Emma Dauster HOW IT WORKS

neuroscience brains surgery

Brain Surgery… It’s Not Rocket Science!

I performed my first brain surgery at age 19. I’m a neuroscientist, but the less you know about what I do every day, the more impressive it sounds. I perform brain surgery…on rats. And then for the next six months I train them to perform operant tasks, while getting peed on most days cleaning up after them. (The operant task involves pressing a lever to get sugar-water, so they will perform hundreds of self-initiated trials every day.) The life of a rodent brain surgeon isn’t as luxurious as it sounds.

Disclaimer: I have gone through training in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at each institution at which I have conducted brain surgeries to ensure that they are ethical and sterile with the best outcomes for the animals in mind. This procedure is never to be followed without express approval by your IACUC.

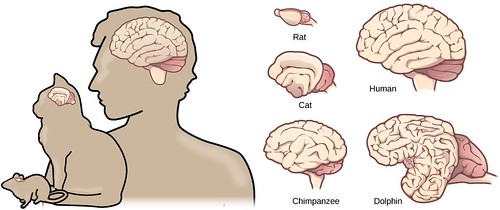

Rodent brains are closer to human brains than a lot of people realize. The fact of the matter is that humans and rats are both mammals. While our brains might look very different, the similarities in structure and function are remarkable. There are structurally and functionally similar brain regions in humans and rats, for completion of tasks such as sensory signal processing, decision-making, and accessing memories. Just look rearward from the big wrinkle a little bit, over a smidge, and you reach the same neural center in humans and in rodents. It can’t be that simple… can it?

Figure 1. Comparative physiology of various animal brains. There’s a little variety but overall they are much more similar than you might have thought. (Source: CFCF Wikimedia commons)

Actually, that’s how brain surgery works. Okay, the directions are a little more specific, but not by *that *much. We use sutures (the lines where bones in the skull join together) as landmarks to orient ourselves when finding specific brain regions underneath. Every skull has the top line (bregma), middle line (midline), and bottom inverted V (lambda) that the brain surgeon can use to locate their surgery site. For example, to find the main source of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine to the brain (located in the brainstem), you make sure the skull is flat by measuring 0 mm change from bregma to lambda, then measure back from bregma 9.5 mm, to the left or right 1.3 mm, and down 6.5 mm. These are example coordinates from the female rat brain, but a similar procedure can be followed in other organisms.

Figure 2. Looking down at a skull from above, the nose would be at the top of the figure and ears on either side. This image displays the coronal suture or bregma, sagittal suture or midline, and lambdoid suture or lambda. (Source: Johannes Sobotta, CFCF Wikimedia commons).

Many scientists before me have performed surgeries and experiments to determine which coordinates generally regulate which chemical, physiological, and behavioral changes in the animal, so I can be confident in my surgery. I still confirm the surgery location after the fact in case the skull was not perfectly flat when I measured the coordinates, but I have found this method to be incredibly reliable. Brain atlases such as the Allen Brain Atlas are available for anyone to look through and determine the location of their region of interest [2]. It is important to consider that there may be different coordinates depending on the sex of your subject, which is the case in Long-Evans rats where the females are smaller than males, but other than that a rat is a rat is a rat.

Ultimately, there is so much that we don’t know about the brain because until relatively recently, tools were far more invasive. You could give someone a lobotomy or take advantage of rare case studies such as Phineas Gage in which an accident led to brain damage, but there were no reversible procedures for surgeons to utilize [5]. Once a surgery was conducted, the patient would never be the same. This is not the case today.

Figure 3. This depiction of a lobotomy to inactivate certain brain regions has many similarities to how we currently conduct brain surgeries. Today, we are much more precise. (Source: Jill Robidoux, flickr)

The Mutter Museum has some interesting lobotomy-related items such as Figure 3. As far as lobotomies go, there is substantial social stigma regarding the procedure. In some cases, the lobotomy does not have its desired effects and even has adverse effects. However, there are a lot of similarities between the lobotomies of the past and our current brain surgeries. As in Figure 3, the individuals performing lobotomies appear to have utilized coordinates relative to the midline to determine where their region of interest sits. They would then destroy that brain tissue and see if the negative behavior disappeared. As I described earlier, brain surgeries today also utilize a coordinate system and we also render those regions dysfunctional. However, our current coordinate system uses measurements down to a fraction of a fraction of a centimeter compared to the older general brain region target, so we can be much more specific than before. We also have technology today to render a specific brain region (or even specific cells within a brain region) TEMPORARILY inactive. Two examples of these techniques are called optogenetics and DREADDs, or designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs [3,4]. Of course there are still a huge amount of regulations when it comes to surgery on humans, so this new technology has not yet reached clinical use. But in my rodent surgeries they act totally normal after waking up from surgery and do not change their behavior until I temporarily inactivate the neurons that I targeted in surgery. More modern temporary inactivation through optogenetics and DREADDs remedies the permanence problem of older brain surgery techniques. In both of these techniques, all brain tissue remains intact and the neuronal activity is disrupted in a reversible manner using either a flash of light or a shot. Check out the sources at the end of this post for more details on the chemistry and genetics involved in these manipulations [3,4].

But in 2019, we still resort to removing large chunks of the brain in extreme cases such as drug-resistant epilepsy [1]. Your brain is so resilient and adaptable that the remaining neurons will often compensate for the newly missing tissue and take on extra responsibilities so that you can still perform all of the same daily tasks that you did before the surgery. Though this doesn’t always happen, surgeons resort to these extreme measures because there is still so much that we don’t know about the brain. What we do know is that sometimes those surgeries solve life-threatening problems. The studies that researchers like me conduct help to develop better treatments than brain tissue removal, but there is still so much to learn.

Brain surgery: it’s not as difficult as it is mysterious.

References:

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER) (1998-2019)

Deisseroth, K. (2011). Optogenetics. Nature Methods, 8, 26-29.

Roth B. L. (2016). DREADDs for Neuroscientists. Neuron, 89(4), 683–694. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.040.

O’Driscoll, K., & Leach, J. P. (1998). “No longer Gage”: an iron bar through the head. Early observations of personality change after injury to the prefrontal cortex. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 317(7174), 1673–1674. doi:10.1136/bmj.317.7174.1673a.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- CRISPR technology may be a promising tool to combat multidrug resistant fungus C. auris

- How the search for a universal gene forever changed biology: the story of Carl Woese and 16S sequencing

- Quarantine Blues? The Effects of Social Isolation in the Brain

- The Lovebug Effect

- CRISPR: Careful When Running with Genetic Scissors

- More ›