Eve Beaury OUR ECOSYSTEMS

invasive species biodiversity plant climate change human

3 Reasons Why What You Grow in Your Garden Matters

We often decide what to plant in our gardens based on what looks nice, what is low-maintenance, or what fits into the space we have available. For most, these decisions are pretty easy to make after wandering the aisles of your local nursery or chatting with a landscaper. For invasion ecologists such as myself, these decisions are loaded with more consequences than the average gardener might realize.

Figure 1 A mix of native and non-native plants in a garden outside of Dunvegan Castle, Scotland. (Source: Eve Beaury)

Many backyard plants are non-native, which means they have been moved outside of their historical native range, and have been transported to areas where they do not naturally occur. Although many non-native plants are harmless, they are 40 times more likely to become invasive than native plants, which can have extremely negative consequences for your backyard and beyond [1]. Here are three reasons why being mindful about what you grow in your garden can have a positive impact:

1. Native plants support the birds and the bees

You may have chased bunnies away from your summer veggies or followed a butterfly across your flowers, but have you ever thought about the importance of this backyard biodiversity? Your garden plants provide habitat for many of these critters, and where these plants come from makes a big difference in the biodiversity they support. For example, a study in Pennsylvania found that yards landscaped with native plants supported up to 4 times more caterpillars than yards dominated by non-native plants [2]. It may not seem like an advantage to have caterpillars munching on your garden, but these caterpillars become butterflies that pollinate not only your garden, but plants common in forests, wetlands, or meadows that are a short flight away from your backyard. Caterpillars also provide the primary food source for many backyard birds, which play an important ecological role and add to the ambiance of a backyard garden [2]. Not only do native plants increase food resources for these birds, but the health of some birds is also improved in habitat dominated by native rather than non-native plants [3]. Offering a diversity of native plants in your garden can keep birds healthy and pollinators in high abundance.

Figure 2 The caterpillar of a monarch butterfly munching on native milkweed (of the genus Asclepias). (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

2. Planting native minimizes invasion risk

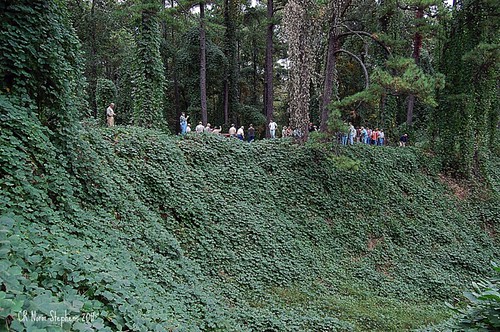

The majority of non-native plants are imported to new areas through the plant nursery industry and marketed for their “rare and exotic” aesthetic value [4]. But the same traits that make these plants desirable for easy gardening, such as large flowers and low-maintenance growth, can also facilitate their dominance of native ecosystems [5]. If these non-native plants escape our gardens, they can reduce biodiversity, restructure habitat, and even impact human health (e.g. Hogweed). Perhaps the best-known example of a detrimental non-native plant is kudzu (Pueraria montana), which is an invasive vine imported to the United States in the 1800s and marketed for its ability to quickly curl along your terraces, giving your garden the appearance of an exotic landscape. Today, kudzu has spread across most of the Southeastern U.S., choking out native vegetation and destroying habitat for native animals. In addition to kudzu, purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii), and the tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima) are other impactful invasive species that were introduced to the United States as garden plants. These species often have native alternatives, such as blue vervain (Verbena hastata) and fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium) that can be planted in place of purple loosestrife.

Figure 3 Kudzu (Pueraria montana) was imported for gardens nearly 200 years ago and is now one of the most impactful invasive species in North America. (Source: Flickr)

3. Gardens as a climate adaptation strategy

Your garden serves as an ecological stepping stone for many plant and animal species to reach larger habitat patches. Climate change is already causing many species to shift their ranges in response to warming temperatures and changing seasonality, and native habitat corridors such as mindfully planted gardens provide resources that facilitate some of this movement. Additionally, many non-native plants brought to the United States arrive from warmer climates [6]. Although these non-native plants are currently restricted to your manicured garden, climate warming may be advantageous for these species if their seeds spread outside of your garden into natural areas. Instead of supporting these warm-adapted, non-native plants that could become invasive, we as gardeners have a chance to adapt to some of the effects of climate change by planting warm-adapted or range shifting native species.

Planting native greatly reduces risks associated with new invasions and slows the importation of non-native plants that could have devastating impacts. Next time you’re picking what to plant in your garden, put some thought into where these species come from and the consequences behind these decisions. To get a headstart on next year’s growing season, check out these resources:

Online guide to choosing native plants in your area: http://plantnative.org/

Bringing Nature Home by Doug Tallamy (http://www.bringingnaturehome.net/)

The Invasive Plant atlas to learn more about invasive species in your area: https://www.invasiveplantatlas.org/

References:

Simberloff, Daniel, Lara Souza, Martín A. Nuñez, M. Noelia Barrios-Garcia, and Windy Bunn. “The natives are restless, but not often and mostly when disturbed.” Ecology 93, no. 3 (2012): 598-607.

Burghardt, Karin T., Douglas W. Tallamy, and W. Gregory Shriver. “Impact of native plants on bird and butterfly biodiversity in suburban landscapes.” Conservation Biology23, no. 1 (2009): 219-224.

Narango, Desiree L., Douglas W. Tallamy, and Peter P. Marra. “Native plants improve breeding and foraging habitat for an insectivorous bird.” Biological Conservation 213 (2017): 42-50.

Lehan, Nora E., Julia R. Murphy, Lukas P. Thorburn, and Bethany A. Bradley. “Accidental introductions are an important source of invasive plants in the continental United States.” American journal of botany 100, no. 7 (2013): 1287-1293.

van Kleunen, Mark, Franz Essl, Jan Pergl, Giuseppe Brundu, Marta Carboni, Stefan Dullinger, Regan Early et al. “The changing role of ornamental horticulture in alien plant invasions.” Biological Reviews (2018).

Liebhold, Andrew M., Eckehard G. Brockerhoff, Lynn J. Garrett, Jennifer L. Parke, and Kerry O. Britton. “Live plant imports: the major pathway for forest insect and pathogen invasions of the US.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 10, no. 3 (2012): 135-143.

Hauser, Mihir Zaveri-Christine. “Giant Hogweed: A Plant That Can Burn and Blind You. But Don’t Panic.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/02/us/giant-hogweed-nyt.html

“Kudzu, Pueraria Montana Var. Lobata Fabales: Fabaceae (leguminosae)”. EddMaps. https://www.eddmaps.org/Species/subject.cfm?sub=2425

More From Thats Life [Science]

- La Belle et La Boeuf (NOT!) How do human meat preferences impact climate change?

- Artificial Selection: From Tiny Fish to Empty Dish

- A breath of fresh air: How the great oxygenation event changed life on Earth forever

- The Women Behind the Gun vs. The Women Behind the Bird

- How Community-based Conservation Helps Lemurs

- More ›