Emily Fusco GRAD SCHOOL DIARIES

invasive species grass field work wildfire

The Tale of A Conspicuous Invader and Inconspicuous Field Sites

We’ve talked a lot about invasive species on That’s Life Science. You may remember them from such posts as “Invasive Species And Invasion,” “Are We Running Out Of Invasives,” or “How An Invasive Plant Helped Fuel The Largest Wildfire You’ve Never Heard Of.” These species are some of the big baddies of the global change world, causing damage to both ecosystems and economies. Invasive plants in particular are known for growing unabashedly, outcompeting native species, and in some cases creating vast monocultures (Fig 1).

Figure 1. These invasive species (left to right) cheatgrass, kudzu, and Melaleuca form monocultures in their invasive ranges. Image credits: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Galen Parks Smith, Forest and Kim Starr.

One invasive plant, Burma reed (Neyraudia reynaudiana) is of particular interest to me because of my work on invasive grasses and fire. I went to Florida recently to scope out some potential field sites where we could sample this notorious invasive. Burma reed is originally from Asia, but also flourishes in southern Florida[1]. It is particularly problematic in Pine Rockland ecosystems where it provides fine flammable fuel and promotes fire beyond what is natural [2], which is pretty impressive considering fire burns frequently in many pine ecosystems. The increased fire frequency in these systems can kill the native vegetation.

Given that invasive plants often grow conspicuously, and Burma reed in particular can easily grow more than 10 feet tall, I thought that finding some potential field sites for sampling would be relatively simple. So I traveled to southern Florida where this grass is known to invade, and quickly found some Burma reed in and around Everglades National Park [Fig. 2]. It just wasn’t exactly where I needed it to be.

Figure 2. Burma reed with a 6 foot tall man (and NO pine trees) for scale. Image credit: Emily Fusco

It may seem strange that I needed this invasive species to be anywhere, considering most people would be happy to see no invasives at all, but let me explain. For some upcoming work, we are hoping to compare native pine systems with no Burma reed to pine systems that have been converted to Burma reed. By pairing invaded sites with adjacent native sites, we can most effectively look for differences in carbon storage between the sites. If the two sites are close together, it is likely that any differences in carbon storage between them are because of the Burma reed invasion, as opposed to other factors like elevation, differences in rainfall, temperature, etc.

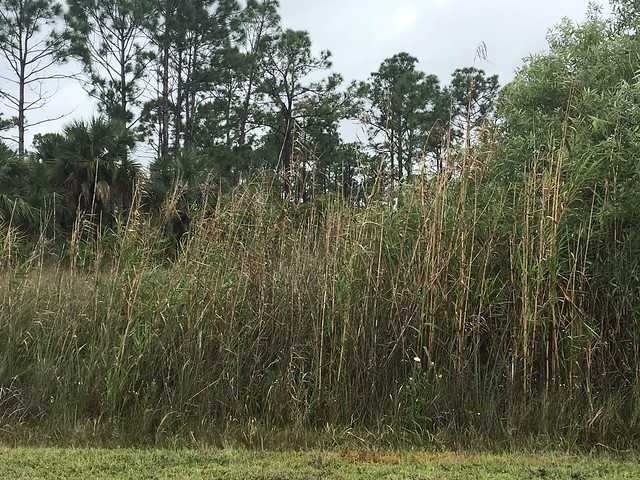

Unfortunately, the only Burma reed I could find anywhere close to the native pine systems was growing in roadside drainage ditches (Fig 3.) This is problematic for my research because these roadside ditches are not likely very similar to the adjacent pine systems. Frustrated, I spent time trying to track down potential field sites from a nearly twenty year old paper [2] and using EDDMappS (an invasive species database), to find leads. After many days of searching, I came up empty-handed and came to the realization that it was going to take a lot more than cruising around southern Florida to figure out where any sampling would need to take place. Instead, I would need to rely on the goodwill of researches and land managers alike to direct me to these hidden patches of Burma reed. Let the emailing begin!

Figure 3. Burma reed growing in a roadside ditch at Big Cypress National Preserve. Image Credit: Emily Fusco.

References:

[1] Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Neyraudia reynaudiana. Accessed April 6, 2019.

[2] Platt, W. J., & Gottschalk, M. (2001). Effects of exotic grasses on potential fine fuel loads in the groundcover of south Florida slash pine savannas.* International Journal of Wildland Fire*, 10, 155–159.