Lian Guo OUR ECOSYSTEMS

seafood human health fish consumption advisories

Do we have all the data needed to make safe choices about seafood?

When choosing seafood in the grocery store, restaurant, or fish market, there’s lots of advice out there in the world:

“Buy fresh fish.” “Buy local fish.”

“Only buy farmed fish.” “Only buy wild-caught fish.”

“Don’t eat raw fish unless it’s been frozen.” “Don’t eat raw fish when pregnant.”

These are commonly shared pieces of advice between friends and family to help us avoid food poisoning or make more sustainable food choices. Most people don’t realize that there is another set of advice published by federal and local governments that aims to help seafood consumers minimize their intake of contaminated fish. While food poisoning has an immediate, visible effect on our health, the effect of contaminants often operates on longer time-scales and manifests in pernicious health problems, including immune disorders, neurological diseases, and even cancer [1, 2, 3]. As a result, using fish consumption advisories is extremely important for those who regularly eat seafood.

Figure 1. No matter how delicious this fish looks, you should be aware of how it may impact your long-term health. (Photo by Maxim Krayushkin)

For more information on fish consumption advisories and how to find advice about the fish you eat, check out my first post, “Is it possible to eat too much fish?”. Now that you know how to find fish consumption advisories, we are going to explore what current state-specific advisories are missing and how they could be improved to help seafood consumers make healthier seafood choices.

[Note: this post includes unpublished personal observations from an ongoing research project I am involved with, and are meant to indicate knowledge gaps.]

Toxicological sampling practices do not always consider fish ecology

Surprisingly, fish used for the toxicological testing that determines advisories are collected from few locations, relatively infrequently, and include a limited number of species. For states with coastlines, fish consumption advisories are often based on aggregated results from the entire coast, meaning that fish caught hundreds of miles away from one another are used to calculate a coast-wide advisory. Another interesting trend is that fish from freshwater systems tend to be tested on an annual basis, while marine fish are tested sometimes as little as once a decade. However, people are consuming fish from both of these ecosystems. Depending on the state, testing focuses on a few “indicator species,” which are expected to reflect levels of contaminants of other fish living in the same system. Since we know that fish found higher on the food chain or are longer-lived tend to accumulate more contaminants, we should also be taking a species’ ecology into account when choosing which species to sample and how often to sample them.

While some data is certainly better than none at all, how robust is the data that is used to make fish consumption advisories? Are we missing potential human health risks through inconsistencies in sampling practices?

Figure 2. Fishermen wait patiently to catch fish to take home. (Photo by Ynote)

Fish consumption advisories are almost exclusively for mercury-contaminated fish

Compared to other contaminants, accumulation of mercury in fishes and humans via fish-consumption is well-studied, especially regarding mercury’s negative effects on human neurodevelopment. Mercury also cannot be removed from fish tissue by cooking, meaning there are not alternative ways to prepare fish to reduce mercury contamination. These are possible reasons why advisories are almost all based on mercury levels in fish tissue, and ignore other contaminants that also enter humans through fish consumption.

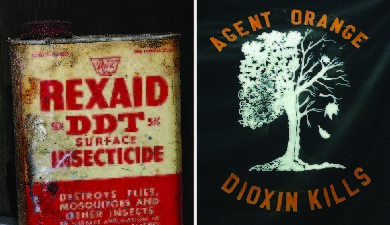

While mercury is the poster child of concern, there are numerous other contaminants that have negative health impacts on humans, including a number of persistent organic pollutants (e.g. DDT, dioxins, PCBs) which once absorbed, are stored in the fatty tissues of animals. This narrow focus on mercury ignores that there are diverse cultural practices surrounding fish preparation and cooking, wherein contaminant-laden skin, fat, intestines, or liver may be consumed on a regular basis. As a result, current fish toxicology testing practices are likely underestimating the potential health hazard of frequent fish consumption, particularly for cultural minorities in the United States.

The danger of these contaminants is that their molecular structure resembles that of our natural hormones, and therefore they can interact with and often disrupt our normal biological processes [4]. However, testing for these contaminants seems to only occur when the general public files complaints or concerns about fish contamination. Beyond the chemicals we already know are bad for us, ~2,000 new synthetic chemicals are introduced to our households and environment every year. Even scarier, we have no idea how eating combinations of these various contaminants affects our health.

Figure 3. Left: An old can of DDT, an insecticide that famously led to severe declines in bird populations and still pollutes our waterways. (Photo by Brad Smith) Right: Dioxins became famous as the chemical compounds in the herbicide Agent Orange that caused severe health problems in those exposed to it during the Vietnam War. (Photo by jectre)

It would be in the best interests of public health to expand toxicological testing to improve coverage of when, where, and what fish are tested. As far as contaminants of interest, we should be testing fish for more contaminants with known negative human health impacts. As it stands, federal and state governments have very limited funding for toxicological testing, which is likely why they prioritize mercury testing and have inconsistent, sparse testing practices. Even so, given the importance of seafood to human diets and the potential for negative health impacts, this funding should be expanded to improve the scope of testing and provide consumers with the best possible recommendations for safe seafood consumption.

If you want to learn more about how advisories are calculated in your state, call or email your state’s equivalent for Department of Health or Fish & Wildlife agencies. You can call or write to your state legislators and ask them to ensure sufficient funding is directed toward testing of contaminants in fish tissue to establish annual testing practices for more contaminants in more locations, on popularly targeted fish species. Be conscious that until we have better information about contaminant levels in fish, eating fish in moderation (< 2x per week, depending on the species) will allow more time for contaminants to cycle out of your body!

References:

[1] Carpenter, David O. “Exposure to and health effects of volatile PCBs.” Reviews on environmental health 30, no. 2 (2015): 81-92.

[2] Jones, Kevin C., and P. De Voogt. “Persistent organic pollutants (POPs): state of the science.” Environmental pollution 100, no. 1-3 (1999): 209-221.

[3] Lei, Meng, Lun Zhang, Jianjun Lei, Liang Zong, Jiahui Li, Zheng Wu, and Zheng Wang. “Overview of emerging contaminants and associated human health effects.” BioMed research international 2015 (2015).

[4] Reaves, Denise K., Erika Ginsburg, John J. Bang, and Jodie M. Fleming. “Persistent organic pollutants and obesity: are they potential mechanisms for breast cancer promotion?.” Endocrine-related cancer 22, no. 2 (2015): R69-R86.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- La Belle et La Boeuf (NOT!) How do human meat preferences impact climate change?

- Artificial Selection: From Tiny Fish to Empty Dish

- A breath of fresh air: How the great oxygenation event changed life on Earth forever

- The Women Behind the Gun vs. The Women Behind the Bird

- How Community-based Conservation Helps Lemurs

- More ›