Emma Dauster HOW IT WORKS

adaptation animal behavior neuroscience navigation

Going on Autopilot? Thank Your Place Cells

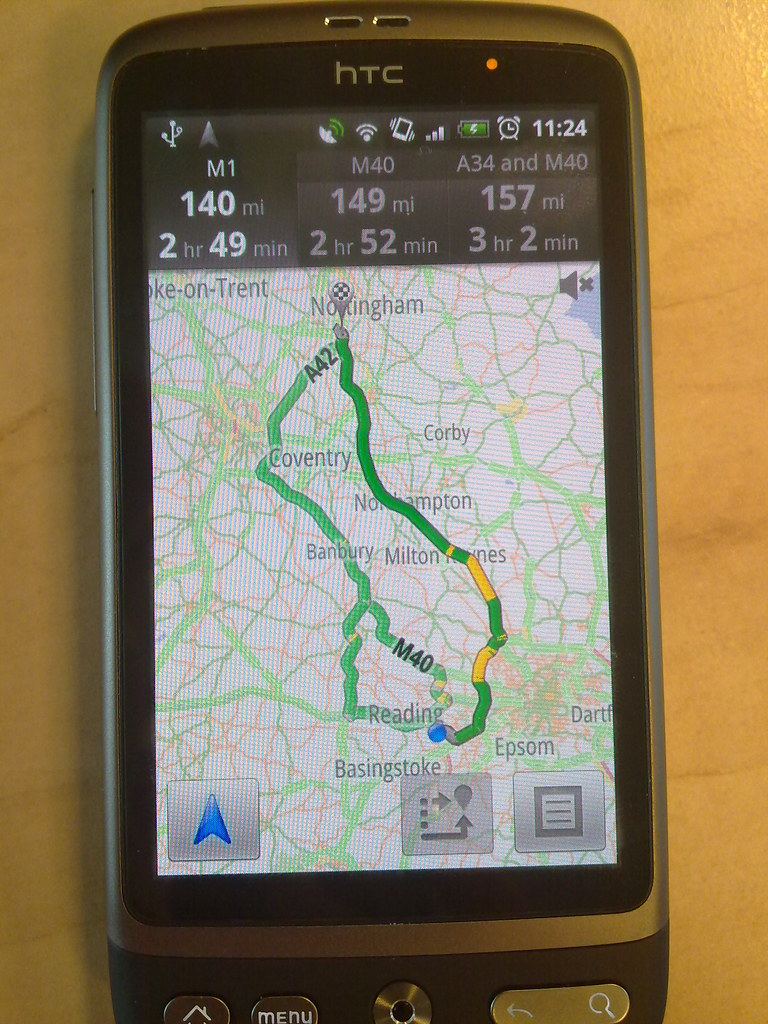

Figure 1. For the most part, we navigate through our daily routines without using external mapping assistance. Turns out that our brains have their own mapping system. (Source: Flickr, David Carrington)

Odds are you have a daily commute and follow the same route to work every day. Maybe you stop by the same coffee shop on your way to work. You probably had to concentrate on where you were going when you first started this job. You likely started your commute noticing every establishment you passed and taking note of every landmark along the way. That might even be how you found that go-to morning coffee shop. But now that you’ve been working there for a while, you don’t notice every store that you pass. You can even feel yourself slip into autopilot heading down the street and stopping into the coffee shop, then heading on your way to work. A lot of people experience this shift, from alert and aware of new surroundings, to knowing the way around so well that you don’t even remember getting yourself to work. Somehow, you’re sitting there with your coffee so you must have gone along your usual route. This phenomenon is something you are aware of, but you might not know that it stems from the neurons in your brain and how active and interconnected they are.

There are specific cells in your brain called place cells that become active when you are orienting yourself around a new environment [1]. When you go down a specific road, a group of cells produce action potentials. When you turn the corner, other cells burst with action potentials. When you get to another straight away, the third group of cells produce action potentials [2]. These are specific cells that hone into specific places along your commute, hence the appropriately named “place cells.” When you are in a location that you’ve never been in before, your place cells are super active. They are producing tons of action potentials and dividing themselves up along the path that you are traveling. Ultimately, only a small group of place cells is associated with a portion of that path [2].

Figure 2. A rat in this figure is traveling down a path. Different populations of cells become active as the rat approaches different stretches of the maze, as denoted here by color code. (Source: Wikimedia commons, Stuartlayton)

Once you’re familiar with a route, these place cells become linked by strong connections. They don’t have to form new connections every time you travel the familiar path, but rather utilize those already created [2]. Place cells act in a well characterized manner as described by the common saying in neuroscience, “cells that fire together wire together.” It is easier for your brain to use the already established connections than to create new ones. Since you know where you’re going, it is adaptive for your brain to not work as hard as it did when this environment was novel. You can now spend your time thinking about that project you need to get off the ground instead of devoting your attention to which turn is coming up along your path.

Figure 3. This is a much larger scale of the “cells that fire together wire together” phenomenon. Scientists can determine which cells send information to which other cells, and then create a map of cellular communication throughout the brain like the maps above. (Source: Wikipedia, J.menezes1204)

One day, you are on your way to work and your regular coffee shop has closed. You know that you can’t go there to get your coffee in the mornings anymore, but somehow you still end up on autopilot in their parking lot some days. Now you need to re-route and find a new path that doesn’t lead you to a closed establishment. Your place cells are springing to life! If the path changes, your previously subdued place cells that were not utilized in the old path will jump in to make a representation of your new path. Eventually, the new route will become familiar and the new connections will solidify. You and your neurons are back to autopilot.

Even cooler, since there are so many cells packed into your hippocampus (the part of the brain largely devoted to memory where place cells reside) you do not need to change the mapping that you had previously established to create a new route representation in your brain. The place cells that mapped onto your old route will stay inactive as you go along the new route. A different subset of place cells, or the same cells forming connections with new cells, create a map of your new route [2]. If you find yourself returning to your hometown and following the same path you used to take years ago, it’s because the development of new spatial representations in your brain does not seem to affect the old representations. It is simply more of your cells being utilized in additional novel ways for new environments.

So don’t worry about running out of space in your brain for new memories. At least as far as navigating a new environment goes, you can develop new memories without having to replace the old ones. All of these brain maps will help you to be more productive with your time and cognitive resources.

References:

[1] O’Keefe J, Dostrovsky J, 1971. The hippocampus as a spatial map. Preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely-moving rat. Brain Res. 34:171-75.

[2] Wilson MA, McNaughton BL. 1993. Dynamics of the hippocampal ensemble code for space. Science 261:1055-58.

[3] Moser EI, Kropff E, and Moser MB. 2008. Place Cells, Grid Cells, and the Brain’s Spatial Representation System. Annual Review of Neuroscience 31:69-89.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- CRISPR technology may be a promising tool to combat multidrug resistant fungus C. auris

- How the search for a universal gene forever changed biology: the story of Carl Woese and 16S sequencing

- Quarantine Blues? The Effects of Social Isolation in the Brain

- The Lovebug Effect

- CRISPR: Careful When Running with Genetic Scissors

- More ›