Rachel Bell EARTH'S ORGANISMS

evolution primate apes morphology

Why Don't Apes Have Tails?

Take a moment to think about your favorite animals. From lizards to songbirds, squirrels to monkeys, they probably all have tails. These appendages have been adapted to serve a variety of functions, just at a glance: they allow fish to move through water, help cats balance, can alert other deer to the presence of a predator, and in possums and some monkeys act as a fifth limb to hold onto tree branches [1]. Tails are almost ubiquitous throughout the animal kingdom, yet all apes—the superfamily that includes gibbons, orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans—lack an external tail! Why would tail loss occur in an entire group of animals when it seems so useful? To answer this question, we have to dive into the evolutionary history of apes.

Figure 1. This wooly spider monkey is one primate species whose tail has evolved to be prehensile, meaning that the tail is capable of grasping and holding objects like a hand. This is very useful when moving quickly high up in the trees! Photo credit: Paulo B. Chaves via Wikimedia Commons.

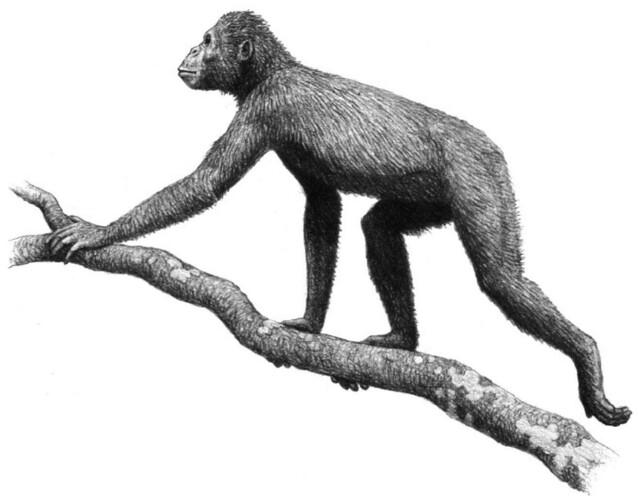

Because all living apes and apes in the fossil record lack tails, scientists think it is safe to say that all apes—living and extinct—are tailless [2]. The ape fossil record suggests that the ape lineage evolved taillessness by ~20 million years ago [3]. The earliest known ancestor to apes, Proconsul heseloni, lacked an external tail based on fossil evidence [2]. The last sacral vertebra on Proconsul was tapered, indicating that a tail couldn’t have attached to it [4]. Indeed, while many fossil apes from 19-15 million years ago had some physical features that were more like living monkeys, they all lacked a tail [5]. Despite the presence of some classic monkey-like features in these fossil apes, the key to understanding why apes lost their tails is that tail loss didn’t happen on its own—it actually evolved within a suite of other physical traits, heralding a major change in how these animals moved and interacted with their environments.

Figure 2. Proconsul africanus, often considered one of the earliest apes. Image credit: Mauricio Anton via Wikimedia Commons.

So, why would losing our tails be beneficial?

Earlier research on the topic suggested that tail loss co-evolved with orthogrady, defined as upright posture with independent movement of hind limbs and forelimbs [6]. However, many early fossil apes who lacked tails still exhibited horizontal posture with use of all four limbs in parallel motion to move throughout their environments—a positional behavior known as pronogrady [5]. The universality of orthogrady in apes appears to have evolved later (and separately) from tail loss. For example, the earliest known upright fossil ape in Europe was from 12 million years ago, which is at least 6 million years after tail loss occurred [5].

Some researchers suggest that taillessness co-occurred with an increase in body size, which would make having a tail impractical [2,3,7]. Many monkey species use their tails to stabilize and balance while quickly climbing and leaping across trees. Yet some ancestral ape species are estimated to have weighed up to 110 pounds [2], so any tail large enough to confer a stabilizing benefit might not have been evolutionarily “worth it.” Instead, these large fossil apes may have compensated behaviorally and physiologically, via slower, careful grasping movements and increased limb mobility as they navigated across branches [2,3]. This co-occurrence of external tail loss and a more deliberate grasping style of locomotion has also been observed within sloths, as well as a distantly related group of nocturnal, non-ape primates known as lorises [2,7].

Figure 3. A Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelli) demonstrating his large body size, excellent branch-grasping abilities, and lack of a tail. Photo credit: Arifinal0109 via Wikimedia Commons.

Researchers are continuing to explore how and why apes are tailless, so it is possible that our current understanding of adaptive tail loss will change. However it happened, it is clear that losing our tails coincided with, and even preceded, other huge physical shifts that defined the evolutionary trajectory of apes, including humans. If early apes had never lost their tails or changed the way they moved, would upright posture or walking on our hind limbs have happened? We can’t be sure, but we can appreciate that we evolved the way we did. Or, then again, maybe you wish you had a tail!

References:

[1] Sally Cragin. A Tale of Tails: Why Do Animals Have Them (and Why Don’t We)? AP News. (November 2018).

[2] Scott A. Williams and Gabrielle A. Russo. Evolution of the Hominoid Vertebral Column:

The Long and the Short of It. Evolutionary Anthropology 24:15-32 (2015).

[3] Hunt, Kevin D. “Why are there apes? Evidence for the co‐evolution of ape and monkey ecomorphology.” Journal of Anatomy 228, no. 4 (2016): 630-685.

[4] When Humans Lost Their Tails. Your Inner Fish, PBS Learning Media. (2014).

[5] Nakatsukasa, Masato. “Miocene ape spinal morphology: the evolution of orthogrady.” In Spinal Evolution, pp. 73-96. Springer (2019).

[6] Keith, Arthur. “The extent to which the posterior segments of the body have been transmuted and suppressed in the evolution of man and allied primates.“ Journal of Anatomy and Physiology 37, no. Pt 1 (1902): 18.

[7] Mincer, Sarah T., and Gabrielle A. Russo. “Substrate use drives the macroevolution of mammalian tail length diversity.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B 287, no. 1920 (2020): 20192885.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- Freshwater Mussels are Declining: Why Should You Care, and What Can You Do?

- The Story of Chestnuts in North America: How a Forest Giant Disappeared from American Forests and Culture

- Friendships, Betrayals, and Reputations in the Animal Kingdom

- Why Don't Apes Have Tails?

- Giant Bacteria, Giant Genomes

- More ›