HOW IT WORKS

stress glia social behavior neurogenesis social isolation

Quarantine Blues? The Effects of Social Isolation in the Brain

What happens to your brain during quarantine? What are the damaging effects of chronic social isolation stress and what can you do to reduce these effects? As social distancing measures extensively impact our lives, neuroscientists are striving to understand the effects of social isolation on the brain and its mental health consequences (Fig.1).

Figure 1. Increased number of peer-reviewed publications in the topic of social isolation. Number of publications related to social isolation peaked in 2020. Source: Annabelle Flores-Bonilla, [1]

It Can Happen to Anyone

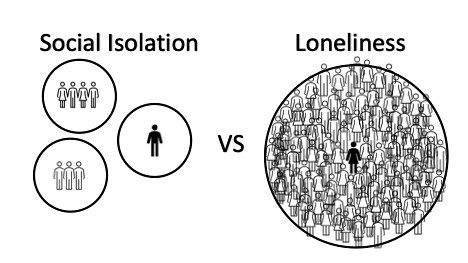

Humans are social by nature and social isolation can have severe consequences on our physical and mental health. Humans can experience social isolation in two different ways: completely cutting off interactions with other humans (Actual Social Isolation) or feeling disconnected from humans around us (Perceived Social Isolation); (Fig. 2) [2]. Risk factors for Actual Social Isolation include living alone, the loss of family or friends, chronic illness, and sensory impairments, which have a higher prevalence for people over the age of 65 [3]. However, young adults in the United States are most at risk for the negative mental health effects of Actual Social Isolation. Within the 20% of adults that live alone in the United States, the youngest adults (18 to 44 years old) report higher rates of anxiety and depression than the older adults (65 years and older) [4,5]. Perceived Social Isolation (i.e. loneliness) is most commonly reported in young men living in individualistic cultures like the United States [6].

Figure 2. Conceptualization of Actual Social Isolation and Perceived Social Isolation (loneliness). Source: Annabelle Flores-Bonilla

Perception vs Reality

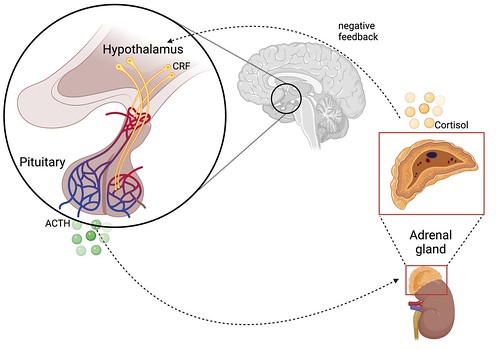

Loneliness can have similar negative effects as Actual Social Isolation because both block the body’s ability to cope with stress in a healthy manner. A healthy response to stress involves communication between the brain and our adrenal glands located on top of the kidneys, which is known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Fig 3). HPA axis fatigue after chronic Social Isolation disrupts the release of cortisol in the adrenal glands, inhibiting negative feedback in the brain [7,8]. Cortisol is the last step in the process that puts the breaks on the stress response. It is involved in a variety of functions, from regulating the immune system to inducing the release of adrenaline for the fight and flight response [9].

Figure 3. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis. Note: ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; CRF, corticotropin-releasing factor. Source: Annabelle Flores-Bonilla via Biorender.com

The Chicken and Egg Enigma

Does Actual Social Isolation cause mental health problems or do mental health problems cause individuals to self-isolate? There is evidence before the pandemic which suggests that both scenarios are possible and that evidence for one does not negate the other. Social withdrawal can be a symptom of many psychiatric disorders, including anxiety, depression, disorders on the autism spectrum, schizophrenia, and personality disorders [10]. However, Primary Social Withdrawal can occur in healthy individuals with no previous mental health illness. In fact, people who experience Primary Social Withdrawal, also known as “hikikomori” (引きこもり, a Japanese word meaning a person or experience of “pulling inward, being confined”), may at first express feelings of content with self-isolation. However, hikikomori are 6.1 times more likely to develop a mood disorder in their lifetime [11,12]. Therefore, regardless of whether self-isolation is voluntary or due to the precautions of the COVID-19 pandemic, chronic social isolation can leave us at a higher risk for experiencing the negative mental health consequences.

Life is Unpredictable

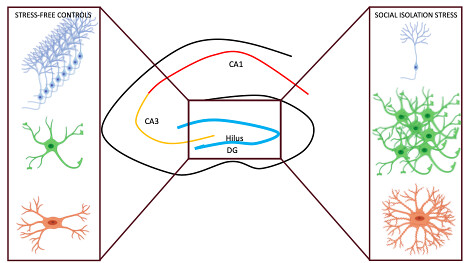

Social isolation does not occur in a vacuum. Stressors in our lives are unpredictable, such as economic loss, dealing with grief, or anxiety about the future; which many of us have felt during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, in a pre-clinical animal research setting, these stressors are limited to the study of Actual Social Isolation (and not loneliness) and to modeling unpredictable chronic stressors such as a scarce, unclean, or disrupted home-cage environment and predator odor cues. Neuroscientists found that male mice that experienced unpredictable chronic stressors plus social isolation showed reduced plasma corticosterone levels (analogous to cortisol) compared to stress-free controls [13]. They also found higher inflammation and a loss of production of new neurons in the hippocampus of socially isolated mice compared to controls, which implies damage and loss of neuronal function in the memory center of the brain (Fig 4) [13]. These results were consistent with accompanying depressive-like behaviors such as the inability to feel pleasure, decreased grooming, and loss of motivation.

Figure 4. Effects of Social Isolation Stress in the Brain. Note: DG, dentate gyrus. Neurons are in blue, astrocytes in green, and microglia in orange. Source: Annabelle Flores-Bonilla via Biorender.com.

An Unexpected Finding

Experiencing social isolation and/or loneliness can take a significant toll on many people’s lives. An upside to isolation caused by the pandemic is a renewed appreciation of social connections and a better understanding of our mental health needs. As COVID-19 restrictions are lifted and people resume in-person interactions, this re-exposure to social life can have a positive impact on our brain as well as our behavior. In fact, and perhaps surprisingly, social isolated mice showed a 46% increase in time spent displaying social behaviors when re-introduced to other mice compared to stress-free control mice [13]. These interactions after experiencing social isolation reduces brain inflammation and improves neuronal growth that leads to better outcomes in mood, specifically decreasing anxiety-like behaviors to stress-free levels [14,15]. As such, when it is safe to do so, if you reconnect with other humans and hug your loved ones a little tighter and a little longer, your brain will be on its way to recovery.

References

[1] National Institutes of Health National Library of Medicine. “Search query: social isolation.” PubMed.gov. Accessed on June 11, 2021.

[2] Holt-Lunstad, Julianne. “Social Isolation and Health” Health Policy Brief (2020): https://doi.org/10.1377/hpb20200622.253235

[3] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. “Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System.” Washington, DC: The National Academies Press (2020): https://doi.org/10.17226/25663.

[4] Schondelmyer, Emily. “Fewer Married Households and More Living Alone.” U.S. Census Bureau (2017): https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2017/08/more-adults-living-without-children.html

[5] File, Thom; and Marlay, Matthew. “Living Alone Has More Impact on Mental Health of Young Adults Than Older Adults.” U.S. Census Bureau (2021): https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/01/young-adults-living-alone-report-anxiety-depression-during-pandemic.html

[6] Barreto, Manuela; Victor, Christina; Hammond, Claudia; Eccles, Alice; Richins, Matt T., and Qualter, Pamela. “Loneliness around the world: Age, gender, and cultural differences in loneliness”. Personality and Individual Differences 169 (2021) 110066; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110066

[7] Mumtaz, Faiza; Imran, Muhammad K., Zubair, Muhammad; and Reza, Ahmad D. “Neurobiology and consequences of social isolation stress in animal model—A comprehensive review.” Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 105 (2018): 1205-1222; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.05.086.

[8] Whitaker, Annie M., and Gilpin, Nicholas W. “Blunted hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal axis response to predator odor predicts high stress reactivity.” Physiology & behavior 147 (2015): 16-22; http://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.03.033

[9] Spencer, Robert L., Deak, Terrence. “A Users Guide to HPA Axis Research.” Physiology & behavior 178 (2017): 43-65; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.11.014

[10] Masi, Gabriele; Berloffa, Stefano; Milone, Annarita; and Brovedani, Paola. “Social withdrawal and gender differences: Clinical phenotypes and biological bases.” Journal of Neuroscience Research 00 (2021); 1–13; https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.24802

[11] Koyama, Asuka; Miyake, Yuko; Kawakami, Norito; Tsuchiya, Masao; Tachimori, Hisateru; and Takeshima, Tadashi. The World Mental Health Japan Survey Group, 2002–2006. “Lifetime prevalence, psychiatric comorbidity and demographic correlates of “hikikomori” in a community population in Japan.” Psychiatry Research 176 (2010): 69–74; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.10.019

[12] Kato, Takahiro A., Kanba, Shigenobu; and Teo, Alan R. “Hikikomori: Multidimensional understanding, assessment and future international perspectives.” Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 73 (2019): 427–440; https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12895

[13] Du Preez, Andrea; Onorato Diletta; Eiben, Inez; Musaelyan, Ksenia; Egeland, Martin; Zunszain, Patricia A., Fernandes, Cathy; Thuret, Sandrine; and Pariante, Carmine M. “Chronic stress followed by social isolation promotes depressive-like behavior, alters microglial and astrocyte biology, and reduces hippocampal neurogenesis in male mice.” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 91 (2021): 24–47; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.015

[14] Biggio, F., Mostallino, M. C., Talanib, G., Loccic, V., Mostallinoa R., Calandra,G., Sanna, E., and Biggio, G. “Social enrichment reverses the isolation-induced deficits of neuronal plasticity in the hippocampus of male rats.” Neuropharmacology 151 (2019) 45–54; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.03.030

[15] Mora-Gallegos, Andrea; and Fornaguera, Jaime. “The effects of environmental enrichment and social isolation and their reversion on anxiety and fear conditioning” Behavioural Processes 158 (2019): 59-69; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2018.10.022.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- CRISPR technology may be a promising tool to combat multidrug resistant fungus C. auris

- How the search for a universal gene forever changed biology: the story of Carl Woese and 16S sequencing

- Quarantine Blues? The Effects of Social Isolation in the Brain

- The Lovebug Effect

- CRISPR: Careful When Running with Genetic Scissors

- More ›