Emily Melzer EARTH'S ORGANISMS

bacteria physics cytoplasm cell biology glass biophysics

Life, the universe, and everything: Dreams of being a biophysicist

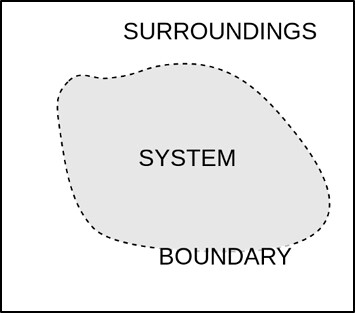

My short visit to the physics department was fabulous. Mostly I had no idea what the speaker was talking about, and I definitely didn’t understand 90% of the questions and formulas brought up by audience members. But honestly, it was awesome. Yes, I know – I write for a life science blog and I spend most of my time thinking about cells, DNA, and proteins. But is a cell really much different from a thermodynamic system where a physicist looks at matter and energy or an electromagnetic field with currents and electromotive force? Not really. To a physicist, a cell is just another physical system. And as a microbiologist sitting in a room full of physicists, I was fascinated by this point of view. I wrote down over ten terms and laws that I later had to google, and looked up a couple of papers that had come out of the speaker’s lab to try and wrap my head around what he was saying. This post is my attempt to discuss the magic that is biophysics, and to the actual physicists reading this: go easy on me.

Fig. 1: To a physicist, a cell is just another physical system. Source: Krauss via Wikipedia

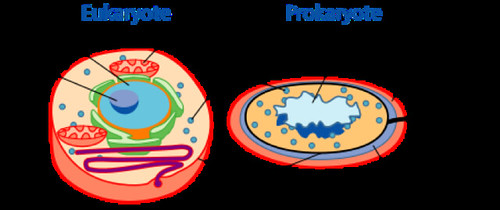

What did I learn at this talk? The first thing I learned was that bacterial cells are much more crowded than eukaryotic cells (such as human cells or plant cells). In fact, they are so crowded that if you pop them open, they are 3 times more viscous than their eukaryotic counterparts! Just how viscous are they? Biologists like to think about the inside of a cell (the cytoplasm) as a liquid environment. This is important because there are a lot of moving parts in the cell. In bacteria especially, diffusion is the principal way for proteins and other cellular elements to get where they need to go, and diffusion only works in liquids. But this physicist is standing in front of a room full of other physicists (and me) and telling us that the inside of a cell isn’t exactly liquid. It’s more like glass. Apparently, glass does this cool thing where it is technically characterized as a solid after being heated, even though it flows like a liquid. And it turns out that the cytoplasm is so jam-packed with stuff that it actually behaves the same as this heated glass. i.e., it flows like liquid, but is characterized as solid [1].

Fig. 2: Diagrams of the cytoplasm can be misleading – doesn’t it seem like it’s so spacious? In reality, those cells are jam-packed with stuff! Source: National Center for Biotechnology Information via Wikipedia

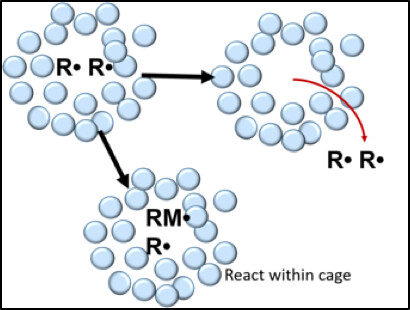

Why is all of this important to a microbiologist studying cellular biology? Thinking about everything that needs to happen in the cell for proper function and propagation is mind boggling as it is: Countless genes need to be transcribed and translated into proteins, that need to get to a particular site where they need to interact with highly specific partners and work on a certain substrate, only under some conditions, but not others – or else it throws the whole system out of whack! Isn’t it impressive that cells actually do what they need to do? Now add to that complicated scenario that the cytoplasm isn’t actually this bag of water where proteins are free to float around until they fulfill their destiny. Not only is this place crowded as hell, but it also isn’t a true liquid environment like we thought. Additionally, if the cytoplasm really is like glass, then not even one molecule can move without everything else around it moving. This means that motion in the cytoplasm isn’t smooth, but made up of “caging” and “steps”: most of the time the molecule is stuck (caged) in one area. Every once in a while, however, the molecule is able to step over to a new area where it will be caged for a while longer until it is able to step over again. This inhibited motion means that it could take a while for a given molecule to get to where it needs to go.

Fig. 3: The cytoplasm is so crowded that molecules are mostly “caged” in a given area, and every so often can “step”/“jump” over to their next cage, and so on until they reach their destination. Source: Sanoica j via Wikipedia

While this may sound like a minor modification to how we see cellular dynamics, this blend of ideas from the physics and biology fields is an excellent example of why interdisciplinary collaborations are so important. It also inspired me to try to branch out of my field – look at things from a different perspective, and maybe take a physics course. Biology is magically complicated, and we need all the help we can get to figure out what is going on. In the meantime, I will continue to play biophysicist and think about the elastic forces that work on my protein of interest.

References

[1] Parry, Bradley R., Ivan V. Surovtsev, Matthew T. Cabeen, Corey S. O’Hern, Eric R. Dufresne, and Christine Jacobs-Wagner. “The bacterial cytoplasm has glass-like properties and is fluidized by metabolic activity.” Cell 156, no. 1 (2014): 183-194.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- Freshwater Mussels are Declining: Why Should You Care, and What Can You Do?

- The Story of Chestnuts in North America: How a Forest Giant Disappeared from American Forests and Culture

- Friendships, Betrayals, and Reputations in the Animal Kingdom

- Why Don't Apes Have Tails?

- Giant Bacteria, Giant Genomes

- More ›