Emma Dauster HOW IT WORKS

brain fat myelin white matter

Fat is Good for Your Brain

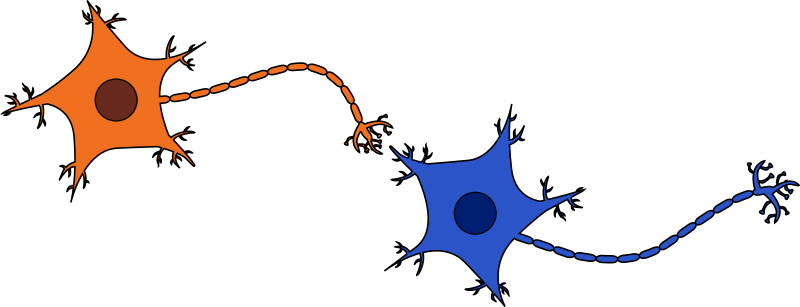

Your brain, like the rest of your body, is the collection of many cells. So what? Everything is made of cells. But the cells in your brain communicate with each other in a unique way, facilitated by fat. Neurons are very similar to trees, with one end that branches out into what are called dendrites that absorb as many chemicals as possible like the roots of a tree. Those chemicals flow through the cell body and then down an axon: a long segment similar to the trunk of a tree. Finally, they are released through branches at the end of the axon, called the axon terminal, like the branches of a tree. Neighboring neurons can then absorb the chemicals that the last neuron just released through their own dendrites, then down their axon, and out their own axon terminal to the next neuron. This process occurs almost instantaneously. And it can go even faster if it’s covered in fat!

Figure 1. Neurons send information to each other from one end of the cell to the other. Chemicals are picked up at the dendrites and released at the axon terminal for another neuron to pick them up at the dendrites, and so on. Source: Dana Scarinci Zabaleta, Wikimedia commons

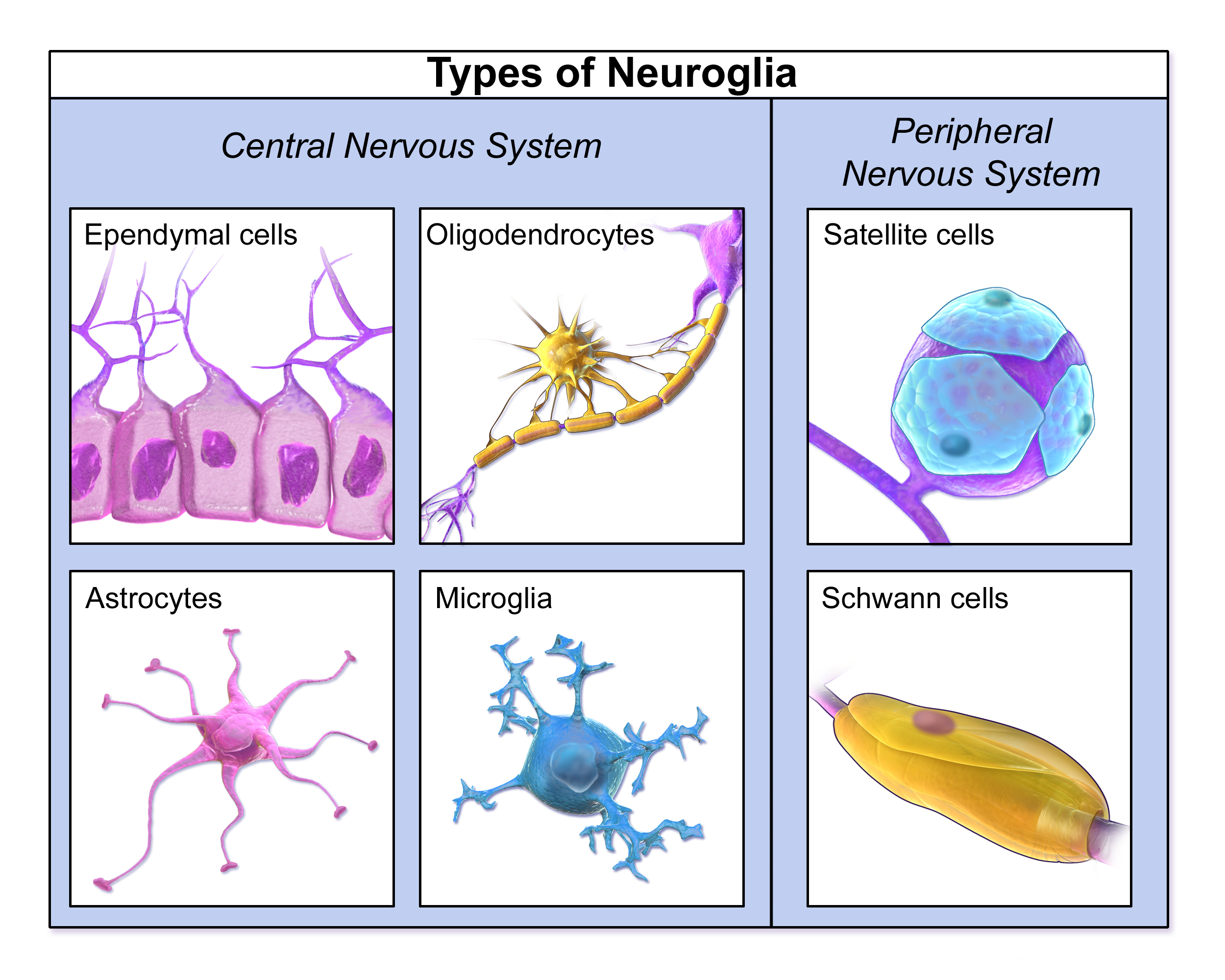

How does covering a neuron in fat make the message travel to the next neuron faster? Imagine you’re walking along a path. Every step you take only gets you a little bit farther along that path. What if you started taking big jumps forward instead of small steps? That’s what fat allows information to do as it travels down the axon. A cell that’s operating at maximum speed can get up to 268 miles/hour thanks to that fat [2]! Some neurons have fat surrounding small segments along the axon, so that a signal can jump between the fat segments and travel faster than walking along the entirety of the axon. Just to drive the point home, the giant squid has a massive axon with a 500 millimeter diameter, while the frog has a much smaller axon with a 12 millimeter diameter. Both of these axons send information at 25 meters/second, despite the squid axon taking up 1,500x more space and 5,000x more energy than the frog axon [1]. These axons operate at the same speed because the frog axon is covered in fat. This is called a myelinated axon. Myelin is made of lipids and proteins that come from “supporting” cells such as oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells [1]. These are examples of glial cells, which are not neurons but interact with them [Figure 3].

Figure 2. The myelin sheath covers most of a neuron’s axon, allowing signals to travel much faster than those on unmyelinated axons. Source: Dhp1080, Wikimedia commons

The brain cells that most people think about are neurons, which send and receive chemical and electrical messages to produce thoughts and actions. A lot of people like neurons for their diversity. They can be roughly as short as 0.1 millimeter or as long as 1 meter [3], and can have just a few branches or many branches in their dendrites. Historically, scientists conducting experiments to determine the root of different behaviors from leg spasms to attention deficits have focused on neurons. It is a nice starting point to work with linear cells that send information in one direction. A lot of knowledge has come from (and continues to come from) studies about which neurons communicate with which other neurons. This information is often gained by looking at how close the dendrites of one neuron are to another neuron’s axon terminal to see the flow of information throughout the brain. There are about 100 billion neurons in the brain. However, neurons are a relatively small portion of the cells in your brain. Glial cells are packed around neurons, making up 50x more of the cells in your brain than neurons comprise [4]. So more and more labs are starting to investigate the billions of other cells in the brain.

Figure 3. There are many cells in your nervous system that work in tandem with neurons. Two of these glial cells are called oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells. They are involved in the fatty myelination process. Source: Bruce Blaus, Wikimedia commons

One of those other cell types is called the oligodendrocyte, which wraps around neuron axons in the central nervous system to form myelin. Schwann cells are another cell type that perform the same function but in the peripheral nervous system. These cells create the myelin cover for neurons, without which you would process information much slower. Although neurons have been in the spotlight for years, your brain would be much less impressive without the added speed from glial cells.

Figure 4. We are looking down on a brain from above. The top of the figure is where the face of the animal would be. The right hemisphere is sliced open so you can see the white matter on the inside of the brain, surrounded by grey matter. Source: Pikrepo

Now this has been a very zoomed in picture of the goings-on in your brain. But take a moment to think about the brain as a whole. It’s filled with billions and billions of cells. You might not expect that they cluster together to form color patterning, but they do, and it all comes back to fat. White matter is full of myelinated axons. It’s called white matter because this tissue in your brain is lighter in color than the darker grey matter. Since white matter is full of myelin, it has much more fat than grey matter. Fat is lighter in color than the rest of your brain material, producing regions of lighter tissue in more fatty concentrated areas. It makes sense that white matter is in the middle of the brain, so that axons can take the most direct path to the next neuron, rather than traveling around the brain’s circumference.

All of this is to say that fat does some great things for your mind. You might not have realized that your brain is a giant ball of fat. So next time you’re eating ice cream, just hope it goes straight to your brain.

(Disclaimer: I don’t think a fatty diet actually aids myelination in your brain, but it would be great if it did.)

References:

[1] Morell P, Quarles RH. The Myelin Sheath. In: Siegel GJ, Agranoff BW, Albers RW, et al., editors. Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. 6th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven (1999).

[2] UCSB ScienceLine. How fast do nerves send signals to and from the brain? (2009).

[3] Cavanagh J.B. The Problems of Neurons with Long Axons. (1984) The Lancet 323(8389):1284-1287.

[4] Kandel E., Schwartz J.H., Jessell T. Principles of Neural Science. (1981).

More From Thats Life [Science]

- CRISPR technology may be a promising tool to combat multidrug resistant fungus C. auris

- How the search for a universal gene forever changed biology: the story of Carl Woese and 16S sequencing

- Quarantine Blues? The Effects of Social Isolation in the Brain

- The Lovebug Effect

- CRISPR: Careful When Running with Genetic Scissors

- More ›