GRAD SCHOOL DIARIES

communication human research

From Bill Nye to the ‘Average Joe’: The changing face of science communication

Note: This post is co-authored by TLS contributors Laura Hancock and Evan Kuras.

Science and science communication (also known as “SciComm”) is an integral part of most graduate student scientist’s lives. For me (Laura), (good) science communicators and engaging scientific resources changed the course of my education, career, and life. I can specifically pinpoint two events in my life that formulated my future career and academic passions. And both of them had to do with well communicated science.

When I was ten years old, I participated in an interactive workshop given by Nobel Prize winner William (Bill) Phillips. Even though I can’t remember every bit of information he shared about laser cooling (his research area), I can still picture the entire scene like it was yesterday: I was sitting in the front row of a 200-seat, darkened auditorium next to my older sister. Dr. Phillips was on stage about 12 feet in front of me playing with liquid nitrogen and balloons. He showed us how temperature affects atoms and molecules by freezing inflated balloons in a tall, shiny canister of liquid nitrogen. My main take-away from that night (besides how cold my feet were from the escaping liquid nitrogen) was that he got to play with balloons, so physics couldn’t be all that boring, right? Dare I say, it could even be - gasp - fun.

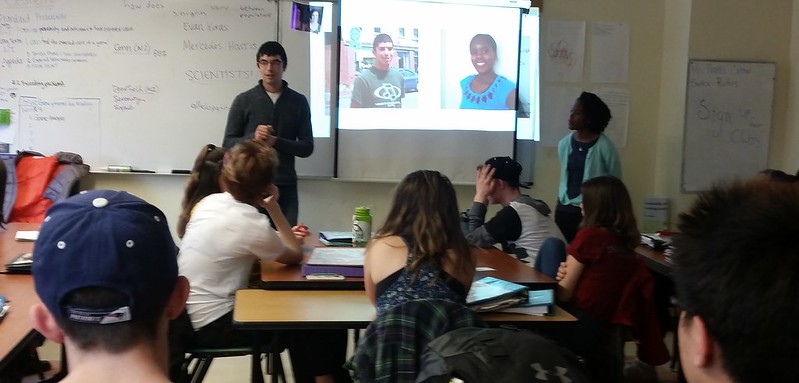

Figure 1. Evan Kuras (the other author of this post) and Mercedes Harris talking about being scientists to a high school class.

Fast forward about 5 years, I’m now an awkward teenager whose main focus in life is to finally convince my mom that I needed a pink razr cell phone (see figure 2!). I had to start reading “Biology: The Dynamics of Life” for biology class. While I had always been fairly interested in animals and the environment, I had never given the science behind these topics much thought. As soon as I started reading the first pages of “Biology” I was in love… with science! All because of the eloquent and creative way that this book described science that I hadn’t even realized was science. The book made it all click for me; being outside wasn’t just a pain because of the sun, dirt, and cold (see my previous post here), being outside meant I was a part of all the cool processes and interactions that had always been happening right in front of my eyes, but that I had been unaware of before. And these interactions were happening not only between what I could see (e.g. plants and animals), but between the nonliving and living parts (microscopic organisms included) of the environment that I couldn’t. Suddenly I saw the world in a whole new way!

Figure 2. Which phone is the best? (Photo credit: Maitri via Flickr)

If you’re reading this post, you likely have some interest in science (or you know the authors). Our question to you is, how did you become interested in science? Was it because of a great science communicator that you enjoyed watching and learning from as a kid or that you appreciate today? Maybe it is Bill Nye, Neil DeGrasse Tyson, or Physics Girl?

Figure 3. Is this not the best theme song?

Or maybe it is the Magic School Bus or Planet Earth that got you hooked. What is it about these people or shows that make them so effective? Good SciComm has a few important elements in common. First, good SciComm knows its audience and adjusts accordingly, like using liquid nitrogen for a fun interactive workshop or referencing a popular movie like Fight Club to explain lobster territorial defense. Second, good SciComm has a goal, whether it is inspiring wonder about atoms or explaining what we know about sexual cannibalism. Third, good SciComm has accurate content from trusted sources, such as a Nobel Prize winner or two scientists doing research about how Pokemon Go relates to people’s experiences with nature. And fourth, good SciComm uses appropriate mediums to reach the right audience in the right way at the right time. These can range from blog posts, to public lectures, to TV shows, to op-eds in the local paper. There are many more elements of good SciComm that you can read about from the Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) or SciComm@Cornell.

The ways in which SciComm is practiced and disseminated have recently been changing quite a bit. Most importantly, science and SciComm are increasingly becoming decentralized. Thanks to social media, technological advances, and interactive citizen science programs such as the Christmas Bird Count, almost anyone, regardless of educational background, can take part in producing scientific knowledge or communicating science to wider audiences. Decentralization allows science to become more available, more accessible, and more affordable, which leads to better understanding of and connection to science by more diverse audiences. But, more widespread and decentralized SciComm can also lead to problems, especially in relation to controversial scientific topics. With so much information available, it can become harder to weed out the accurate information from what is written by people who aren’t as informed about a topic, or even maliciously spreading misinformation. In general, about 70% of Americans believe that science and research are positive for society. However, some topics like vaccine safety or GMOs are more controversial with less consensus between scientists and non-scientists, even though there is general consensus among the scientists who study the topics. For example, 88% of scientists believe that GMOs are safe to consume, but only 37% of U.S. adults believe that.

Here at TLS, we are part of the decentralization of SciComm, which allows us to more efficiently and frequently bring science to you, the reader. But it’s not just us. Graduate students,scientists, and “Average Joe’s” throughout the world are finding their own ways to communicate science. At UMass, some examples include radio shows (like Lab Talk with Laura), blogs (like Time Scavengers), videos (like Nigel Golden’s science-telling about Ground Squirrels and Alaska), and public events (like the TLS Animal Habitats Badge event).

I'm sharing a short vid on a component of my research! Please feel free to comment and share. It'll help for the second iteration of the video! #alaska #wilderness #wildlife #Denali #climatechange #nativeland #ecosystem #Conservation #warming #environment pic.twitter.com/WdVOdM0fl9— Nigel Golden (@scienceizgolden) March 25, 2018

Figure 5. A video made by UMass graduate student scientist Nigel Golden @scienceizgolden, communicating his science about arctic ground squirrels

In April 2018, UMass graduate students came together for an Outreach and Public Engagement Summit where we all shared experiences, resources, and best practices around engaging wider audiences in our work and in so doing helped contribute to the ever expanding field of SciComm. Who knows: maybe a TLS blog post or Nigel’s next video will make that essential difference in teaching something important or inspiring an interest in science. Or maybe you, our reader, will share your interest in science with your friend or cousin in a way they will someday reference as a life changing event!

Figure 6. The Outreach and Public Engagement Summit for UMass graduate students in April 2018 (Photo credit: Elena Sesma).

More From Thats Life [Science]

- CRISPR technology may be a promising tool to combat multidrug resistant fungus C. auris

- How the search for a universal gene forever changed biology: the story of Carl Woese and 16S sequencing

- Quarantine Blues? The Effects of Social Isolation in the Brain

- The Lovebug Effect

- CRISPR: Careful When Running with Genetic Scissors

- More ›