Kadambari Devarajan EARTH'S ORGANISMS

ecology species biodiversity adaptation interactions

You Scratch My Back and I’ll Scratch Yours

It’s not all blood and gore, or predation and cut-throat competition in the natural world. Species interact in many different ways, resulting in fascinating and unusual relationships between different organisms. These interactions involve a degree of cooperation, where a pair of species (sometimes more) ‘help’ each other out. Such mutually beneficial interactions, where the interacting species benefit in some way from the relationship, in an unusual instance of ‘you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours’, is called a mutualism. Such mutualisms can be from species that are very different, like those between ants and plants, or fairly similar, as found with some species of birds.

However, not all parties involved may gain a direct benefit. If in a pair of species, one gets a benefit while the other doesn’t, but is not harmed either, such an association is called commensalism. On the other hand, if one derives a benefit while the other organism is negatively affected, the relation is classified as parasitism. Here, we will look at some examples of mutualism and commensalism, focusing on cooperation and coexistence between species in different systems.

Ants and Acacia

Figure 1. Whistling thorn acacia (Acacia drepanolobium) and several arboreal ant species (including Crematogaster nigriceps). (Source: Wikipedia Commons)

Ant-plant mutualisms have been widely studied in several parts of the world. The whistling thorn acacia (Acacia drepanolobium) is a commonly occurring tree that is native to East Africa. They offer rewards such as shelter in the form of bulbous, thorny structures called domatia and secretions such as nectar to different species of ants. In return for the food and shelter provided by the acacia, the ants offer another line of defense from mega-herbivores such as elephants and giraffes, as well herbivorous invertebrates [1].

In some parts of Africa, there can be even four species of ants (Tetraponera penzigi, Crematogaster nigriceps, Crematogaster mimosae, and Crematogaster sjostedti) forming mutualistic complexes with the tree species [1]. The strength and degree of the mutualism between each ant species and the acacia can vary. The competition between the ant species for exclusive rights on an individual tree results in strategies to minimize occurrence of the other species – such as sneakily ‘trimming’ the tree so that contact between neighboring trees is low and thereby decreasing movement by ants between trees. They even have unique adaptations that give one species a competitive advantage that they can then use to sabotage any invasion by another species, such as ants that utilize the domatia but not the nectar. These ants destroy the nectar glands in the tree in order to make it less appealing to the competing species with a fondness for nectar [2].

The story gets curiouser and curiouser. ‘Rewards’ like domatia and nectar are expensive for the acacia, so in times or areas in which there are few large herbivores that feed on them, the acacia actually ‘withdraw’ these rewards, resulting in a breakdown of the mutualism [3].

Birds and Badgers

Figure 2. The honey badger (Mellivora capensis) and pale chanting goshawk (Melierax canorus). (Source: Wikipedia Commons)

The honey badger (Mellivora capensis) is a mammal that is related to weasels, martens, and otters, and is found in parts of Africa and Asia. While they are omnivorous, feeding on insects, birds, eggs, small mammals and reptiles, and even berries and roots, they have a soft spot for bee honey. A number of birds and mammals are known to form associations with the honey badger, following it around in the hope of feeding on the prey that escape the honey badger while it digs and forages for food. These ‘followers’ include birds such as pale chanting goshawk (Melierax canorus), greater honeyguide (Indicator indicator), and spotted eagle-owl (Bubo africanus), as well as mammals like black-backed jackal (Canis mesomelas) and African wildcat (Felis lybica).

In this case, the associated species all derive some benefits while the honey badger does not get any. However, the association is not really detrimental to the honey badger, resulting in commensalism - ‘You can watch as long as you don’t disturb me!’

Cleaners in Coral Reefs

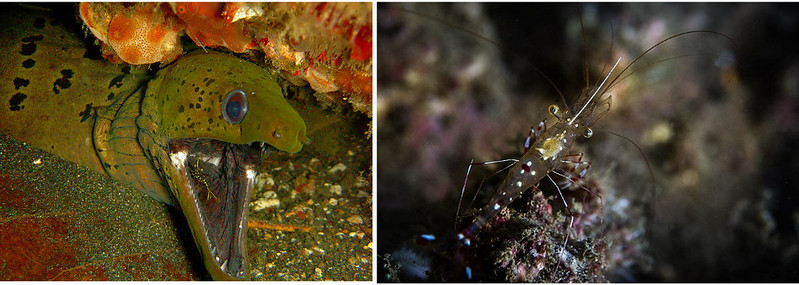

Figure 3 Moray eel and cleaner shrimp. (Source: Wikipedia Commons)

Coral reefs are complex and fragile ecosystems, beautiful, spectacularly colorful, and with a host of delightful and fascinating organisms and interactions. Remember Jacques from Finding Nemo? He was a cleaner shrimp similar to the one in the image helping keep a moray eel clean. Cleaner fish such as wrasse, pipefish, and gobies as well as cleaner shrimp form symbiotic associations with ‘client’ fish that are usually much larger. The hosts ‘clean’ the clients, at times even maintaining a ‘cleaning station’. They remove parasites and dead skin – a win-win for both sides since this interaction results in better health for the clients while providing the ‘cleaners’ with food in the form of ectoparasites, mucus, and tissue from the client fish.

These are just a few examples of the sheer variety of interactions among organisms. They seem to cover the spectrum from collaborative to competitive, clandestine to cut-throat, sneaky to sanguine. Next time you’re out someplace, diving in coral reefs or watching birds in the garden, will you be able to label the interactions between different species?

Further Reading:

Finding the perfect partner by Luis Aguirre

Pollination 101 by Luis Aguirre

Charity cases in nature - when are animals more likely to be altruistic? By Lian Guo

References:

[1] Goheen J.R., and Palmer T.M. (2010) “Defensive plant-ants stabilize megaherbivore-driven landscape change in an African savannah.” Current Biology 20, 1–5.

[2] Palmer T.M., and Brody A.K. (2007) “Mutualism as reciprocal exploitation: African plant-ants defend foliar but not reproductive structures.” Ecology 88:3004–3011.

[3] Palmer T.M., Stanton M.L., Young T.P., Goheen J.R., Pringle R.M., and Karban R. (2008) “Breakdown of an ant-plant mutualism follows the loss of large herbivores from an African savannah.” Science 319(5860) 192-195.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- Freshwater Mussels are Declining: Why Should You Care, and What Can You Do?

- The Story of Chestnuts in North America: How a Forest Giant Disappeared from American Forests and Culture

- Friendships, Betrayals, and Reputations in the Animal Kingdom

- Why Don't Apes Have Tails?

- Giant Bacteria, Giant Genomes

- More ›