Emma Dauster HOW IT WORKS

eye pigmented epithelium evolution neurobiology

Human Eye Structure Makes No Sense…Or Does It?

Visual information is processed first at the back of the eye, then travels back out toward the lens where it was taken in.

Wait, that makes no sense.

The human eye is a classic example of backwards anatomy through convoluted evolution. In the process of evolution, random mutations occur in an organism which may be either advantageous or disadvantageous. Then the advantageous mutations are selected for while the disadvantageous mutations are selected against, meaning that individuals with random qualities that make them more desirable (like opposable thumbs) are more likely to mate and propagate the feature to future generations. But these “complete” features rarely evolve completely at once, instead showing a bit of a meandering path with incremental improvement. Eventually these features become more ubiquitous than not for the species. This means that we often end up with systems that don’t work the way you might envision had someone sat down and created the perfect structure for a particular function, but they work nonetheless.

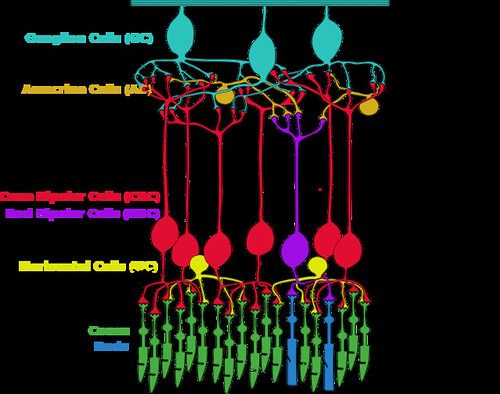

Usually whenever someone wants to give support for the physiological imperfection brought about by evolution, they criticize the eye. In the human eye, we have rod cells which mainly process light and dark information, situated next to cone cells which mainly process color information. The rods and cones are lined up next to one another at the back of the eye with horizontal cells taking information from neighboring cells to facilitate intercellular communication. This helps us form a complete picture including both color and light aspects of the visual scene in front of us. Information is then sent from rods and cones to bipolar cells situated in front of them, integrated again by amacrine cells (similar to horizontal cells) and ganglion cells (similar to bipolar cells). At each step, the visual information travels in a convoluted path back out toward the lens where it was taken in, but why would it have evolved that way?

Why would information travel all the way through the eye, past all these neurons, and start processing in the very back? We take in visual information at the back of the eye, feed it forward, and send it back again to get to the brain for further processing. Surely it would make more sense to have the rods and cones closer to the lens so that information is sent directly back in a straight line instead of the convoluted path it actually takes. This is why the eye is such a common example of the perfect imperfection that is the human body. If we were created to function optimally, this pathway would be more direct.

Figure 1. Part of the pathway to process visual information in the human eye. Rods and cones send information to bipolar cells and then to ganglion cells, then through the optic nerve into the brain. Visual information comes from beyond the top of this image at the lens, straight to the bottom where the rods and cones are, processed back up to the top where the ganglion cells are, and back beyond the bottom to the brain. (Source: Timtammittee, wikimedia commons)

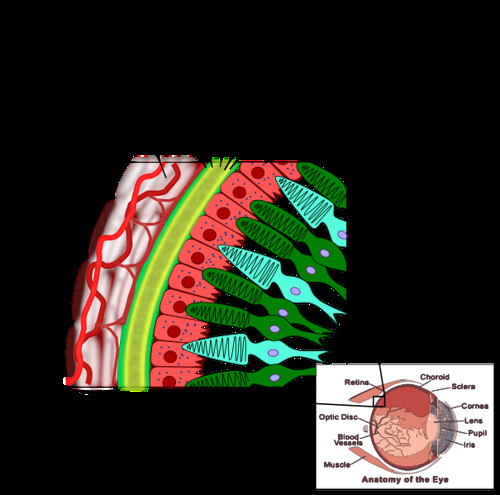

There would have to be a pretty good reason for the pathway to be so backwards, and it turns out there is. It’s called the pigmented epithelium. Rods and cones have rhodopsin receptors in the outer segments of the cells (the part of the cell shaped distinctly, from which they got their names). This receptor, embedded in the membrane of disks indicated by the squiggly lines in Figure 2, is activated by photons. Rhodopsin is so sensitive that it can detect a single photon! However, it needs a cofactor called 11-cis-retinal to function properly. You get 11-cis-retinal from vitamin A in carrots, which is why people say eating carrots is good for your eyesight. Light changes 11-cis-retinal into 11-trans-retinal and that starts the signal that gets sent from rods and cones through the pathway described above. Once all of the 11-cis-retinal is converted to 11-trans-retinal, rhodopsin can no longer respond to incoming photons and your receptor is bleached. The pigmented epithelium is very important at this point. Without the next step facilitated by the pigmented epithelium, we would be blind after one exposure to light. The retinal pigment epithelium converts 11-trans-retinal back into 11-cis-retinal so that we can respond to the next light signal and our receptors do not remain bleached.

We need the pigmented epithelium to be close to rods and cones because proteins within it recycle 11-trans-retinal for continued use as 11-cis-retinal. Additionally, when membranes and proteins in rod and cone outer segments get worn out, the pigmented epithelium absorbs them so that new membranes and proteins can be used in their place for optimal function of these photon sensitive cells. The pigmented epithelium also provides oxygen to your rods and cones. It is, therefore, a critical structure in your ability to see and process the visual scene around you.

Figure 2. The pigmented epithelium lines the back of the eye, situated behind the rods and cones. (Source: Egmason, wikimedia commons)

Now we know why rods and cones have to be next to the pigmented epithelium, but why do they have to be in the back of the eye? Well, the pigmented epithelium gets its name because it’s dark. In addition to all of the critical functions mentioned above, it is dark to prevent light scattering when it comes through your eye and to absorb photons for decreased photo damage. If this dark structure were not at the back of the eye, it would block light from getting to your receptors. They would not be able to respond to photons and do their job in allowing us to process the visual world.

The pigmented epithelium serves a critical role in rod and cone function and must be close to them. It also must be in the back of the eye. Therefore, light information must travel the convoluted path to the back of the eye and feed forward to then be sent back to the brain.

This path is actually quite elegantly set up, contrary to how it seems at first. There is still a ton of support for evolution in convergent and divergent structures, so all of this is not to say that the structure and function of the eye proves evolution false (we still have a blind spot, after all.) Rather, the moral of this story is that there is often a reason for things that at first do not seem to make sense. We just need to be persistent in figuring out what that reason is and it will reveal itself to be far more complex than we could have imagined before.

References:

[1] Young, R. W. 2003. “Evolution of the human hand: the role of throwing and clubbing.” Journal of Anatomy, 202(1), 165–174.

[2] Jensen lecture at University of Massachusetts, Amherst. (Using Kandel, Principles of Neural Science Fifth Edition. 2013.) December 5, 2017.

[3] Cowell lecture at University of Massachusetts, Amherst. (Using Kandel, Principles of Neural Science Fifth Edition. 2013.) February 5, 2018.

[4] Zhao L, Wang Z, Liu Y, Song Y, Li Y, Laties AM, Wen R. 2007. “Translocation of the retinal pigment epithelium and formation of sub-retinal pigment epithelium deposit induced by subretinal deposit.” Mol. Vis. 13:873-80.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- CRISPR technology may be a promising tool to combat multidrug resistant fungus C. auris

- How the search for a universal gene forever changed biology: the story of Carl Woese and 16S sequencing

- Quarantine Blues? The Effects of Social Isolation in the Brain

- The Lovebug Effect

- CRISPR: Careful When Running with Genetic Scissors

- More ›