Rachel Bell HOW IT WORKS

sequencing genetics genes microbiology evolution

How the search for a universal gene forever changed biology: the story of Carl Woese and 16S sequencing

In 1977, the field of biology was surprisingly different from today. Scientists divided the tree of life on Earth into two major branches: eukaryotes (complex-celled, frequently multicellular life such as yeast, plants, and animals) and prokaryotes (simple, single-celled life such as E. coli and blue-green algae). Scientists wouldn’t successfully sequence a genome (the entire collection of genes in an organism’s DNA) until 1995 [1], and studying the genetics of microbes was a prohibitively slow, challenging task [2]. Yet, in that same year, Carl Woese and George Fox published findings that would forever change our understanding of the tree of life and launch the field of microbiology into a new era of discovery. But to fully understand the magnitude of their discovery, we must dive deeper into the history of biology.

How biologists classify and organize organisms has changed drastically over the past couple hundred years. Early on, trees of life that described the evolutionary relationships between different species relied on physical characteristics of plants, animals, and fungi—mainly ignoring microbial life [3]. This reliance on physical characteristics and basic functions to define evolutionary relationships made classifying microscopic organisms extremely challenging and inaccurate. Once scientists began looking inside the cells of microbes, they found that some cells were simple while others were more complex. By 1962, they used these cell-level differences to classify organisms into either eukaryotes or prokaryotes [4]. However, this method could not identify the diversity within all the simple-celled organisms grouped into prokaryotes [3]. The true genetic diversity of microbial life remained hidden even up into the 20th century, and the methods that existed to study it left much to be desired.

Figure 1. Ernst Haeckel’s 1866 conception of the tree of life, in which single-celled organisms were all lumped together under one branch and considered a minority within the diversity of life. Image Credit: Ernst Haeckel via Wikimedia Commons.

By the 1960’s, scientists began to understand that genetic similarities could be used to determine the evolutionary relationships of organisms. However, the fact that sequencing the genes (reading the DNA code) of organisms was painstakingly slow and had to be done by hand limited the application of this knowledge to microbes [2]. Creating a tree of life that accurately included microbes seemed an insurmountable task…to almost everyone.

Dr. Carl Woese (1928-2012) was a biophysicist who wanted to create an accurate phylogenetic tree showing the evolutionary relationships of all life on Earth. To do this, he began looking for a single candidate gene that was universally present in all organisms and mutated very slowly over time. The use of such a gene could determine relatedness between species based on sequence similarities and differences, with closely related species having fewer sequence-level differences than distantly related species [5]. He started by looking at genes that code for ribosomal RNAs—molecules that synthesize proteins—since they are some of the oldest, most important genes vital to life itself. Eventually, he found the gene he was looking for: the 16S rRNA gene in prokaryotes (and its equivalent in eukaryotes the 18S rRNA gene). The 16S gene was a fortuitous choice because most of the gene evolves very slowly over time, but there are also variable regions of the gene that happen to mutate quickly [2]. Dr. Woese and his colleagues were able to use the slowly evolving regions as a molecular clock to track relatedness over massive timescales, while the variable regions allowed them to distinguish bacterial strains with genus or species-level precision.

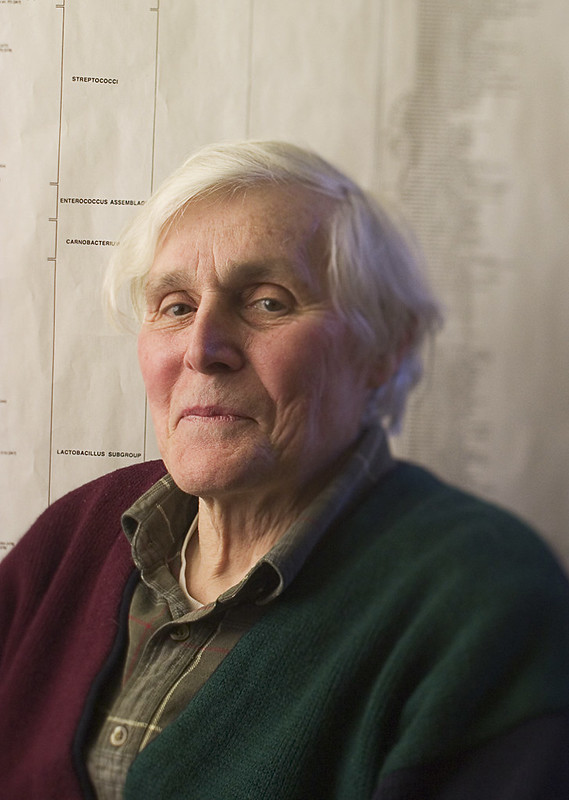

Figure 2. Carl Woese, whose goal to create a tree of all life on Earth using a universal gene changed biology forever. Fun fact: Dr. Woese received his undergraduate degree at Amherst College, right here in Amherst, MA! Image credit: Don Hamerman via Wikimedia Commons.

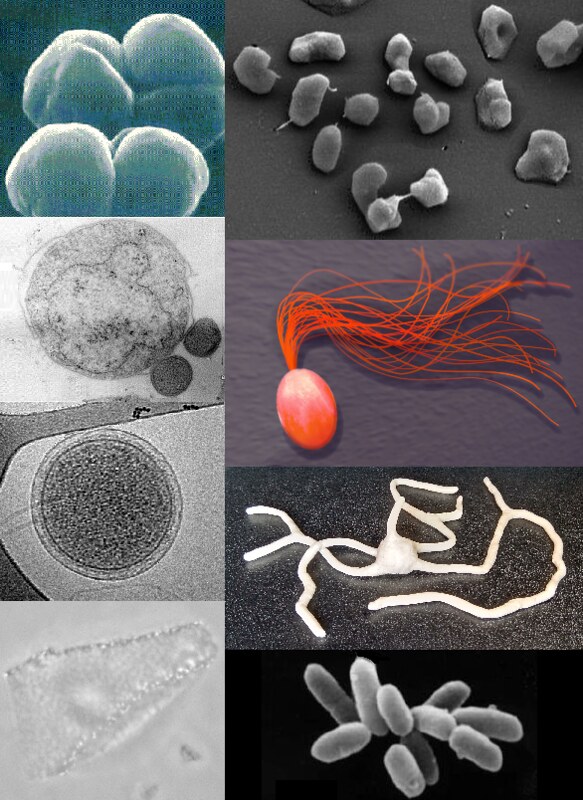

It took Carl Woese and his colleague, George Fox, over a decade to painstakingly sequence parts of the 16S rRNA and 18S rRNA gene across 13 microbial groups [2]. When they compared the sequences to each other, their results were unprecedented: they found that some of the so-called “bacteria” were unlike the other bacterial species in the study and actually clustered into their own distinct group that was more closely related to eukaryotes than to bacteria [5, 6]. This group of microbes often used methane in their metabolisms, had a different cell wall composition than bacteria, and could frequently be found in extreme environments [3, 5]. Carl Woese and his colleagues considered this an entirely new domain of life and named it “Archaebacteria.”

Figure 3. A composite image of different taxa within Archaea, the domain of life first described as Archaebacteria by Carl Woese and George Fox in 1977. Image credit: Maulucioni via Wikimedia Commons.

Carl Woese and George Fox had originally set out to create a more complete tree of life, and in doing so, changed our understanding of the origins and evolutionary relationships of life on Earth. Their results were nonetheless underappreciated at the time of publication, and it would take years for a majority of biologists to accept the conclusions of their research [2,3]. In fact, the full significance of their research wouldn’t be understood until nearly a decade after the publication of these results [7]. Though Carl Woese didn’t know it at the time, he and his team had just pioneered the main method for studying microbial communities (i.e., microbiomes), which has been used to gather much of the data we have on microbial diversity today. Since 1977, these methodological and evolutionary discoveries have allowed for more revolutionary advancements in microbiology and changed our conceptions of life on Earth. What modern discoveries will go on to fundamentally shape the field of biology, as Carl Woese’s did in 1977? Only time will tell.

References:

[1] Fleischmann, Robert D., Mark D. Adams, Owen White, Rebecca A. Clayton, Ewen F. Kirkness, Anthony R. Kerlavage, Carol J. Bult et al. “Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenza*e Rd.” *Science 269, no. 5223 (1995): 496-512.

[2] Arnold, Carrie. The man who rewrote the tree of life. PBS (2014).

[3] Pace, Norman R., Jan Sapp, and Nigel Goldenfeld. “Phylogeny and beyond: Scientific, historical, and conceptual significance of the first tree of life*.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences* 109, no. 4 (2012): 1011-1018.

[4] Stanier, Roger Y., and C. B. Van Niel. “The concept of a bacterium.” Archiv für Mikrobiologie 42, no. 1 (1962): 17-35.

[5] Woese, Carl R., and George E. Fox. “Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: the primary kingdoms.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 74, no. 11 (1977): 5088-5090.

[6] Iwabe, Naoyuki, Kei-ichi Kuma, Masami Hasegawa, Syozo Osawa, and Takashi Miyata. “Evolutionary relationship of archaebacteria, eubacteria, and eukaryotes inferred from phylogenetic trees of duplicated genes.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 86, no. 23 (1989): 9355-9359.

[7] Lane, David J., Bernadette Pace, Gary J. Olsen, David A. Stahl, Mitchell L. Sogin, and Norman R. Pace. “Rapid determination of 16S ribosomal RNA sequences for phylogenetic analyses.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 82, no. 20 (1985): 6955-6959.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- CRISPR technology may be a promising tool to combat multidrug resistant fungus C. auris

- How the search for a universal gene forever changed biology: the story of Carl Woese and 16S sequencing

- Quarantine Blues? The Effects of Social Isolation in the Brain

- The Lovebug Effect

- CRISPR: Careful When Running with Genetic Scissors

- More ›