Jake Barnett GRAD SCHOOL DIARIES

fungi bacteria climate change soil microbiome field work biodiversity

Secrets of the Soil: Searching for Stories from a Warming Climate

The creature was monstrous - from an ant’s perspective, at least. I had been sifting through samples of forest soil all morning, pondering the invisible microbes that might live there, when I was startled by the appearance of a comparatively massive grub. I’m not sure of the species, but it was likely a larvae that would soon turn into a good-sized beetle.

Figure 1. The beetle grub I found while sifting through forest soil, held in the palm of my gloved hand for size reference. Image credit: Jacob Barnett

While exciting, this insect was just one of a vast multitude of living things in the soil. No one knows exactly how many there are, but scientists have already discovered many thousands of soil-dwelling species [1], representing about 25% of the Earth’s biodiversity [2]. Most of these organisms are microscopic bacteria and fungi that are invisible to our eyes. With the right tools, however, the “secret” soil creatures can be revealed and studied. I had gone out into the field to collect these microbes, and bring them back to the lab where I could help reveal their stories.

You may be wondering, why should I care what these invisible soil creatures are doing anyway? First of all, you can thank them for the fact that we are not buried in dead leaves and animal carcasses right now. Soil microbes are decomposers [3, 4]: living things that break down dead materials and return them to the ground, where they can be recycled as plants grow.

What you may not realize is that greenhouse gases (such as carbon dioxide and methane) are also produced by this process of decomposition. As soil microbes do their thing, they help control whether greenhouse gases get stored underground or released into the air. If more of the carbon-containing gases end up the atmosphere, this could trap more heat on Earth through the greenhouse effect and thus speed up shifts in the global climate. Since two-thirds or more of global carbon stores on land are kept in soil [5], the microscopic creatures I am after could potentially have a big effect on our planet’s climate.

Our lab is thus very interested in what might happen to forest soils as the climate continues to warm. To shed light on this question, in September 2017 I travelled to the Harvard Forest in Petersham, MA, where a group of forward-thinking scientists have been experimentally warming the soils for the past 26 years. By burying a series of electrical wires 10 centimeters (about 4 inches) below the surface of the soil in certain marked plots, they have raised the temperature of the soil 5 °C (or 9 °F) above the surrounding untouched areas. It was soil from these experimental warming plots that I had been sifting through all morning.

Figure 2. One of the experimental warming plots from which soil was sampled. If you look closely you can see the metal cylinder with a handle, used to collect the “soil core.” The rectangular metal tray in the bottom of the photo was used to carry the soil back to the sieve. Image credit: Jacob Barnett

Capturing soil microbes for further study back in the lab requires a few simple steps in the field. First, a “soil core” is pulled out of the ground using a metal cylinder with a handle. The clump of soil is then taken to a sieve, where the soil is separated from the “non-soil” such as rocks and roots.

Figure 3. The sieve used to separate soil from “non-soil.” Image credit: Jacob Barnett

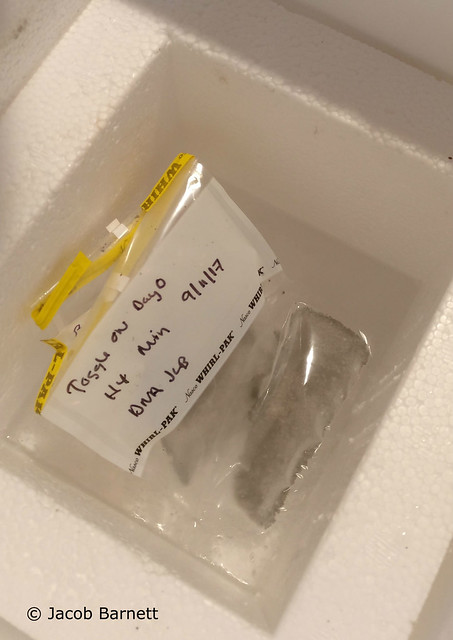

Once the soil has passed through the sieve, we are left with an evenly mixed sample that is then weighed and placed into a plastic bag. Finally, the bagged sample is flash frozen in a bath of dry ice and ethanol - preserving all of the invisible microbes until we can study them further in the lab.

Figure 4. A labeled bag of soil getting flash frozen in a bath of dry ice and ethanol. Image credit: Jacob Barnett

Now that we have the bags of frozen soils back at UMass, the next step will be to extract the DNA of whatever living things were captured in the samples. Since the bacteria and fungi we are interested in are too small to see with the naked eye, we use genetic techniques to study them. Each organism’s unique DNA sequence is like a “barcode” that we can use to identify it. When we pull the DNA out of a soil sample, we grab “barcodes” from nearly all of the organisms that were there at that time, giving us a snapshot of the community at work in the soil.

Our lab is also exploring cutting-edge techniques for finding which microbes are most active in this community and then measuring what they are actually doing. This information could provide insight into how these organisms affect the movement of carbon-containing greenhouse gases in and out of the soil.

What secrets will these invisible creatures hold? Will their story shed light on how forest soils might respond to global warming? Will there be any more surprises like that massive beetle grub? So far the evidence suggests soil warming starts a cycle that releases more and more carbon into the atmosphere [6], but there is still work to be done to figure out how this all happens. These questions will keep me busy in the years ahead as a PhD student. Discovery awaits - but first I have a lot of lab work to do!

References:

[1] Brussaard, Lijbert. “Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning in Soil.” Ambio 26.8 (1997): 563-570

[2] “Soils Host a Quarter of our Planet’s Biodiversity. International Year of Soils 2015.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Fact Sheet (2015)

[3] Pold, Grace. “Death Stinks - Literally.” That’s Life [Science], August 2, 2017. http://thatslifesci.com.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com/2017-08-02-Death-Stinks-GPold/

[4] Kowalski, Kathiann. “Recycling the Dead.” Science News for Students. September 27, 2014. https://www.sciencenewsforstudents.org/article/recycling-dead

[5] Heinemeyer, A., et al. “Exploring the “overflow tap” theory: linking forest soil CO2 fluxes and individual mycorrhizosphere components to photosynthesis.” Biogeosciences 9.1 (2012): 79-95.

[6] Melillo, J., et al. “Long-term pattern and magnitude of soil carbon feedback to the climate system in a warming world.” Science 358 (2017): 101-105.

Additional Links

Blanchard Lab at UMass: https://www.bio.umass.edu/micro/blanchard/

Harvard Forest: http://harvardforest.fas.harvard.edu/

Broadley, Hannah. “Cryptic Species Hide in Plain Sight.” That’s Life [Science], June 6, 2016.

Falconi, Nereyda. “Ask your Food for its DNA ID.” That’s Life [Science], April 23, 2017.