“Alison Fowler” HOW IT WORKS

genetics cells health medicine zoology

It’s Not Science Fiction, Chimeras Are Real

In 1953, a 25-year-old woman known as Mrs. McK went to the doctor to get some standard blood work done. You can imagine the shock she experienced when the doctors notified her that her blood was 39% type O and 61% type A-. Our understanding of blood type inheritance states that each of us should have just one blood type. What was going on here?

Based on previous accounts of male traits popping up in female cows that were born with twin brothers, the doctors hypothesized that sharing a womb might mean more than just sharing a birthday for some animals. So Mrs. McK was further shocked when the doctors asked if she had a twin. She replied that yes, she had a twin brother who died at age 3 from pneumonia. It turns out that, like in twin cows, the woman and her twin brother exchanged cells early in their development, which led to the permanent establishment of his genome in parts of her body [1]. Similar studies over the last few decades have shattered and rebuilt our understanding of genetics, development, and identity.

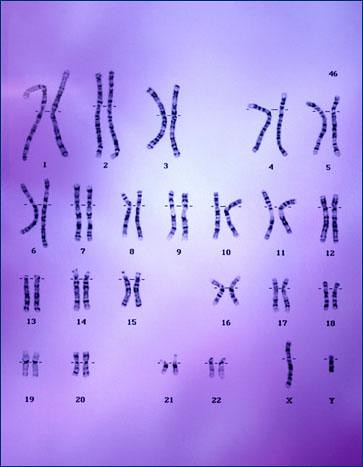

This phenomenon of multiple genetic identities commingling in one organism is called genetic chimerism and challenges our biological and social labels. There are many ways that chimeras can be formed, including two fraternal twin embryos fusing in the womb, mothers receiving stem cells from her developing fetus, errors in cell division, and organ or bone marrow transplants. Like the example above, some of these processes result in organisms with ambiguous sex. Mrs. McK, for instance, had some Y chromosome-bearing cells (Fig. 1). But does this make her a “man?” This question clearly doesn’t have a yes or no answer and many factors influence gender association and identity, not just the number of Y chromosomes (at least in humans). Every day, we learn how difficult it can be to categorize nature; many of our black and white labels need to be revisited.

Fig 1. A typical male human karyotype (visual appearance of the chromosomes in any given cell). This karyotype has one X and one Y chromosome, while the karyotype of a typical female would have two X chromosomes. (source: Renee Diamond)

When we think about what defines an individual’s sex, there are countless examples in the animal kingdom where the lines are blurred. Consider the deep-sea angler fish (Fig. 2). Swimming a mile below the surface in complete darkness, some angler fish have an unusual mating process. Since encounters between individuals are so incredibly rare, they get a bit attached when they do find each other. Like really attached. Male angler fish, just a fraction of the size of the females, literally attach themselves to the skin of the female. The male exudes an enzyme that dissolves the barrier of skin between their bodies, allowing them to share blood vessels, and the two fish become one chimera. How romantic!

We are taught that humans, along with most other animals, develop through the fusion of two cells, one from each parent. These two cells contain half of the genetic information from each parent, which neatly combine to form one full set of chromosomes. This mixture of genes produces a new, unique combination of traits, leading to the wonderful diversity we see in the world. And yet, there are many other potential routes for this process to take, which add even more diversity to earth’s organisms. Chimeras are one of many fates of gametes (eggs and sperm), genes, and developing cells, and scientists are learning how surprisingly common these occurrences are [3]. While these chimeras might be exceptions to the rule, they are still nature’s way of producing new life and diversity, and every example, no matter how seemingly-bizarre, deserves appreciation.

Fig 2. A female angler fish (Photocorynus spiniceps) with a tiny male attached to her back. The mates become one chimera when the skin separating them dissolves and they begin to share blood vessels and nutrients. (Photo credit: © Theodore W. Pietsch, used with permission of the photographer)

References

[1] Dusnford I, Bowley CC, Hutchinson AM, Thompson JS, Sanger R, and Race RR (1953) A human blood-group chimera. The British Medical Journal. 2(4845):1103.

[2] Pietsch TW (2005) Dimorphism, parasitism, and sex revisited: modes of reproduction among deep-sea ceratioid anglerfishes (Teleostei: Lophiiformes). Ichthyollgical Research. 52(3):207-236.

[3] vanDijk BA, Boomsma DI, and de Man AJM (1996) Blood group chimerism in human multiple births is not rare. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 61:264-268.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- CRISPR technology may be a promising tool to combat multidrug resistant fungus C. auris

- How the search for a universal gene forever changed biology: the story of Carl Woese and 16S sequencing

- Quarantine Blues? The Effects of Social Isolation in the Brain

- The Lovebug Effect

- CRISPR: Careful When Running with Genetic Scissors

- More ›