Grace Pold GRAD SCHOOL DIARIES

women in science climate change collaboration

Standing on the shoulders of giants

Fig. 1 - The original “standing on the shoulders of giants” didn’t mean the same then as it did today. In Greek mythology, the sighted servant Cedalion stood on his blind master giant Orion, helping him see. Now, it is not the giants but us who would be blind without them, (Source: Library of Congress via Wikipedia)

Like pretty much all scientists, the research I do builds heavily upon those who came before me.

I mean, how would 21st-century NASA have sent a rover to Mars if Katherine Johnson hadn’t done all those complex calculations to get the first successful space missions off the ground in the 20th century? Or if they hadn’t had Margaret Hamilton’s software to land their first mission on the moon? Or how would we have new and better antimalarials if Tu YouYou hadn’t re-discovered and isolated some of the earliest effective treatments? In turn, would she have had such success identifying this effective medicine if generations before had not been so rampant with their development of herbal remedies? Where would our knowledge of how fast antibiotic resistance can spread be if Esther Ledenberg hadn’t uncovered a range of methods by which bacteria share genes?

My own science, however, depends on the work of a scientist by the name of Maud Menten. Until recently, she was just a name to me – actually, a parameter (number) in an equation.

Fig. 2 - Maud Menten. (source: Smithsonian Institution via Wikipedia)

Dr. Menten is so much more than a name or a number. Born in Ontario in 1879, Maud graduated with two bachelors and a medical degree from the University of Toronto at a time when few if any women got PhDs in medicine. She then moved to work at the Rockefeller Institute in New York, where she completed some of the earliest studies examining the effects of radiation on cancerous tumors. Subsequently, Maud began to look at the effect of anesthesia on blood pH which got her in contact with Leonor Michaelis. Ultimately, this intellectual partnership with Michaelis would lead to the development of one of the best-known equations in biochemistry.

Her work didn’t stop there though; she returned to the US, got her PhD at the University of Chicago, and went on to publish a hundred or so papers covering everything from DNA abnormalities associated with cancer to the successes and failures of antibiotic treatment for pneumonia. In the process, she developed a number of the techniques still used in labs today,. Among them, protein electrophoresis, upon which we have built a substantial chunk of our current knowledge of how the human body works.

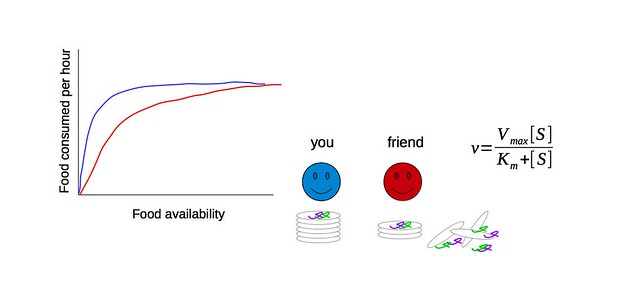

So what about this famous equation then? As an example, imagine you are sitting with a bunch of your friends at an all-you-can-eat restaurant where the food comes by on a conveyor belt. If there is only one chef on duty, then food comes by so slowly that you have no problem eating it all, and there is a long wait between plates. As more chefs come on duty, the food comes by faster, and you spend a greater fraction of your time eating and a smaller fraction waiting. Eventually, there are so many plates coming by so fast that you can’t swallow before the next lot of food comes by. You literally cannot eat any faster, no matter how much food comes by. At this point, your rate of consumption is saturated. The Michaelis-Menten equation describes the relationship between the maximum rate of consumption and the food supply (“substrate concentration”) at which half of the maximum rate of consumption occurs. We call the maximum consumption rate “Vmax”, and the food concentration when half the maximum consumption rate occurs “Km”.

Now imagine you have a clumsy friend who can eat as fast as you once he gets the plates off the carousel (same Vmax), but he drops half of them. Under this scenario, he would need twice as many plates of food in order to eat as fast as you (higher Km). This makes him a bit of an inefficient eater!

Fig. 3 - Michaelis-Menten kinetics. In blue - you. In red - your clumsy friend. The maximum consumption rate (Vmax) of you and your friend is the same, but he needs a higher concentration of food in order to eat as fast as you. Therefore, his Km - the Michaelis-Menten (or half saturation) constant - is higher than yours. The Michaelis-Menten equation appears to the right and can be fit to the data using the Vmax and Km for you and your friend: v = consumption rate; Vmax = maximum rate at which you could consume food given an unlimited supply of it (rate of enzyme catalysis); [S] the concentration of food (substrate). (source: Grace Pold)

I routinely use the Michaelis-Menten in my work to look at how soil bacteria behave when different kinds and concentrations of decomposing leaf litter are available. If I add a very high level of substrate for the microbes, I can estimate how large the pool of enzymes the microbes use to break down the litter is. But since there is rarely if ever an unlimited supply of food available for microbes, it is generally more useful to add a range of substrate concentrations and see how the activity changes, fitting the Michaelis-Menten equation to the data. Then we can infer how fast the microbes are actually able to access the food in the soil. The amount of food available decreases when we subject soil to a climate change simulation [1], and both the maximum rate of consumption and the concentration at which half maximum consumption occur may also decrease [2]. Therefore, using the Michaelis-Menten equation helps us predict how fast microbes can grow, which kinds are growing best under different conditions, and how fast we can expect soil carbon to be lost with climate change.

So there you have it: one little equation, two scientists, and the power to infer a lot of important conclusions.

References

Pold, Grace, A. Stuart Grandy, Jerry M. Melillo, and Kristen M. DeAngelis. “Changes in substrate availability drive carbon cycle response to chronic warming.” Soil Biology and Biochemistry 110 (2017): 68-78.

Wallenstein, Matthew, Steven D. Allison, Jessica Ernakovich, J. Megan Steinweg, and Robert Sinsabaugh. “Controls on the temperature sensitivity of soil enzymes: a key driver of in situ enzyme activity rates.” In Soil enzymology, pp. 245-258. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010.