Emma Dauster HOW IT WORKS

neurons pain axons biology

Bang! 'Ouch' *Grab*

You’re walking into a room and bang! You hit your elbow on a table. You exclaim “Ouch” and grab your elbow. Why did you feel the need to touch your elbow? You had just experienced pain from a touch to the elbow, so why would your next response be to touch it more? And why did it make you feel better?

Figure 1. Something inside you tells you to grab your elbow after you bang it on a table. What might this be, and why? source: pxfuel

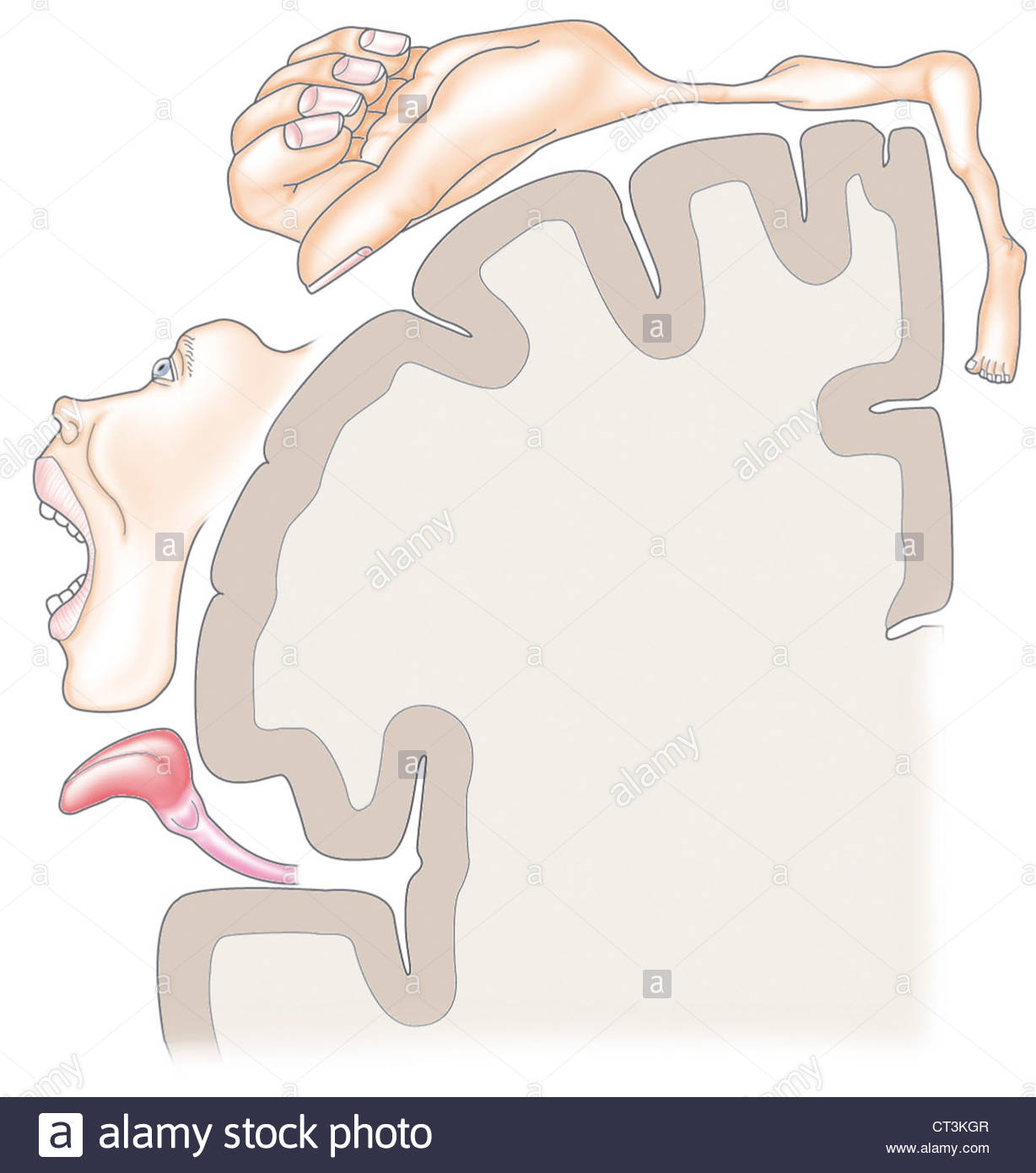

Pain is conveyed to your brain through nociceptors, or pain receptors, that are present under your skin and in your muscles. They are a sub-classification of receptors sensitive to touch, also known as somatosensory receptors. Touch signals come from all over the body, but most of these receptors are on your hands, feet, and mouth [1]. Because these regions are super sensitive to touch, their representation takes up way more brain space than touch signals from the rest of your body [Figure 2].

Figure 2. This is a section of the brain that represents sensory information. The cartoon representation of which part of the body sends information to which part of this brain section is called a homunculus. The information gathered from sensory neurons on different parts of your body is processed in the brain, and you can see that the hands, feet, and mouth are larger cartoons because they are processed by larger areas in the brain. Source: Alamy stock photo, BSIP SA

Fun at-home science experiment to demonstrate this point: Ask your roommate/parent/sibling to close their eyes. Take a pencil and lightly touch their fingertip. Move 1cm down and touch the same finger. Keep moving 1cm away until they can tell that you’re touching a different location on their finger. Now try the same thing on the back of their arm where the triceps are. Compare how far you can get from the original spot on the finger vs how far you can get from the original spot on the triceps before they can tell that the pencil tip is touching a new location. Spoiler alert: you can probably go farther away from the original touch point on the triceps than on the finger because there are way more touch receptors on the finger.

But let’s get back to your hurt elbow. First there’s a sharp pain. Then, after one or two seconds, a dull throbbing pain usually comes to your attention. This first and second wave of pain are due to minor differences in the fibers that bring information from the body to your brain [2,3]. The first sharp pain comes from a myelinated (insulated) fiber, which sends the pain signal to your brain faster than the second, unmyelinated, dull pain fiber. See this post for more information on the effects of myelination on the speed of information relays. The fast pain signal can travel up to 30 meters per second, while the second wave of pain only travels 1 meter per second [1]. You need both types of signals. When you’re in a dangerous situation you need to first realize that you’re in a dangerous situation so you can quickly remove yourself and stop causing harm to your body. Second, you need a dull pain that lasts longer and comes on later to remind you not to cause any further damage to that area while it is sensitive and healing.

So how does that bump to the elbow travel all the way to your brain? Well, the receptors for pain are just under your skin, but the cell bodies attached to those receptors are actually located in your spinal cord. Imagine a cell in the spinal cord and reaching out their fiber to access parts of the body, such as under the skin on your elbow where you are likely to experience disruptions due to external stimuli like hitting a table. The pain signal travels from your elbow to your spinal cord. The same cell that reached a fiber or two to the elbow usually reaches another (axon) all the way up the spinal cord and into a part of the brain called the thalamus. The thalamus processes sensory information from all five sensory systems (touch, sight, smell, hearing, and taste).

Note: The sense of smell is the only one that does not go directly to the thalamus, but the information eventually gets there.

Figure 3. This is a representation of what your spinal cord looks like in your body. Those branches coming out from the spinal cord are the peripheral nervous system. One of the main jobs of the peripheral nervous system is relaying sensory information, as described in this article. Source: Bruce Blaus, Wikimedia commons

The answer to the question at the beginning of this article comes at the level of the spinal cord. Some of the cells that receive pain information in your spinal cord can also receive information about non-painful stimuli in your environment. They are called wide-dynamic-range neurons (yes, there are neurons in the rest of the body too, not just the brain); they get information about sensations such as a breeze on your skin or a light touch that shouldn’t hurt. This might be a reason that you grab your elbow after you bang it on the table. The touch signal goes to the same neuron that the pain signal goes to so reaching for your elbow could be distracting your brain from pain. In other words, initiating the second wave of pain by clutching your arm can suppress the first wave and lead to a smaller pain response [4].

Figure 4. This is a drawing of a cross section of the spinal cord shown in Figure 3. Here, you can see the axons going up or down the spinal cord. Source: Villiger, Emil, Piersol, George A. (1912) Brain and spinal cord; a manual for the study of the morphology and fibre-tracts of the central nervous system

Next time you injure yourself, you can distract your brain from the pain in two ways:

Touch the part of the body that just got hurt

Think about how cool your neuronal system is and marvel at the inner workings of your body.

For more lab discoveries and research guidance, check out my website @ emmadauster.com

References:

[1] Kandel E, Schwartz JH, Jessell T (1981) Principles of Neural Science.

[2] Fields H (1987) Pain. New York: McGraw-Hill.

[3] Perl ER (2007) Ideas about pain, a historical view. Nat Rev Neurosci 8:71-80.

[4] Melzak R, Wall PD (1965) Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science 150:971-9.

More From Thats Life [Science]

- CRISPR technology may be a promising tool to combat multidrug resistant fungus C. auris

- How the search for a universal gene forever changed biology: the story of Carl Woese and 16S sequencing

- Quarantine Blues? The Effects of Social Isolation in the Brain

- The Lovebug Effect

- CRISPR: Careful When Running with Genetic Scissors

- More ›