“John Swenson” EARTH'S ORGANISMS

human fish mammal evolution

You are a fish

Scientifically, you and I are fish [1].

Sounds strange.

It becomes less strange when we critically examine the implicit guidelines we use to intuitively distinguish a ‘fish’ from a ‘non-fish’ on a day-to-day basis. Let’s scrutinize these criteria more closely to see if the idea that humans are fish is as preposterous as it sounds.

Implicit Criterion 1: All fish have fins

If the presence of fins is a defining feature of a fish then we need to define what a ‘fin’ actually is, and what distinguishes a ‘fin’ from a ‘limb.’ Unfortunately, the boundary between fins and limbs is a bit convoluted.

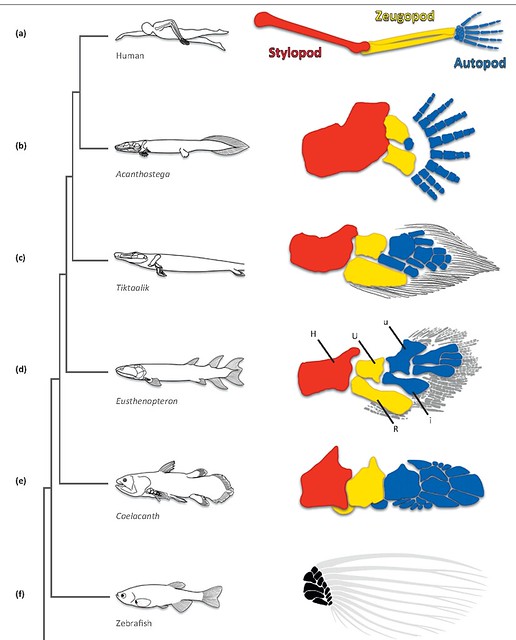

Fins vary greatly in structure. Zebrafish fins, for instance, are light and flexible, appearing as translucent sheets supported by thin rods. Coelacanth fins, on the other hand (no pun intended), are robust and sturdy, appearing more similar in structure to human limbs than fish fins. So physically, some fins are more limb-like than fin-like. Meanwhile, the molecular mechanisms that underlie the development of fins and limbs are remarkably similar [2-4].

If we can’t really distinguish a fin from a limb physically or molecularly, then what is a fin, exactly?

Turns out, that’s the type of philosophical question that is best discussed over a beer. For now, it would seem the boundary between fins and limbs is a bit fuzzy, so let’s see if we can find another benchmark that we can reliably use to identify a ‘fish.’

Fig 1. The fins of fish like coelacanths possess bony structures similar to the upper arm, forearm, and hand/wrist of humans. In other words, coelacanth fins (2nd from bottom) resemble human limbs (top) more than fins of other fish, like zebrafish (bottom). (Source: Schneider and Shubin 2013).

Implicit Criterion 2: All fish have gills and breathe water

Gills. Water-breathing. The most fish-like characteristics there are…

…don’t apply to lungfish. Though lungfish technically have gills, in most species the gills do not take in oxygen, but are used only to expel carbon dioxide [5].

In contrast, a tadpole lives in water and breathes with gills before developing lungs and growing into a proper frog. As an adult, a frog maintains the capacity to breathe water, it just breathes through its skin rather than using gills. So, is a frog a fish without gills? Tadpoles have gills … are they fish?

Also, crabs. Crabs and other invertebrates have gills. Should we count them as fish?

Let’s say fish need to have gills, breathe water *and *have a backbone. That means crabs are not fish…but tadpoles still are. Lungfish may or may not be, depending on whether carbon dioxide expulsion alone is sufficient to classify them as “breathing water.”

It seems the line between a fish and a non-fish is a little blurred. Maybe it would be easier to define a fish based on what it does NOT do…

Fig 2. This is a lungfish. It’s a fish (with lungs) that exhales with its gills and inhales with its lungs. Yes, this is a real thing (Photo credit: jan.stefka).

Implicit Criterion 3: Fish definitely do NOT breathe air

Lungfish? Yeah, those problematic buggers inhale air and use it for metabolic purposes. But they’re not the only fish that do this: tarpon breathe air as well. In fact there are quite a few amphibious fish that can easily breathe air and live out of water for days (or weeks) at a time (many even have ‘fins’ that they use to walk, further blurring the demarcation between fins and limbs). So we cannot use air-breathing as a criterion either.

The evolution of air-breathing in fish exemplifies why it can be so difficult to draw a definitive line between which vertebrates are fish and which are not: reliable criteria are hard to come by because water-dwelling and land-dwelling vertebrates share many traits that have a common evolutionary origin, for instance swim bladders and lungs.

A swim bladder, generally, is a sac of air that helps fish maintain their buoyancy underwater. It’s an internal balloon that expands and contracts in response to changing pressure in the ambient water. In some fish, the swim bladder is connected to the gut, allowing it to gulp air at the surface to voluntarily adjust buoyancy. Evolutionarily, it would have been beneficial to have a structure like this for fish that live in low-oxygen waters, because the swim bladders could double as respiratory organs. However, fish in oxygen-rich waters wouldn’t have needed swim bladders for respiration because their gills could extract enough oxygen from the environment to meet metabolic demands. In these fish, the swim bladder would have been free to specialize in buoyancy and disconnect from the gut over time. For fish that didn’t live in water at all, the swim bladder would have needed to adopt respiration as its primary function (since gills don’t work in air). As it became increasingly specialized, the swim bladder eventually evolved into what we now call lungs. Yes, lungs are modified swim bladders [6] that specialize in extracting oxygen from air for metabolic purposes.

The swim bladder/lung and fin/limb relationships show that it is difficult to draw a hard line between a fishy trait and a non-fishy trait, and this makes it hard to set logical standards by which we can discern a ‘fish’ from a non-’fish’. Perhaps it would be more parsimonious to conclude - as evolutionary biologists have - that land-dwelling vertebrates (including humans) are fish. We just walk around on modified fins and breathe air with revamped swim bladders…no wonder humans can be so awkward. We are, literally, fish out of water.

References

Betancur-R, Ricardo, Richard E. Broughton, Edward O. Wiley, Kent Carpenter, J. Andrés López, Chenhong Li, Nancy I. Holcroft et a*l. “The tree of life and a new classification of bony fishes.” PLoS current*s 5 (2013).

Nakamura, Tetsuya et a*l. “Digits and fin rays share common developmental histories.” Natur*e 537.7619 (2016): 225.

Yano, Tohru, and Koji Tamura. “The making of differences between fins and limbs.” *Journal of anatom*y 222.1 (2013): 100-113.

Schneider, Igor, and Neil H. Shubin. “The origin of the tetrapod limb: from expeditions to enhancers.” *Trends in genetic*s 29.7 (2013): 419-426.

Johansen, Kjell, and Claude Lenfant. “Respiration in the African lungfish Protopterus aethiopicus: II. Control of breathing.” *Journal of Experimental Biolog*y 49.2 (1968): 453-468.

Longo, Sarah, Mark Riccio, and Amy R. McCune. “Homology of lungs and gas bladders: insights from arterial vasculature.” *Journal of Morpholog*y 274.6 (2013): 687-703.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- Freshwater Mussels are Declining: Why Should You Care, and What Can You Do?

- The Story of Chestnuts in North America: How a Forest Giant Disappeared from American Forests and Culture

- Friendships, Betrayals, and Reputations in the Animal Kingdom

- Why Don't Apes Have Tails?

- Giant Bacteria, Giant Genomes

- More ›