence that requires me to proceed with caution. Though biological sex is not binary in humans and is often confused with gender, analyses of female and male publication rates based on inferences from author names are most readily available. Manuscripts of first-author females and males are submitted for review at equal rates, yet females receive lower peer review scores and are more likely to be rejected after peer review [3]. Females are also published at lower rates in prestigious journals [4]. Out of 20 randomly chosen Ecology, Evolution, and Statistics textbooks and popular science books on my shelf (by authors such as Darwin, Dawkins, Gould, and Zar), all authors present the concept of “males and females” as if some natural ordering exists for these terms. By breaking this tradition, would I be tempting reviewers to reject our work?

Ordering by importance is a common writing tool in which the writer organizes words according to a hierarchy of value. When teaching English to new speakers, it is stated, “The sequence of words is critical when communicating in English because it can impact the meaning of what you’re trying to say” [5]. Had there been no intention to establish a hierarchy when listing two sexes and the choice is then by default random, the laws of probability would dictate that the terms are equally exchanged in the list. However, this is not the case in the vast majority of publications or common English language, which is not a grammatically gendered language in which most nouns are assigned a gender unrelated to their definition. Should you seek independent evidence of this ordering, try perusing your own bookshelf.

Figure 1. Checking the science books on my shelf, I found males listed before females in every case, including the textbook, “Male, Female. The Evolution of Human Sex Differences” [6]. Image credit: Katrina Zarrella Smith.

Where listing males first came from is unknown, but it extends at least as far back as multiple millennia [7]. When I searched the terms “hierarchical male and female description” in Google, a flood of literature reinforcing a hierarchy of males over females came to light. For example, a professor of Evolutionary Biology states in his textbook, “Since males, in general, have been more dominant than females, they possess more political power. Most high-status positions are held by males” [8]. He further extends this narrative to all vertebrates, “In most cases within vertebrates, males dominate females.” Such a line of reasoning places high value on the roles of males compared to females. Yet, remarkably this same evolutionary biologist might understand that reproduction is a widely accepted major process in evolution, and furthermore that females ultimately shape and give birth to the next generation, playing a pivotal role in bringing about life [9]. Yet interestingly, power is viewed and valued through the lens of the traditional roles that males have historically played.

Scientists are a product of their culture, which influences their values, goals, and thought processes. This professor’s straightforward statements are symptomatic of a hierarchical and misogynistic culture. It is unlikely that he was naïve to the implications of his work, but it is also likely that he felt validated for expounding an overarching theory of the sexes as evidenced by his consistent employment at a university where he was responsible for shaping the minds of scientists for over five decades. Though some scientists work to actively avoid lines of research with cultural and ethical implications, others seek it out and acknowledge their implications for society, even going so far as to advocate for positive societal outcomes [10, 11]. Many scientists do neither, leaving the ramifications of their work with either intended or unintended harmful consequences.

The extent to which misogyny has impacted individual well-being and scientific thought is emerging [12, 13]. We can no longer avoid systemic issues and are called herein to examine every level of our own scientific work, including how we list our data or form our book titles. It is not surprising that something as small as the listing of sexes, whether in science or any other venue, has contributed to harming females because it is a tool that reinforces a male hierarchy. Moreover, a perpetual incomplete listing of the biological sexes that disregards intersex in human systems, among others, contributes to the false dichotomy of the sexes and further harm to many individuals [14]. Researchers should feel emboldened to break with tradition and embrace thoughtful consideration of how three seemingly simple words in a crab biology paper, “females and males” [15] could help to revolutionize how an entire class of people is viewed.

REFERENCES

[1] Atkinson RJA, Parsons AJ. 1973. Seasonal patterns of migration and locomotor rhythmicity in populations of Carcinus. Netherlands Journal of Sea Research 7:81–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/0077-7579(73)90034-3

[2] Bernstein R. 2015. PLOS ONE ousts reviewer, editor after sexist peer-review storm. Science Insider. https://doi:10.1126/science.aab2568

[3] Fox CW, Paine CET. 2019. Gender differences in peer review outcomes and manuscript impact at six journals of ecology and evolution. Ecology and Evolution, 9:3599–619. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.4993

[4] Holman L, Stuart-Fox D, Hauser CE. 2018. The gender gap in science: How long until women are equally represented? PLOS Biology, 16:e2004956. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2004956

[5] ETS. 2015. The importance of word order in English. www.toeflgoanywhere.org/importance-word-order-english

[6] Geary D. 2020. Male, female. The evolution of human sex differences. Third edition, American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C.

[7] Klatch RE. 2001. Right-wing movements in the United States: Women and gender. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, NJ Smelser and PB Baltes (eds), Elsevier Ltd., Amsterdam.

[8] Hermann H. 2017. Dominance and aggression in humans and other animals. The great game of life. Academic Press, Cambridge, MA.

[9] Andersson M. 1994. Sexual selection. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

[10] Levins R, Lewontin R. 1985. The dialectical biologist. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

[11] Ripple WJ, Wolf C, Newsome TM, Barnard P, Moomaw WR. 2020. World scientists’ warning of a climate emergency. BioScience 70: 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biz088

[12] Davies SW, et al. 2021. Promoting inclusive metrics of success and impact to dismantle a discriminatory reward system in science. PLOS Biology, 19(6): e3001282. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001282

[13] Oreskes N. 2020. Racism and sexism in science haven’t disappeared. Scientific American. www.scientificamerican.com/article/racism-and-sexism-in-science-havent-disappeared/

[14] ISNA. 2021. Intersex Society of North America. https://isna.org/faq/what_is_intersex/

[15] Zarrella-Smith KA, Woodall JN, Ryan A, Fury NB, Goldstein JS. 2022. Seasonal estuarine movements of green crabs revealed by acoustic telemetry. Marine Ecology Progress Series 681: 129–143. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13927

## More From Thats Life [Science]