Guest Writer EARTH'S ORGANISMS

microbiology physiology adaptation bacteria

Alien Microbes: How studying hyperthermophiles can help us discover life on other planets

When you think about a microbe, the first thing you picture is probably your run-of-the-mill yeast or the bacteria that lives in your gut. But microbes live in every place on earth, from the pits of volcanoes to the middle of glaciers. Microbes that live in extremely hot temperature environments from 80 - 100°C (176 - 212°F) are called hyperthermophiles, or “super heat loving” organisms. These type of organisms, mainly archaea and bacteria, were some of the first living things on earth 3.9 billion years ago [1]. We might even find a hyperthermophile-like organism on another planet where only the toughest of life can survive.

Every living thing that we know of needs water to survive, so wherever in the world hyperthermophiles dwell, liquid is a must. However, because of low solubility of oxygen at high temperatures, the vast majority of habitats for the microbes are anaerobic, meaning without oxygen [2]. These are the main features that connect hyperthermophiles together and they have been found in environments all over the world. As long as there’s super hot water you could find a hyperthermophile!

Figure 1 Solfartic fields near the volcanic crater area Solfatara in Italy– terrestrial hyperthermophiles inhabit fields like these heated by volcanic gases. Source: Aph at German Wikipedia, License CC-BY-SA 3.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Solfatara_2.jpg

On land, high temperature sulfur fields (Solfartic fields) are made of mud and soil where magma chambers a couple kilometers below the earth spew out volcanic hot gas [2]. These boiling mud fields are usually close to volcanoes and the surrounding waters are around 100°C (212°F). Hyperthermophiles have been found in a many different hot springs, from the ones found in Yellowstone National Park, to volcanic rift zones in Iceland. They are even present in Japanese *onsens *used for bathing and restoration [1].

Figure 2 A “Black Smoker” hydrothermal vent spewing out sulfide minerals. These are popular aquatic habitats for hyperthermophiles. Source: NOAA, License CC-BY-SA (Via Wikimedia)

Under the sea, these microbes can be found from the caps of the waves to the bottom of the ocean, as long as there is a hydrothermal vent around. In these areas, often near volcanos or tectonic plate lines, hot fluid is released up into the ocean [3]. The most intense vents, called “black smokers”, emit hot gases up to 400°C (752°F) from the sea floor into the freezing ocean; since these streams happen in bursts, and not all the time, hyperthermophiles must be able to survive both the intense heat and the 2.8°C (37°F) water when the vents are not spewing [3]! They must also adapt to the high pressure and lack of oxygen.

But how can any living thing survive in such high temperatures where DNA, RNA, and proteins, all necessary for life, are easily unraveled? The answer is with many different coping mechanisms! In fact, the heat even offers some advantages to the microbes: higher rates of reactions, more membrane fluidity, and better solubility of necessary chemicals [4].

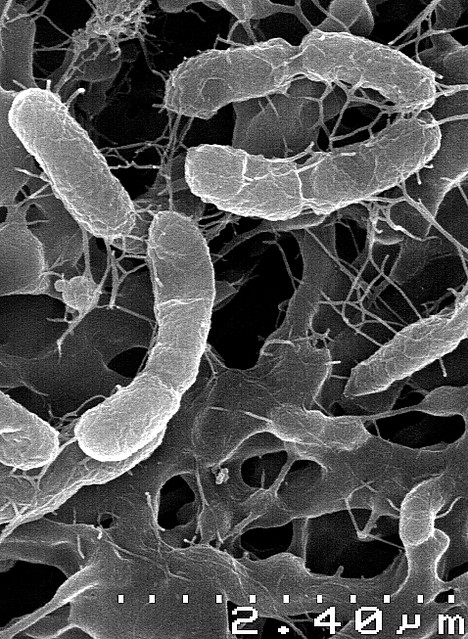

Figure 3 A Scanning Electron Microscopy image of Venenivibrio stagnispumantis, a facultative thermophile that can survive at high and low temperatures. Source: Adrian Hetzer, License CC-BY-SA (Via Wikipedia)

Hyperthermophiles have specialized rigid enzymes that do not unfold in the heat, unlike in most organisms, and actually work best at high temperatures [4]. They also have slightly different cell membranes with some key features that promote stability. Hyperthermophiles generally have longer hydrocarbon chains in their membranes which keep them from becoming fluid and unstable in higher temperatures– a strong membrane is vital to keep the cell alive [5]! Heat Shock proteins, which are actually in all organisms, are particularly important in hyperthermophiles. They refold proteins that were unfolded by the heat and make them function again, sort them into the correct area of the cell, and generally protect cells in high heat. Hyperthermophiles have an abundance of these specifically suited for extreme temperatures [5].

It is amazing that extreme conditions can support life on Earth, and scientists are still researching all the small ways that these organisms protect themselves against their extreme habitats. If we are able to better understand and recreate these survival techniques, maybe we can engineer an organism that can live on other planets, or at least understand how an alien organism can live successfully on their hardly habitable planet! Astrobiologists have hypothesized that planets with water, carbon, and necessary metabolites could host alien life, and have pinpointed several exoplanets out of our solar system where this is possible. With hugely varying pH, temperatures, and pressures, those organisms would look like some of the extremophiles here on Earth.

Hyperthermophiles’ unique physiology also has potential for use in biotechnology. Archaea that produce ethane have been great candidates for producing biofuel en mass. With their ability to withstand the heat and acidity of biofuel production environments, these microbes could produce ethanol quickly and easily [6]. The seemingly small adaptations of these organisms have so many potential uses from medicine, to fuel, to exploration of alien organisms– hyperthermophiles are indeed the hottest microbe on the market!

References

Stetter KO, Fiala G, Huber G, Huber R, Segerer A. Hyperthermophilic microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;75(2-3):117-124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04089.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04089.x.

Karl O Stetter. Hyperthermophiles in the history of life. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2006;361(1474):1837-1843. http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/361/1474/1837.abstract. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1907.

Prieur D, Erauso G, Jeanthon C. Hyperthermophilic life at deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Planet Space Sci. 1995;43(1-2):115-122.

Claire Vieille, Gregory J. Zeikus. Hyperthermophilic enzymes: Sources, uses, and molecular mechanisms for thermostability. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2001;65(1):1-43. http://mmbr.asm.org/content/65/1/1.abstract. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.1.1-43.2001.

Oger PM, Cario A. Adaptation of the membrane in archaea. Biophysical chemistry. 2013;183:42-56. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23915818. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2013.06.020.

Coker, James A. “Extremophiles and biotechnology: current uses and prospects.” F1000Research5 (March 24, 2016): 396. Accessed March 4, 2018. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7432.1.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- Freshwater Mussels are Declining: Why Should You Care, and What Can You Do?

- The Story of Chestnuts in North America: How a Forest Giant Disappeared from American Forests and Culture

- Friendships, Betrayals, and Reputations in the Animal Kingdom

- Why Don't Apes Have Tails?

- Giant Bacteria, Giant Genomes

- More ›