Josh Foster HOW IT WORKS

virus foodborne public health covid-19 communication

Interview with Dr. Matthew Moore - Viral Perspectives

I’m here with Dr. Matthew Moore, assistant professor in the Department of Food Science here at UMass. He studies food safety microbiology with a focus on foodborne viruses, the aspects of which can be translated into advice and considerations for Covid-19. We wanted to hear his perspective on the coronavirus pandemic, the impact of viruses in society more broadly, as well as just hearing about some interesting science in general!

Note: this interview was conducted June 2020 and has been edited for length and clarity.

-Bold text: Myself, Joshua Foster

-Regular text: Interviewee, Dr. Matthew Moore

Can you give me a brief walkthrough of your career?

Yeah, of course. I originally did my undergrad at Cornell in food science where I did research under the guidance of Dr. Kathryn Boor; I’ve been [in] food science the entire way.

From there I went straight into getting a PhD in food science at North Carolina State under Dr. Lee-Ann Jaykus who does virology research. While I was there, I kind of had my hand in a lot of pots. I did work on inactivation, looking at disinfection of norovirus (which is more difficult than SARS-CoV-2), all the way to detection, especially focused on environmental and food viruses. The whole sample preparation end of things is something people tend to forget; it’s one thing to be dealing with clinical samples, where you have a virus at a relatively high concentration, whereas it’s another thing if you’ve got this big 25 gram complex sample of food and you only have a few viruses. So you have to very specifically find a way to pick those viruses out and detect them. A lot of these principles have carried over to what we do in our lab.

Before getting here (UMass), I took a kind of left turn to work at the CDC for about a year to do work on antimicrobial resistance. After that I came to UMass, where our lab primarily does work in applied and environmental virology - what I’ve traditionally been calling food and environmental virology. So, looking at norovirus, hepatitis A - things like that - and a lot of the applied aspects. How can we better structure inactivation agents to kill these viruses? Because norovirus, and a lot of these non-enveloped viruses, they’re a lot tougher than SARS-CoV-2 and so they’re a lot harder to kill. One of the things our lab is doing is trying to further tease out the specific broader principles of formulating agents against these types of viruses, so that you could take any inactivation agent that’s even a “mediocre kill” and then kick it up to the type of kill you’re trying to obtain. That’s the applied area, the inactivation, sample preparation, and detection.

Awesome, that was a great introduction!

Moving into some questions: I often hear different terms like “infectious”, “contagious”, and “transmissible” which have kind of been used interchangeably, do those terms have more explicit definitions? Or is it just colloquial preference?

People often interchange them colloquially. I think the biggest distinction to be made is between infectious virus and viral RNA. Just the presence of viral RNA does not mean there is an infectious virus. That’s actually something I spent a portion of my PhD doing - trying to find (outside tissue culture) molecular ways to better infer if you have actually infectious viruses.

That’s something I would like people to understand, the significance of swabbing and finding RNA fourteen days after people left the cruise ship [link]- that doesn’t mean there was still an infectious virus. Especially with SARS-CoV-2, where you have an associated protein-nucleocapsid (the protein shell that contains the virus’s genetic material), my suspicion (though not confirmed) is that the nucleocapsid helps stabilize it in the environment to some degree. And so, you’re potentially seeing a huge difference between the number of days people are detecting viral RNA versus when people have done infectivity assays in which you see the virus dies much sooner.

You’ve previously mentioned what has been described in the media as the ‘viral envelope’ of SARS-CoV-2. Could you describe the broad structural elements of that, and not necessarily the features that are unique to coronavirus? And what is the origin of the envelope? I’ve written about this a little for another post on TLS [Why Wash your Hands?], talking about how soap works and why to wash your hands but didn’t get into much detail. The crux was that it was host-derived membrane, as a broad stroke.

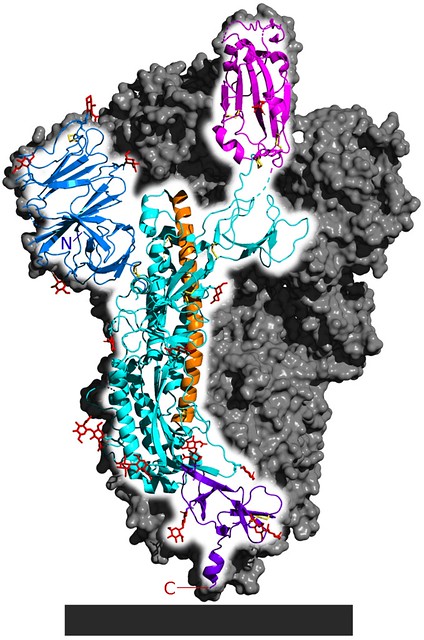

Yeah, well that’s basically it. The other consideration there, very specifically for SARS-CoV-2, there’s something called the spike protein, which is the viral protein involved in receptor binding, binding to the ACE2 receptor (A cell-surface protein receptor that the virus binds to get into the cell).

Fig. 1 Cryo-EM structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, the structure responsible for the interaction between the virus and its target receptor ACE2. [Source 5-HT2AR on Wikimedia Commons]

Are there host-factors that are carried into the viral envelope? Like some of the other host cell-surface receptors? Or, looking at it the other way, how pure is the lipid composition of the envelope?

I don’t know, that’s a great question. Really, from the applied end, whenever you have that lipid envelope it’s just easier to kill.

And that’s because it’s much easier to disrupt that envelope than it is to disrupt the protein capsid?

*Reminder, the protein capsid is the ‘shell’ that protects the viral genome from outside factors; it is made up of multiple interconnected proteins.

Yeah, exactly. But the earlier point is a good question, especially when you start looking at antigenicity (the ability of a molecule to induce an immune response), and what antigenic factors might be involved. It’s presumably just the spike protein but we’re not entirely sure. There’s another interesting point raised there, you hear people talking about different “strains” of virus but really they’re just detecting different variants. You’d need to actually see some mechanistic or novel physical difference that’s functional to really consider it significant. We are seeing different variants - genetic variants. Whether or not that translates to different strains of virus than can be potentially antigenic is a different question.

So, this is more of a SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) kind of mechanism? Each ‘variant’ is being defined based on maybe a couple of nucleotide differences?

Yeah, and that’s the thing, RNA viruses as a rule of thumb are generally error prone. This one [SARS-CoV-2] does have a proof-reading enzyme that helps to some degree, but when you have a 30kb genome of RNA, that replication is generally inaccurate. RNA-dependent RNA polymerases typically don’t have proof-reading, so a lot of RNA viruses are inherently, as a part of their evolutionary mechanism, prone to mutation. Much like norovirus or influenza. This one is maybe a little more stable, because I don’t think you can have a virus with a genome that big without having some sort of proof-reading element. So, the probability you’re going to see variants throughout a pandemic is not unexpected. The big reason we want to keep an eye on that is specifically for vaccines, as well as protective immunity. We still have the question of “How long is protective immunity?” At this point it seems like people are generating antibodies that are for the most part neutralizing, but how long that lasts we don’t know.

Always something else to keep in mind. We were talking about the envelope earlier and how that’s kind of associated with instability of the virus; what attributes are causing the virus to decay in and of itself? Is this just entropic breakdown of the lipid envelope once it gets outside the appropriate aqueous environment?

Yup! When you’re thinking about using inactivation agents, in addition to hand soap, many of them will disrupt that lipid envelope and once you do that it’s rendered non-infectious. So that’s why they’re [enveloped viruses] a little bit easier to kill, they’re a little bit more, delicate I guess. In the environment it’s not going to hold up like a virus like norovirus. Whereas norovirus is one of those ‘tried and true’, where a notable portion of transmission can be environmental. Its capsid is literally one protein that self-assembles into a super stable capsid that’s evolved to be resistant to stomach acid and digestive enzymes, things like that.

Is there any impact of material on the longevity of the particles?

Oh yeah. Absolutely. Not only in how long it survives on those surfaces, as there have been differences even for SARS-CoV-2 identified, but also the transfer. So, if you’re thinking about environmental transmission, transfer efficiency is something of great interest. As a general rule of thumb, in terms of transfer the virus will tend to persist longer in cloth, and sort of porous surfaces, but the transfer will be worse. Say there is a virus deposited on say a cotton t-shirt or something like that, it may survive a little bit longer but the actual transfer, and ability to transfer to something like your hand, is not as efficient. Because you can imagine it’s hiding in all the crevices…

It can permeate any small holes but the converse is true and it takes just as long to make it back out.

Yeah, whereas your transfer is going to be a lot more efficient if it’s on something like stainless steel. That said, we have done some work with norovirus and people have looked at other viruses and found some surfaces out there called self-sanitizing surfaces. Copper is one of them. There have been some pretty cool studies, not just for viruses but for bacteria as well. In hospital settings, people will sort of guild the outside of common touch surfaces with copper, or some sort of copper alloy, and they’ve actually reduced transmission.

Oh interesting, that’s an extremely useful finding.

Yeah, and since SARS-Cov-2 is pretty easy to kill, relatively easy to kill compared to norovirus, and copper worked on norovirus to an OK degree it has been relatively effective. I think it died in a couple hours, maybe six hours, I can send you a paper where they actually looked at survival on different surfaces.

That’d be super! [Links here & here [2-3]]

Branching off the discussion of how material can affect transmissibility, are their other significant factors, biotic or abiotic, that are worth considering in that same realm?

Oh that’s a great question, I kind of had that thought myself. Usually, bacteria aren’t high environmentally on a lot of surfaces, they are there, but to what degree they may play a role in SARS-CoV-2 infection I don’t know. But it’s an interesting thing to think about.

One thing to definitely think about though is organic load. When we’re talking about trying to disinfect surfaces to make sure the virus doesn’t transmit if there’s a high amount of junk/dirt on that surface, and you don’t clean it off, you’re not really going to get to the virus. So, whatever chemical disinfectant you’re spraying, most of it may be used up interacting with all these other organic materials. If you think about it, bleach, which isn’t specific, it’s not just going to react with the virus but with everything organic, so it reduces the efficacy. So that’s always a consideration when you’re talking about disinfection.

There’s been some indication that SARS-CoV-2 may persist long-term in the population, potentially similar to something like the flu. If a vaccine is developed would the long-term persistence of the virus, and potentially high error rate, suggest that the vaccine would need to be reformulated with some regularity, in the same vein the flu vaccine is?

That’s a good question which sort of gets back to what we were discussing earlier in terms of “Is there a phenotypic relevance to the variation we’ve observed?”. I don’t know, I think it’s still too early to really tell that. And if it does end up persisting, does it end up mutating to the point it ends up attenuating itself, and just becomes more like another common cold, I don’t know. I don’t know if we know enough to make a conclusion. The hope would be we would get a vaccine [4], and this is the key part, and get enough people actually getting the vaccine that it ends up just fizzling out with herd immunity. Because there’s always a new vulnerable population being born, who need to be protected with herd immunity.

Yes exactly! But we can only wait and see… We’ve been talking about the fundamental biology, or at least the structural aspects of the virus, but I’d like to move into the detection realm here. It’s my understanding there are two main strategies we’re looking at for detecting the virus currently. The nucleic acid detection you’ve mentioned earlier and serum tests like ELISA that look at the antibodies. Are there any others that have been commonly used? What are some potential advantages/disadvantages of each that are worth considering?

So, if you’re going to broadly lump them together in terms of what’s being used, currently it’s going to be either targeting nucleic acid or targeting antibodies. They’re going to tell you different things, so we need both.

Largely for techniques it’s mostly just RT-qPCR for nucleic acid testing and for antibodies it’s just some form of an immunoassay, like an ELISA. In terms of the advantages and disadvantages, certainly and I think it’s been reported that you’re seeing a pretty good number of false negatives. Whether or not that’s something to do with the actual physical sampling process (just not picking up enough virus) or its inherent to the technique itself that’s certainly a negative for RT-qPCR. There’s also been reports of high false negative and positive rates with some of the antibody tests, or at least there were in the initial stages. Because there’s a little bit less regulation there it was kind of almost like the wild west with a lot of companies just producing all these and not really validating them.

Getting into the idea of transmissibility and infectivity, there’s been a lot of discussion into infection by asymptomatic carriers, is that of any particular emphasis with SARS-CoV-2? Or how does this virus compare to other respiratory viruses in that same way?

I’m not as much of an expert on that, not enough to comment necessarily. WHO did have a press conference, I think it was in the news the other day, in which they said asymptomatic transmission was rare. But I don’t know what evidence they’re basing that on. I would suspect that it is actually playing a role, so I don’t know what evidence WHO had to make that conclusion. Or, if what they’re referring to is its mostly mildly symptomatic people that are transmitting the virus. [Clarification link 5]

Here’s a question I overlooked earlier, going way back to disinfection, is UV sterilization effective against viruses?

Depends on the virus.

Is that getting into more structural aspects? Or is the capability of UV to disrupt the virus even further delineated than that?

It can be both. UV light can destroy the genetic material, and there’s some evidence it can disrupt some proteins, but I’m uncertain of the exact effect on the lipids. I would presume it would oxidize them but I’m not sure. I don’t think I’ve seen data for SARS-CoV-2, but I’m sure there is data on other coronaviruses I could look up. I would assume it would be pretty effective against SARS-CoV-2 at least.

Would that be because of its ‘weaker’ lipid envelope? Whereas a protein capsid virus would not be as susceptible?

Well, for some of the non-enveloped viruses UV can be fairly effective. But the big challenge with UV sterilization is actually getting to the virus. So, if there’s a lot of crevasses, or if it’s an opaque material, and the virus is sort of hidden below the UV isn’t going to penetrate and kill.

So UV is great on a nonporous, perfectly flat surface…

Yes, and even surfaces that seem flat have a bunch of micro-imperfections which can be troublesome. But in general it’s fairly good! I wouldn’t entirely rely on UV but it’s good to have.

I keep seeing these advertisements for the UV sterilizers for your phone or the wand or whatever and I had, I don’t know if apprehension is the right word, but I know you need like 30 minutes of exposure to be effective. So, I was wondering how effective something like the wand could be.

Oh that’s a great point, that’s the other aspect of inactivation, it’s not just organic load it’s also contact time. You need adequate exposure to the inactivation method. So, it certainly doesn’t hurt but…

An excellent point. Moving forward, I wanted to touch on something interesting you brought up during the Life Science Café [The Pandemic That Changed The World: Many Questions and a Few Answers]. You mentioned that prepared food is relatively safe because the natural route of infection for the virus is through the respiratory tract, so the viral particles aren’t as likely to survive and infect you through the gastrointestinal tract. Now, just for the sake of an example, say instead of incidental exposure someone sneezed directly on your food. Is the lowered risk of infection through food just based on the viral load, or would it be low across the board?

So, with any type of infectious disease there’s never a 0% chance, it’s always some probability. From what we’ve seen with studies of MERS you’d need to ingest a fairly high load of virus, one that’s not normally present when it’s just exposure from a food handler depositing the virus through contact. Presumably that low titer would just get eaten up in your stomach acid, and in terms of food-borne normally there’s very low number of viral particles on the food [sic]. So to have a scenario that mimics what was seen with MERS you would need more virus to be deposited than is likely to occur. But we can’t necessarily say as we don’t have the data for SARS-Cov-2 yet. It wouldn’t be realistic in terms of food borne at least in the way that we know viruses are transmitted. The stomach acid really just does a number of these viruses, because that’s not how they evolved.

Well that was all of the questions I had, thank you so much for taking the time and answering everything. You’ve given me a lot of great information that I’m looking forward to sharing with the TLS community.

References

[1] Feuer, W. (2020, March 28). CDC says coronavirus RNA found in Princess Cruise ship cabins up to 17 days after passengers left. Retrieved September 01, 2020, from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/23/cdc-coronavirus-survived-in-princess-cruise-cabins-up-to-17-days-after-passengers-left.html

[2] Kampf, Günter, et al. “Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents.” Journal of Hospital Infection 104.3 (2020): 246-251.

[3] Van Doremalen, Neeltje, et al. “Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1.” New England Journal of Medicine 382.16 (2020): 1564-1567.

[4] Cimons, M. (2020, June 10). SARS-CoV-2 is mutating slowly, and that’s a good thing. Retrieved September 01, 2020, from https://hub.jhu.edu/2020/06/10/sars-cov-2-dna-suggests-single-vaccine-will-be-effective/

[5] Sullivan, P. (2020, June 09). WHO seeks to clarify widely criticized statement on asymptomatic spread. Retrieved September 01, 2020, from https://thehill.com/homenews/coronavirus-report/501813-who-seeks-to-clarify-widely-criticized-statement-on-asymptomatic?fbclid=IwAR3evsRuZbo2RWV9bgXESwwD7IfE3Y_NGlh3vR9vxKQGljXgcKHJet3mmZ8

More From Thats Life [Science]

- CRISPR technology may be a promising tool to combat multidrug resistant fungus C. auris

- How the search for a universal gene forever changed biology: the story of Carl Woese and 16S sequencing

- Quarantine Blues? The Effects of Social Isolation in the Brain

- The Lovebug Effect

- CRISPR: Careful When Running with Genetic Scissors

- More ›